A Walk on the Dark Side from Rousseau to the Rolling Stones

When the Rolling Stones sang Sympathy for the Devil at the Altamount concert, and all hell broke loose

I started thinking about the song "Sympathy for the Devil" again in 2024 when I heard a Rolling Stones concert was scheduled for Santa Clara near where I live in San José. If you keep reading, I think you will probably come to agree with me that the context in which I first heard the Stones perform that song in person vividly illustrates the times that formed me and the errors from which I have been delivered.

To use a phrase common during the hippy movement when I was young, I’ve been through a lot of changes since the time I heard them play that song. I'm now 79, and Mick Jagger, the Stones' lead singer, is 82. At the time “Sympathy for the Devil” first became a hit in 1969, I was twenty-four. I had left the Catholic Church seven years earlier in adolescent hubris.

To quote the opening line of “Sympathy for the Devil,” “please allow me to introduce myself.”

In the Catholic schools I attended in Massachusetts for nine years during the 1950s, I had been a straight-A student. My doing well was not remarked upon, and I don’t remember being praised. I now believe that was a good approach for raising Catholics—because the saints tell us that humility is the first step to holiness. The only praise I remember was a second-hand compliment, when my two younger sisters complained that the sisters at school would say things like, “Why aren’t you as smart as your sister, Roseanne?”

My enforced humility was eroded after I came in first in a city-wide exam that won me a scholarship to Notre Dame Academy High School in Worcester. I had been rebelling against my widowed mother for three years by then, and my mother was glad to have that achievement of mine to brag about. But then my rebellion against school rules by smoking cigarettes in uniform on a city bus I took to school got me expelled at the end of my freshman year.

When I entered Leicester High School, the nearest public school to where my mother had bought a house in a more rural township called Cherry Valley the next fall, I got a lot of attention. Mr. Kelly, the guidance counselor, took me aside to tell me my scores on the Preliminary Scholastic Achievement Tests at the beginning of that year would qualify me for any college in the country. I soon left Leicester High partway through my sophomore year for a long-term care hospital for scoliosis surgery, followed by a long recuperation. When I returned to school eleven weeks into what should have been my junior year, I impressed the teachers again. I aced the chemistry quiz at the end of the first week I was back by simply reading the eleven chapters I had missed the night before the quiz.

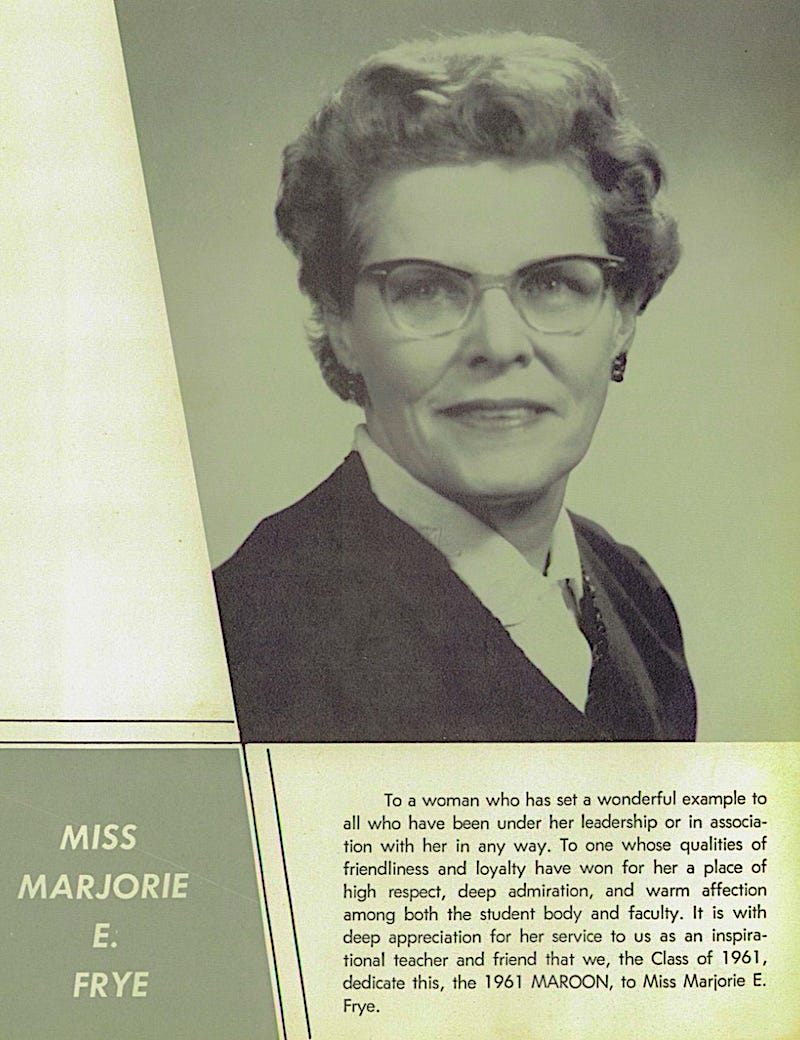

While I had been hospitalized, I had exchanged letters with my English teacher, a New England-born writer-manqué with a broad Maine accent, who had attended the Bread Loaf writers conference. Miss Marjorie E. Frye wore leg braces and walked with crutches because of childhood polio. She read my letters to the class.

Miss Frye encouraged me to write. She told me I could write the Great American Novel.

All that fed my adolescent ego, and from then on, becoming a famous writer became my goal in life, when I wasn't dreaming about being a famous artist.

As it turned out, I didn’t become famous either as a writer or artist, but my pride eventually led me to reject the Catholic Church.

Starting at the age of fifteen, during my year stay in the hospital, I devoured two or three books a week that Miss Frye sent me, plus many others that came my way. I read authors as varied as Tolstoy, Faulkner, Christie, Flaubert, and O’Connor. I think Miss Frye intended to help me learn how to become a good writer by encouraging my reading of a wide range of literature. Sad to say, while reading all those books, I also assimilated one underlying assumption of most modern writers—that one cannot be both a serious intellectual and a believer in Christianity. (Only later, when I read Flannery O’Connor’s essays, did I understand and admire her zealous Catholicism.)

I read but didn’t pay too much attention to the spiritual classics Miss Frye sent me by St. Augustine, Brother Lawrence of the Trinity, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. Ignatius of Loyola, because I was attracted to the more au courant, avant-garde ideas in the other books. Plus, I have to confess I was a curious teenager, and I was often looking for the “good parts,” which were the parts that were frank about the then-taboo subject of sex. I never did find anything explicit, but I absorbed a lot of attitudes that differed from Christian morality. I remember being frustrated once to find that Miss Frye had heavily inked out a few words in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, which I could not make out no matter how hard I tried.

Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was one significant influence away from my faith, because it describes the main character’s fall from being a fervent Catholic, tortured as I later learned Luther had been before his apostasy, by compulsive sexual sins he couldn’t stop engaging in, no matter what penances he inflicted on himself. Stephen Dedalus, also like Luther, ended up rejecting the Catholic Church. Dedalus signified his break with the Church when he made it clear to everyone around him that he would not perform his Easter duty, the duty of every Catholic to receive the Eucharist once a year.

Simone de Beauvoir‘s The Second Sex was another big and bad influence on me. As you may recall, the writings of de Beauvoir influenced the growth of feminism in the 1950s and beyond. The first wave of feminism focused on getting the vote and property rights for women. De Beauvoir and the rest of the second wave of feminists focused on changing sexual mores, which they claimed oppressed women.

De Beauvoir shared with existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, her intellectual partner, the conviction that for a woman to demand marriage before intercourse with a man was a form of prostitution.

I bought into the lie that people with religious beliefs who acted kindly to others were hypocritically acting out of self-interest, and that only the intelligentsia were truly good. Years later, de Beauvoir and Sartre dropped way down in my estimation after I found out they had an “open” relationship. They never married, and they had talked catily and condescendingly between themselves about the ever-changing string of lovers, oftentimes their students, whom they seduced with lies and sometimes passed between each other. Even though they were of the intelligentsia, they were despicable people. I learned through this and other examples that learning does not make people good, no more than superficial adherence to Catholic doctrine does.

Many times I thought about writing a book titled something like, Casualties of the Sexual Revolution, but I remembered that a Carmelite spiritual advisor once told me not to write it, since I’d have to be pondering the evil things I’d be writing about. I may be disobeying his advice by what I’m writing here, but since I started, I might as well finish. May God protect me and anyone who reads this, for my intention is to throw light on the hidden evils and not to praise these things.

The existentialists joined the Marxists, the Freudians, and other "philosophers" of sexual revolution, such as Hugh Hefner in his Playboy Philosophy, in preaching an anti-gospel that turned Catholic truth upside down. Belief in God is a crutch, morality is repressive and twists people's psyches, and marriage is slavery. Believers, they claimed, were too cowardly to face the existential reality that life is meaningless. I didn’t lose my faith right away, but seeds were planted.

After high school graduation, I became the first person I knew of on either side of my family who went to college. In another rebellious act, I scorned going to a Catholic college, and U Mass, Amherst, I thought, wasn’t important enough. I was too timid to apply for Radcliffe, the then-female-only branch of then-male-only Harvard.

I decided on Brandeis, which was founded after World War II and named after the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, Louis Brandeis. A mostly Jewish university would be a strange choice for a Catholic until you factor in the full scholarship they gave me. I was also attracted by an article in a major newsweekly magazine that listed Brandeis as one of the top ten U.S. universities that year. According to their admissions materials, Brandeis was open to all excellent students, Jewish or not. They wanted me, so that’s where I went.

Most of my fellow students were non-practicing Jews. I stopped practicing my religion, too, after about a month there. Rather cruelly, I thought, for us Catholics, the freshman cafeteria served my favorite food that we never had at home, rare roast beef, once a week—but only on Fridays. One Friday, I decided I was going to prove, like Stephen Dedalus, that I was liberated from Catholicism. I ate the roast beef.

That affected me like a drink of poisoned Kool-Aid. After I lost my faith, I lost my moral compass, and I ran head-on into the double standard. I got depressed, stopped going to classes, and I flunked out at the end of the year.

One ray of hope was that Brandeis sent me a letter telling me I could reapply in a year, and that if I got my grades up again, I could regain my scholarship.

The only work I could find back home after a summer of looking was as a file clerk for $1 an hour. The relatives who had been supporting me threw me out (that's a whole other story). So at eighteen years old, I was homeless, couch surfing around Harvard Square, continuing my search to find my “true people.”

Instead, I found that many of “the best minds of my generation”—to quote Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl, were stark, raving self-indulgent while preaching a philosophy of “whatever turns you on.” I read LSD guru Timothy Leary’s Journal of Psychedelic Studies, and I “tuned in, turned on,” although I never quite “dropped out.” When I saw Leary give a talk one night at Harvard after he was fired as a professor but was still wearing a suit, I had taken LSD and, in contrast to others of the audience who said they couldn’t understand what he was saying, I thought everything he said was cosmically profound.

I sampled just about everything that the early 1960s remnant of bohemian idealism had to offer in the way of alternative lifestyles and then jumped on the hippy bandwagon after the press began to tout it in the mid-1960s.

To my disappointment, the conversations were not nearly as intense and interesting as I hoped they’d be. The bohemians I met either weren't articulate or they were articulating objectionable or just plain crazy ideas.

Anyway, I found myself instead mostly surrounded by hippies, most of whom had what I called ten-word vocabularies: “Hey, man. How ya doing? Far out! Groovy! Outa sight.”

I began to scorn them as mostly inarticulate lemmings who were blindly pursuing a Rousseauian dream about harmony and understanding fueled by sex, drugs, and rock and roll. To my enduring great regret, we and others who followed did succeed in tearing down and rebuilding society, and in redefining morality, and the world today is a lot worse for what we helped bring into being.

After a while, I found two small rooms to rent in the South End of Boston for $25 a month. Then over the course of a year and a half, I somehow saved enough money to pay tuition for a semester, so I dropped back into Brandeis again. I got my scholarship back after the first semester.

Then I met and started living with “my old man,” George, in a funky apartment in an old brownstone in the South End of Boston near a clanking elevated train that ran a half a block away along Washington Street. George rented rooms to friends, and often when I made breakfast, someone would hand me a joint in the kitchen, and I’d lose my motivation to commute to Waltham for classes.

George loved road trips. I was inspired that Jack Kerouac had made a bestseller out of his inglorious beat Odyssey to Nowhere, On the Road. Maybe someday I could write about my travels. George had read several books on how to live on next to nothing. We followed the principles he learned in those books for months to save for a camping trip around the country.

During our four months of camping in an orange VW bus, when money ran short, we did short stints of agricultural labor. It was fun. We picked prune plums in Utah and black walnuts in northern California.

We arrived in San Francisco at the end of what the media was calling the Summer of Love. When we got to the Bay Area, we crashed with George’s open-minded, Methodist minister brother, Marv, and his family in Berkeley for a couple of months, then we found a place in the Haight Ashbury district, the hippy center of San Francisco.

My first impression when I got to San Francisco, as the song says, with flowers in my hair, was how little love there was. I pitied the straight fathers and mothers driving up and down Haight Street, hoping to catch sight of runaway teenage children among the hippy wannabes and opportunists who milled around the sidewalks.

That’s how it came about that I was a fallen-away 24-year-old lapsed Catholic living with my “old man” in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury district when I heard the Rolling Stones sing “Sympathy for the Devil” at the Altamont Free Concert in December of 1969. The song had hit the top of the charts and had been playing on the radio for months.

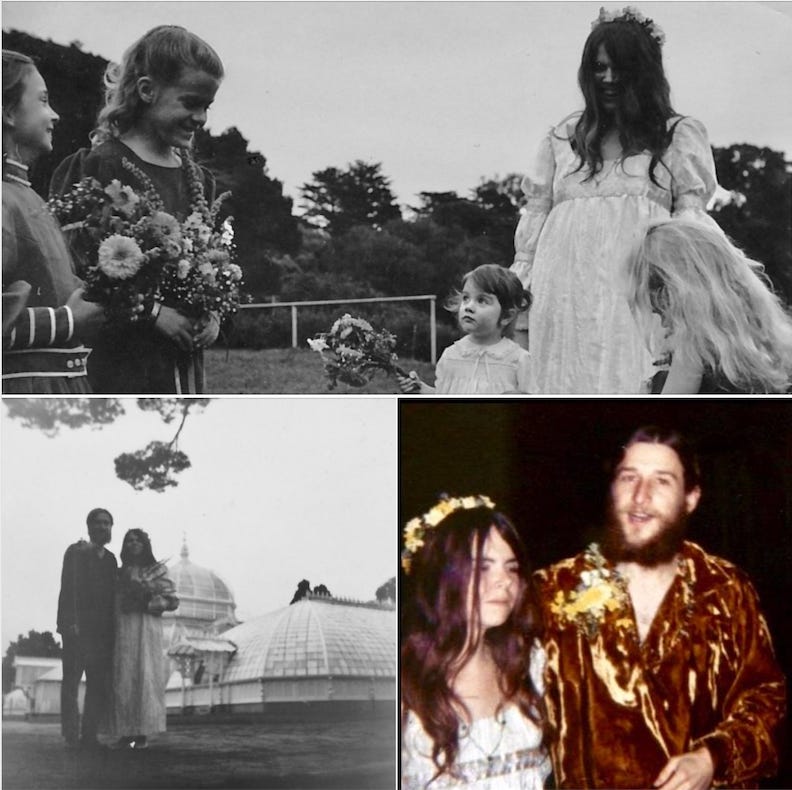

At the time of the concert, I was a few months pregnant with my first child. We weren’t married yet, because George was against it. He had been married once before.

George and I had lived together for over three years. He said we didn’t need to be married. We were already married, he said. After we agreed to have a baby together, and I conceived a child, he was willing to get married legally—for the sake of the child.

We originally loosely planned our wedding for Saturday, December 6, 1969, until we found out that a Rolling Stones concert was scheduled for the same date at the Altamont Speedway, less than an hour’s drive away.

We had envied those who had been able to be at the Woodstock concert four months earlier in New York state, and so George was willing to change our plans about an event as trivial in his mind as our wedding—for the chance to be at another major counter-cultural event. The press had painted a rosy picture of the era of Peace and Love supposed to have been ushered in by the stoned young people and their music in the mud and chaos at Woodstock. We hoped to get a piece of that peace, love, and rock and roll action for ourselves at Altamont.

We hadn’t planned a straight wedding with a church reserved and a reception at a rented hall anyway. We were planning to pick a spot on Mount Tamalpais in Marin County north across the Golden Gate Bridge, and gather there with our friends. George’s brother was going to perform the wedding ceremony for us.

I was friendly with George’s ex-wife, who had traveled with us partway to San Francisco with her second husband, their toddler daughter, and a friend in another van, until their van broke down, and they took a train without us the rest of the way. Our reception was going to be a potluck in the Haight-Ashbury apartment where George’s ex-wife and her current husband lived. So, we just casually let everyone know we’d moved the wedding date to the next week, December 13.

Early in the morning of December 6, we drove over the Altamont Pass in the VW bus of a friend of George’s, an artist of sorts who drew lewd sketches for the Berkeley Barb underground paper. Also along for the ride was his current “chick,” a younger Berkeley student.

Although the title of the song, “Sympathy for the Devil,” is disturbing to me now because I understand that it is dangerous to treat evil as a trivial matter, and although I am also ashamed about all the ways we blithely defied morals and conventions, back then, it all seemed cool.

Forgive us, Father, because we really didn’t know what we were doing. We didn’t have a clue about the reality of the powers of evil we were playing with.

The Stones thought they were just being hip and ironic by writing and performing a song that pretended the devil was a suave, well-mannered gentleman who was asking for a little sympathy. It was hip for all of us to pretend that nobody was damaged when couples formed without love and commitment and then broke up. And hip is what we wanted to be above all else.

The pose of pleading for sympathy for the devil reminds me of how we talked about astrology those days. You could entertain your friends by creating astrology charts and predicting their futures by their astrological signs, as George’s ex-wife often did, but we didn’t actually believe in it. We claimed we only believed in what was scientifically provable, and we smugly claimed we didn’t believe in anything we couldn’t perceive with our senses.

But we unabashedly contradicted ourselves, too, when we embraced the “spiritual” fads that came our way. G. K. Chesterton once put these words into the mouth of his detective, Fr. Brown, “It’s the first effect of not believing in God that you lose your common sense. After throwing away belief in God, many of us also threw away rationalism and skepticism, along with common sense.

One of the things we rather irrationally did was to turn to counterculture heroes, artists of all types, painters, sculptors, and protest singers as if they were prophets. We waited for each Bob Dylan or Beatles record to be released as the Greeks used to wait for their oracles, snapping up their albums when they came out so we could ponder the words and figure out what our modern-day prophets would tell us about what to believe and how to live.

The Rolling Stones were not in the prophet category. The Stones were only the most famous of the groups of young rock and rollers that had embraced the pounding sexual rhythms of the rhythm and blues musicians and their raunchy expressions of sexual matters. We thought all that was hip, too.

It took far longer than we planned to get to Altamont. Traffic slowed to stop-and-go on the way up the Altamont Pass. After we got off at the exit, traffic got even slower, until it finally stopped and didn’t start again. The concert began without us. Concertgoers started leaving their cars on the side of the gravel road and hiking the remaining mile or so to the speedway. That was the beginning of the discomfort, a discomfort that soon escalated into a kind of low-level misery—and then into violence for many and death for some.

As Rolling Stone magazine later wrote about Altamont, it turned out to be "rock and roll's all-time worst day, December 6th, a day when everything went perfectly wrong.”

By the time we got into the speedway, thousands were sitting on the ground between us and the stage, which was far downhill from us. Huge metal structures for lights and sound equipment rose on either side of the stage; the performers looked to be about as big as bugs. We couldn’t hear much, either.

We put down our blanket and picnic cooler, sat down, and were immediately surrounded by other latecomers who packed in uncomfortably close to us.

At one point, a young man who stood out to me because he was well-dressed with a neatly trimmed mustache walked past us into the crowd carrying a camera. A half-hour later, he stumbled back across a corner of our blanket, holding his hand over his bleeding right eye, and heading for the exit. Someone told us that the Stones had hired the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang as a police force and had paid them with a truck full of beer. Someone also gave the Hell’s Angels huge quantities of red wine laced with LSD. Some of us thought that LSD was the way to peace and enlightenment. Drinkers thought it was the way to make a good fight even more fun. The Angels threw beer cans into the crowd, which in many cases bounced off of heads and caused deep lacerations and skull fractures. And they armed themselves with sawed-off pool cues and wielded them profligately.

The photographer had been beaten by a biker with a pool cue because he took a photo the Hell’s Angels didn't want him to take.

As we learned later, skirmishes between the bikers and concertgoers continued during the rest of the afternoon. Mick Jagger was punched in the head by a concertgoer. A member of the Jefferson Airplane was attacked, too. The tension rose ever higher during the long, hot afternoon, not helped by the fact that the Stones delayed their performance until dark. They wanted to make the lighting of their entrance more dramatic.

When the Stones started playing “Sympathy for the Devil” early in their set, a fight broke out, and they paused. Before they started the song again, Mick Jagger commented into the microphone, “Something very funny happens when we start that number.”

It seems obvious to me that “something very funny” was hell breaking loose.

"Please allow me to introduce myself. I’m a man of wealth and taste. I've been around for a long, long year. Stole many a man's soul and faith."

You can hear the song start, see a disturbance with the Hell’s Angels closing in, and you can hear Mick Jagger’s comments and the rest of the song here.

A few songs later, they started the put-down song, “Under My Thumb,” and a ranting black man tried to get past the Hell’s Angels ringing the stage and was violently shoved back. Hell's Angels gathered around and started beating him. He pulled out a long-barreled gun, some say in a vain attempt to deter them from continuing to beat him. One of the Hell’s Angels stabbed him. When he went down, more Angels circled him, beat him, and kicked him, and he was knifed many more times. You watch the whole dreadful thing, including how the man's hysterical girlfriend with long straight blond hair and a lace vest tries to intervene here:

We didn’t hear about the death until the concert was over. But we did see a man fall from way up on one of the structures beside the stage, and we thought he must have died. On the way out, we detoured past the stage area, and we passed a naked fat man with an erection lying flat on his back on bare dirt, surrounded by sound equipment and cables, but he didn't appear to be dead, just stoned and passed out.

In the New Yorker in 2015, writer Richard Brody wrote that Altamont put an end to "the idea that, left to their own inclinations and stripped of the trappings of the wider social order, the young people of the new generation will somehow spontaneously create a higher, gentler, more loving grassroots order. What died at Altamont is the Rousseauian dream itself."

On January 21, 1970, closer to the actual date of the concert, Rolling Stone magazine published an article titled, “The Rolling Stones Disaster at Altamont: Let It Bleed.” It’s got lots of detailed on-the-scene reporting, but it’s behind a paywall. You might be able to read it, as I did once, before I went back to read it again and was denied access unless I subscribed.

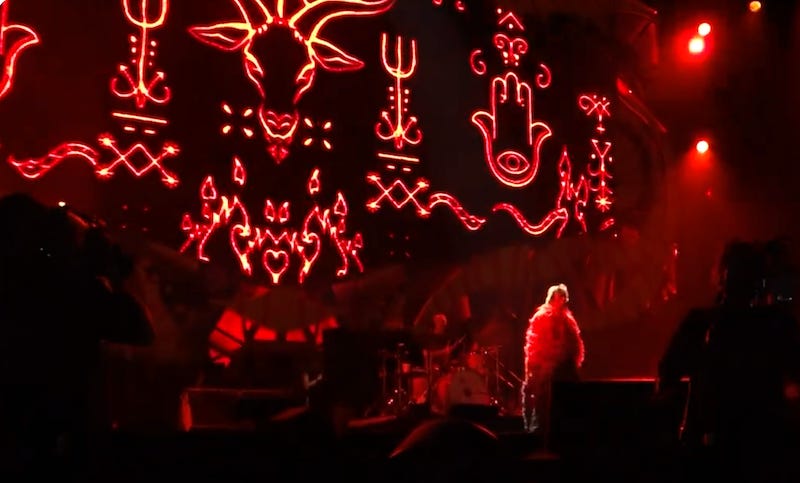

The Rolling Stones stopped playing “Sympathy for the Devil” for many years, and I hoped that what happened at Altamont might have put a bit of the fear of God in them. But they seem to have forgotten. Instead, they began playing the song in concerts again and staging it ever more dramatically.

Here is the song as they performed it in Santiago, Chili in 2016 with blatant satanic symbols, smoke and fire, with Jagger prancing around and wafting a red feathered cloak with a black lining, acting out the role of His Satanic Majesty himself:

A week after the Altamount concert, George and I got married in Golden Gate Park, standing with our friends on the lawn outside of the Conservatory of Flowers.

On July 4, we had our son and named him Liberty. In spite of his earlier resistance to having children, George adored being a father. We moved to the Fargo area in 1970, had a second child, a daughter named Sunshine in 1972—then we got divorced two years later. A while after the divorce, when I stopped thinking George’s name in my head constantly as if he was supposed to be my savior, I started being drawn back to Christianity again.

I returned to the Catholic faith about ten years after I left it, in the mid-1970s. I’ve often said that if God could bring me back, He could bring anyone. That gives me hope and a reason to keep praying for anyone who believes as I once did.

Sometimes I think I’d like to tell Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre, a thing or two. But then, since they’ve both been dead for decades, they already know everything I’d like to tell them.

After the divorce with much loneliness and financial hardship, I finished a B.A. with a double major in Studio Arts and English, and an M.A. with emphasis on writing, studying with Patricia Hampl, who the L.A. Times once called the Queen of the Memoir, who was my Master’s Thesis advisor. I worked on a Ph.D. in American Studies for a year, when I unexpectedly was able to achieve my goal of making a living as a writer—by becoming a technical writer in 1985 as the computer industry took off. I was relieved to find professional paying work that used my skills and could comfortably support myself and my children, and I continued doing some travel writing and other creative writing on the side.

In 1989, a supercomputer company where I worked in St. Paul, Minnesota, had just closed when I was recruited to work at Sun Microsystems in Silicon Valley. I still enjoy picturing in my mind the contrast between how I first arrived in the Bay Area in an orange VW van in 1967 with my old man and how I came back in 1989 by plane with all expenses paid and with all my possessions and those of my two teenagers packed and moved at the company’s expense in an orange Bekins moving van.

My last job as a technical writer ended in 2011, and for the past fourteen years, I have enjoyed being able to contemplate, research, and write about eternal things and publish my journalism, essays, and poems in Dappled Things, National Catholic Register, Sacred Music, Latin Mass Magazine, Catholic Arts Today, ReligionUnplugged.com, Sacred Music Journal, The Catholic Thing, and RoseanneTSullivan.Substack.com. I've also have shown and published some of my art.

For the past three years, I have published many articles about the work many individuals and groups have been doing to build community among Catholic creatives and to foster the return of Catholic work of the highest quality into the mainstream of our culture. Dana Gioia, poet and culture critic, tells people I am the de facto chronicler of the Catholic arts revival, adding I am "the only one on the scene actively and actually seeing what is going on."

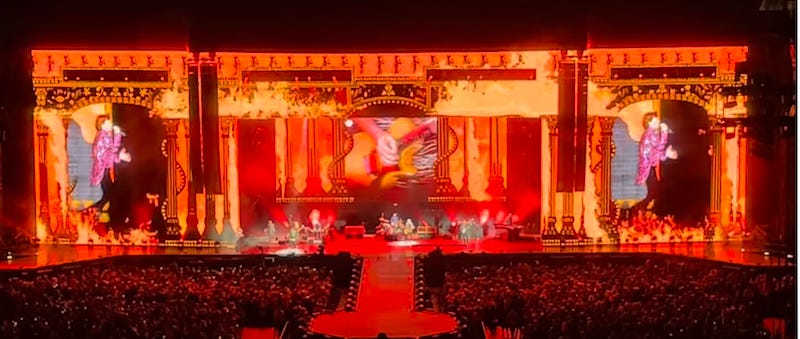

I've changed a lot. But it seems that the Rolling Stones have not. A friend of mine went to their concert in Santa Clara in July of 2024. It was the next-to-last show in the Stones' Hackney Diamonds tour. As a San Francisco Chronicle reviewer wrote after that show, "that the American Association of Retired People is sponsoring the tour is a joke that writes itself."

When I asked, my friend told me, “Yes, they played ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ halfway through the set.” You can watch it here:

Now in his 80s, Mick Jagger is still as wiry and strong-looking as ever. His face is deeply lined, and his arm-waving and strutting around the stage lack much of their former crackling energy. The "Woooo wooos!" in the refrain sound kind of lame.

But even though their homage to old clawfoot is aged and perfunctory and almost a mockery of itself, the Stones, I fear, are still playing with fire.

Some people never learn their lesson.

I hope I did learn mine.

This memoir essay is expanded from when it was first published in the “Reason versus Rationalism” issue of St. Austin Review, July/August 2025, with the kind permission of editor Joseph Pearce.

What a valuable and well-written memoir!