What Makes a Poem Good? According to Dana Gioia and Garrison Keillor

And other musings about an upcoming release of Poetry as Enchantment by Gioia and my encounters with Keillor

When I lived in and around Fargo, North Dakota for four years, starting in 1970, I began listening to an early-morning supposed-to-be classical music show broadcast over KSJN FM coming from St. John's University at Collegeville. The show's announcer was Garrison Keillor. On that morning show, Garrison Keillor interspersed the expected classical music offerings with popular recorded music from artists such as the Beach Boys and the Grateful Dead. He played rock and roll and folk music. He even brought an occasional live act into the studio.

I continued to be a fan of his for many years, with a few years off from disenchantment (more about the disenchantment later). Writers Almanac, Keillor’s short format (five-minute) show ran for twenty years on many public radio stations and for ten years as a podcast. I still get what I call re-runs from the archive in an email that includes a transcript and the option of listening to a recording of each day’s show. For one example of the format, today’s WA from October 7, 2013 has birthday blurbs about writers William Zinnser, Thomas Keneally, and Diane Ackerman, and the poem-a-day is “It Is Marvelous” by Elizabeth Bishop.

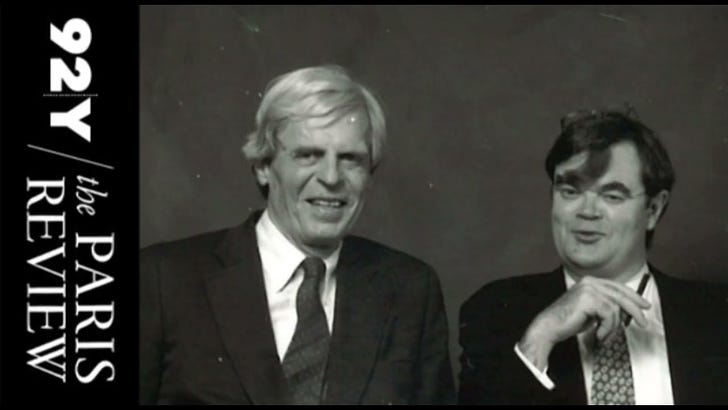

My admiration for Keillor was renewed this past year when I listened to him talk affably, wittily, and intelligently about how he writes, with George Plimpton in an old 1994 interview. The interview was part of the 92nd Street Y Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interview Series.

Also even more recently I came across a favorable review by Dana Gioia of an anthology Keillor edited called Good Poems (2002). Gioia had some quite laudatory things to say about the way Keillor chose the poems for the anthology and about Keillor’s literary gifts.

I first found that review at DanaGioia.com. And then I found it again reprinted in an about-to-be-released book of collected writings by Gioia called Poetry as Enchantment and Other Essays, a copy of which arrived unheralded from the publisher in my mailbox last week, with a printed note the size of a calling card: "Please enjoy this complimentary copy. With best wishes, Dana and Mary Gioia."

Poetry as Enchantment will be released on November 12, 2024, and it is available for preorder at Paul Dry Books. Dana’s book has many other thought-provoking essays and reviews of the quality we all have come to expect from him and I recommend it. But if you can't wait to buy the book, and you’re curious about the review of Garrison Keillor’s Good Poems, you can find it on Gioia’s website here.

Keillor introduces his anthology as “simply a book of poems that got read over the radio on a daily five-minute show called The Writer’s Almanac, poems that somehow stuck with me and with some of the listeners.”

Keillor specifies his editorial criterion: “stickiness, memorability, is one sign of a good poem.” Gioia agrees in his review adding, "The goddess Mnemosyne was the mother of the Muses, and memorability is a governing aesthetic that Horace, Dante, and Milton would have understood, though one does not hear it mentioned much today in graduate schools. . . ."

That's the kind of poetry that I'm looking for too and seldom have found since I read classic poems in grammar school, poems that stick with me, that express something I want to remember in memorable charming language.

Dana continues, "Good Poems left me grateful for Garrison Keillor, whose Writer’s Almanac has probably done more to expand the audience for American poetry over the past ten years than all the learned journals of New England. He understood that while most people don’t care much for poetry, they do love poems, provided they are good poems. . . . Presenting only one poem a day at the end of Writer’s Almanac, Keillor has engaged a mass audience without either pretension or condescension. A small victory perhaps, but one that restores faith in the possibilities of public culture."

To pick one little nit with one thing Dana wrote in the essay, Garrison isn't Lutheran, although he often makes gentle fun of Lutherans in his stories. He was raised in a tiny sect called the Plymouth Brethren, and from what I read in his Substack, he currently attends the Episcopal denomination.

Following are some more recollections of my own about Keillor.

About the time Keillor was starting his radio show on KSJN, my husband, George, and I, both late-bohemian-proto-hippies in our early 20s, had moved with our baby boy Liberty to Fargo to live with his parents for a while. We moved to Fargo, over my strong objections, from the Haight Ashbury hippy district in San Francisco, because George had unilaterally decided to take over his father and mother's greeting card distribution business. I had thought he was going to finish up his college degree and get a more intellectual type of job.

I had grown up around Boston, lived in the Lower East Side of New York for a summer, then most recently lived with George in San Francisco for over three years, and I was ambitious and wanted to live where things were happening, where the scene was, not in some backwater like Fargo. We also had a shared ambition in common with many of our peers in the Haight. We wanted, as the popular saying was, "to get back to the land." But I didn't expect to do it without a community of others of like-mind around us.

Our more affluent Haight Ashbury friends, some of them with trust funds, were buying land and setting up communal farms in rural Oregon or in towns like Santa Rosa in Marin County, California. I never expected that George would bring us to North Dakota and leave all the like-minded with-it people behind to strike out on our own.

I soon learned that Fargo was a matter-of-fact small city of neatly kept mostly single-family homes and that Fargo's main reason for being was as a supplier of goods and services for the farms on the surrounding prairies. The ways of that place and of its inhabitants were strange and new and not at all simpatico with me back then. (They grew on me, but that’s another story.)

George's practical Methodist relatives put no stock in literary and artistic achievement and they were uninterested in creativity and the intellectual life. I’ve seen Keillor complain about that trait of the people he grew up with too, who believed that learning and artistic endeavors were a waste of time.

(My in-laws’ simple virtues eventually grew on me too, but that too is another story.)

I’m telling you all this background to help explain what a relief it was to be able to regularly listen to the wry baritone voice of the literate announcer who was amusing himself and his hearers by doing clever sendups, both corny and ironic, of radio commercials while playing against the expectations of what a more usual stuffy classical music announcer would sound like.

He also did something else I'd never heard of anyone doing before. He invented a town called Lake Woebegon—that doesn’t exist—touting local businesses and products—that don't exist either, such as Ralph's Pretty Good Groceries (whose motto is "If you can't find it at Ralph's, you can get along (pretty good) without it;” Jack's Auto Repair (whose motto was "All tracks lead to Jack's where the bright, flashing lights show you the way to complete satisfaction"); Bebop-A-Reebop Rhubarb Pie (“One little thing can revive a guy, And that is some homemade rhubarb pie; Serve it up, nice and hot; Maybe things aren’t as bad as you thought.”); and Powdermilk Biscuits (“Heavens they're tasty—and so they’re so expeditious").

Around that time, in 1970, Keillor's extremely short short story "Local Family Keeps Son Happy," appeared in The New Yorker. How short? It took up less than two-thirds of a page, with the other third taken up by one of the magazine’s famous cartoons.

“[I]t just came in over the counter and it was terrific. It was about the parents of this 16-year-old boy who were worried that he was rather quiet and unresponsive. So they moved in a local prostitute for him and his problems disappeared. One of her accomplishments was cooking 'fancy eggs' and he ended the piece with the recipe. I'd never seen anything like that before and it was just wonderful. We got in touch with him straight away and he began to send us some great stuff." —New Yorker fiction editor Roger Angell (as quoted in “Minnesota Zen master,” by Nicholas Wroe published 5 March 2004 at The Guardian)

Publication in The New Yorker had been Keillor’s dream for a long time. I later studied with memoirist Patricia Hampl, who told us in a class she used to be a classmate of his at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis when they were both working towards degrees in English. She told us that he always used to walk around campus rather obviously carrying a copy of The New Yorker under his arm.

At twenty-eight years of age, Garrison Keillor achieved the dream of many other writer-wannabees, and he did it his own way—by writing a ludicrously fake news story affecting the tone of a small-town newspaper. He described, as blandly as if he was reporting on a dinner party, a shocking decision by two seemingly practical-minded parents to keep their sixteen-year-old son home by bringing in a twenty-four-year-old prostitute released to them on probation, who not only keeps the son happy, but his fancy woman cooks him her fancy eggs recipe with onions, green peppers, and tomato sauce for breakfast. What I’m trying to tell you is that Garrison Keillor is not just some rube from the prairie. I hope that’s getting across.

That story was prophetic of Garrison Keillor’s lifelong style. When writing for his radio shows, he mostly kept it clean, with a smattering of scatological humor in his yearly Joke shows. I said “mostly.” One year a couple of decades into the show’s run when he seemed to me to be running out of material, he started telling cat stories in his monologues that verged into the bizarre with intimations of interspecies love (ick)—which is when I stopped listening. And when he wrote for other audiences, he wrote about anything he pleased. Raunchy seemed to be what pleased him the most when writing for an audience outside of Prairie Home Companion fans.

Garrison Keillor’s status among Minnesotans was elevated by that New Yorker sale which gave him a stamp of approval from the East Coast's cultural elite. When a year later, in February 1971, he was told by management to rein in his creativity on his radio show, he played "Help Me, Rhonda," in protest, as I remember it, nonstop during his show for a few days, and then he quit. The New Yorker paid about $1,000 for stories in those days, which is the equivalent of $9,183.21 today, so he was able to support himself and his wife and son as a freelancer. But he was back to doing both again when they gave him back his morning show at KSJN in October.

Sometime around 1980, Patricia Hampl and Garrison Keillor both started talking publicly about a taboo subject. Not one of the obvious taboos, you might expect, perhaps. They talked about being ugly. I was surprised. I hadn't thought about either of them as ugly. And besides, it’s not something usually talked about. Even though whether or not people are attractive has a great effect on how they get on in this world.

True, Trish's teeth splayed out but she had an otherwise pleasant face and a trim attractive figure, and she dressed tastefully in a restrained bohemian chic woman professor style. I don't remember specifically what she said about being ugly, except that I do recall once years later that I came across an interview with her in which she mentioned that her husband fell in love with her because he saw her inner beauty. She told us in class once that she was afraid to have her teeth straightened. But I see by more current photos that she did have dental work done, eventually, and her teeth no longer protrude.

The next time I attended one of Garrison's shows after I heard him talk about being ugly, I looked more closely at him, but what I saw still didn't make me apply the label of ugly to his looks. He is big about 6' 4" and slouchy, sort of the opposite of buffed. His straight unruly hair often goes widely awry, and his face is the opposite of craggy. He is not an Adonis. He just is what he is.

I only remember one specific thing Keillor had said at the end of his monologue about being ugly, that it isn't important to be attractive to everybody, but just to one particular somebody.

I found that a lovely humble thought, but then I found it sadly ironic when years later it came out how promiscuous he had been with the women who worked with him on his shows. He commented once that as sales of his first book rose so did women’s interest in him. His looks didn’t seem to stop him from being able to take advantage of his status as a famous writer.

Garrison Keillor is also often quoted as saying he “had a face made for radio.”

That reminds me that I hadn't thought of Dana Gioia as ugly either. But I remember coming across two interviews in which he referred to himself that way. The following quote is from writer Mary Tabor who interviewed Gioia on July 20, 2013 about his poetry collection titled Pity the Beautiful, here: Dana Gioia’s 'Pity the Beautiful': A talk with a major poet.

Tabor: In the "title poem I see the idol named: ‘Pity the beautiful,/ the dolls, and the dishes,/ the babes with big daddies/ granting their wishes.’ Do you raise pity not so much against the idol but perhaps in compassion for the idol?

Gioia: It’s a poem of compassion rather than jealousy or envy. There are people who are so lovely that life takes care of them, but when they lose their beauty, they don’t toughen up the way us ugly people do—

Tabor: Oh, you’re pretty good looking, sir.

Gioia: I’ve got the looks for radio.

I agree with Tabor.

I don't know who came up with that line first about having the looks for radio, Garrison Keillor or Dana Gioia. Or maybe it’s a case of, you know, great humorists think alike?

On July 6, 1974, Keillor started a new weekly live radio variety show on Saturday nights called “The Prairie Home Companion.” The way I understood it, he had gotten a grant from a Minnesota arts organization to start a live radio show featuring talent from Minnesota only, a more tongue-in-cheek version of Grand Old Opry. (The Minnesota-only scope changed over time until many performers like Chet Atkins regularly appeared.)

I got to meet Keillor through a married couple who were working on English degrees at Moorhead State, the two-year college I attended for a while, a few miles away from Fargo, on the Minnesota side of the Red River. Theyknew some of the performers on APHC, including Peter Ostroushko, the genius Ukrainian mandolin player, and I attended an after-party they threw for the performers one night after the APHC crew performed in Fargo on one of its tours. I was divorced and I’d moved into Moorhead from the farmhouse on five acres my husband and I had rented twenty-five miles away, five miles from the small town of Barnesville.

I remember the woman's name is Penny and I can't remember her husband's name, but that's not important to this story anyway.

At the party, Peter Ostroushko and I started what I thought of as just an enjoyable conversation with a man with a unique musical talent, but something about our interchange made Penny come over and pointedly remind him about the girl he was living with at the time. I wasn’t looking to start anything. But I had been hoping to meet Garrison at that party, disappointed he didn’t show up.

The next time I saw Penny, I asked why Garrison hadn’t gone to her party. Garrison had skipped the hours of jamming and getting high with the musicians after the show, and went back to the touring van by himself. I guessed he wasn't comfortable with small talk.

I have another anecdote that seems to confirm that impression. It happened a few years later after I got divorced and moved with my two kids to the Twin Cities.

From time to time, I would bring my kids to the live show in St. Paul. I remember we attended at least one of the shows that were occasionally held outside in good weather early on one lovely summer Saturday evening. Another time, Penny got us backstage passes. We were briefly introduced to Garrison, and we watched the show from the wings at the World Theater. On another occasion, my kids and I watched the show after doing some volunteer work to get free tickets, and then we attended a dinner put on for the volunteers afterward with Garrison Keillor.

At that party, Keillor started hanging around with my second child, my daughter, Sunshine. This is how that happened. Sunshine was 11 years old at the time, and as I've written elsewhere she was so almost preternaturally talented and determined, that she amazed me. I was still an undergraduate studying art and writing, and I was one of the editors of a literary magazine called FallOut, at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, when I took Sunshine with me one afternoon to meet with one of the other editors at his apartment near the Minneapolis Art Institute. It turned out he was casually cohabiting with a woman who had a daughter about Sunshine’s age. When Sunshine found out the girl was a student at Children Theater School, she would not stop until she overcame all obstacles to get herself in. I couldn’t afford to pay her tuition, and I didn’t think it was necessarily a good thing for her to do, but she applied for and got a scholarship, and she kind of bowled over my objections.

When we went to the school to enroll her before classes had started, we saw a poster announcing a casting call for a production of “Annie,” the musical, at a dinner theater. The audition was teeming with other girls who had been taking singing and dancing and acting lessons, but Sunshine threw herself into the audition, as she threw herself into everything. At the end of it, she’d gotten cast as one of the orphans in the show, even though she’d never taken a single class. So even before her first day at the Children’s Theater School, she was already a paid performer in a dinner theater six nights a week.

After we ran into Garrison at the volunteer’s party, and I bragged a little to him about Sunshine’s acting, he spent the rest of the evening pal-ing around with her, kindly flattering her in a little made-up scenario that he was honored to be with her since she was a famous actress. There was not a bit of creepiness about it, I think, it was just a humorous way of his to avoid the awkwardness he seemed to feel at social gatherings and make my little dynamo of an aspiring actress daughter feel special.

The APHC show ended in 2016.

One year later, at the height of the #MeToo movement, a single accusation of unwanted flirting and touching from a woman who worked with Garrison Keillor (according to Keillor an accidentally misplaced comforting hand around the woman’s waist . . . ) derailed his career. Accurate or not, what happened to him after that illustrates the trigger-happy rush to judgment and cancellation of public figures that often happens these days, without a trial, in this case on the word of a single accuser.

Other women came forward and spoke about his affairs with women, but all the accounts seem to agree the affairs were consensual.

Some of the women complained that he flattered the writing of certain women because he was attracted to them, even if sometimes by objective standards their writing of the women he singled out for attention was not that good. One woman said that when he started sending her flirtatious texts about how attractive she was after she had been so elated that he had picked her to write with him, she lost her confidence in her writing, permanently.

Garrison was admittedly a serial womanizer, but one accusation of harassment and other intimations of a power imbalance between employer and employees at a time when there seemed to be no rules about such behavior should not mean instantaneous career death administered by public opinion.

He has since then gradually rebuilt his image as a folksy humorous guy happy in his seventies and eighties (he’s now 82) who adores his current wife, and he started touring and performing live again after some years of banishment.

However, I do always snicker a little when I see one of his current lines is that one secret to his success is that he married well. He has to be referring to his latest wife, who is a much younger beautiful violinist he married after two other wives and a lot of affairs. It is laudable, I suppose, that he is able to stay faithful to this third wife, even though traditionally the first marriage is the only valid marriage (as Jesus Himself said, God hates divorce).

May God give him grace and true contrition for whatever sins he needs to repent before he faces his personal judgment. May God give the same grace and contrition to me, and to us all.

I am still doing a show I started in 1974, which is like winding a ball of twine until it gets to be 50 feet in diameter and your hometown puts up a sign, “Home of Wilmer Sneed, Creator of World’s Largest Ball of Twine,” and there it is, under a glass dome, and people take pictures of it. I started the show for the usual reason: I craved attention, having been a dweeb and dork in school, and in radio I could create a handsomer version of myself. Talent was not a factor in my vocational choice, though of course after you’ve worked at something for decades you do sort of get the hang of it.—Garrison Keillor My goal for 2024, as I see it now

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the launch of the first A Prairie Home Companion show in 1974, Garrison Keillor has been touring around the country There is still one APHC show coming up in Atlanta, on November 8, at 7:30 PM. And there are other solo shows listed as coming up in Dublin, London, Edinburgh, California, and Texas on the poster below.

If you are so inclined, after all this, you can keep up with his regular posts at GarrisonKeillorSubstack.com.