Happy Birthday, Saint Thomas More

Communist hero and great-grandfather of socialism, these are not epithets we usually hear being applied to St. Thomas More. Read on to find out how and why this came about.

I've written about this strange and little-known fact that St. Thomas More was revered by the Bolsheviks as a Communist hero and great-grandfather of socialism a few times in other articles (including “The Surprising Utopian Socialism of Saint Thomas More and Its Long-Reaching Effects,” which is part of series of articles on communism for Latin Mass Magazine). Most of you who read this are probably not LMM readers, so this news won’t be old for you. And even if you are, this was heavily reworked, so it may hold some surprises for you too.

The much beloved-by-many-including-me Saint Thomas More, whose birthday is today, had his name inscribed by Lenin’s orders on a monument to Communist heroes after the Communist Revolution.

Author Aaron Zelman, who co-authored a non-fiction book The State Versus the People in 2001, wrote this quip, "More is the only Christian saint to be honoured with a statue at the Kremlin."

It may be hard to believe, but it’s the truth. Except it wasn't exactly a statue and it wasn’t exactly in the Kremlin, and More wasn’t the only one honored there.

The monument on which More’s name was carved in a list of several others was an obelisk, which had been originally erected as a commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty in Alexander Park, near the Kremlin. The Alexander Garden obelisk was erected on July 14, 1914.

The monument was topped with a gilded bronze double-headed eagle. On one side, below the coat of arms of the Romanov rulers in the form of a griffon with a sword and shield, the names of all the Romanov emperors and empresses were carved. An image of St. George was carved in a central cartouche below the names.

After the Bolsheviks took Russia over during the October Revolution in 1917, Lenin orchestrated the demolition of all monuments devoted to the tsars. The obelisk was not demolished but converted to honor Communism's most influential thinkers "who promoted the liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation."

More was listed with eighteen other heroes of the Communist revolution, number nine from the top of the list in Russian as T (shown as the lowercase Latin M ⟨m⟩) Mop. The eagle was shot down and the griffon removed or hidden. The image of Saint George was replaced with the inscription "R. S. F. S. R." (for Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) and "Proletarians of all countries, unite!.”

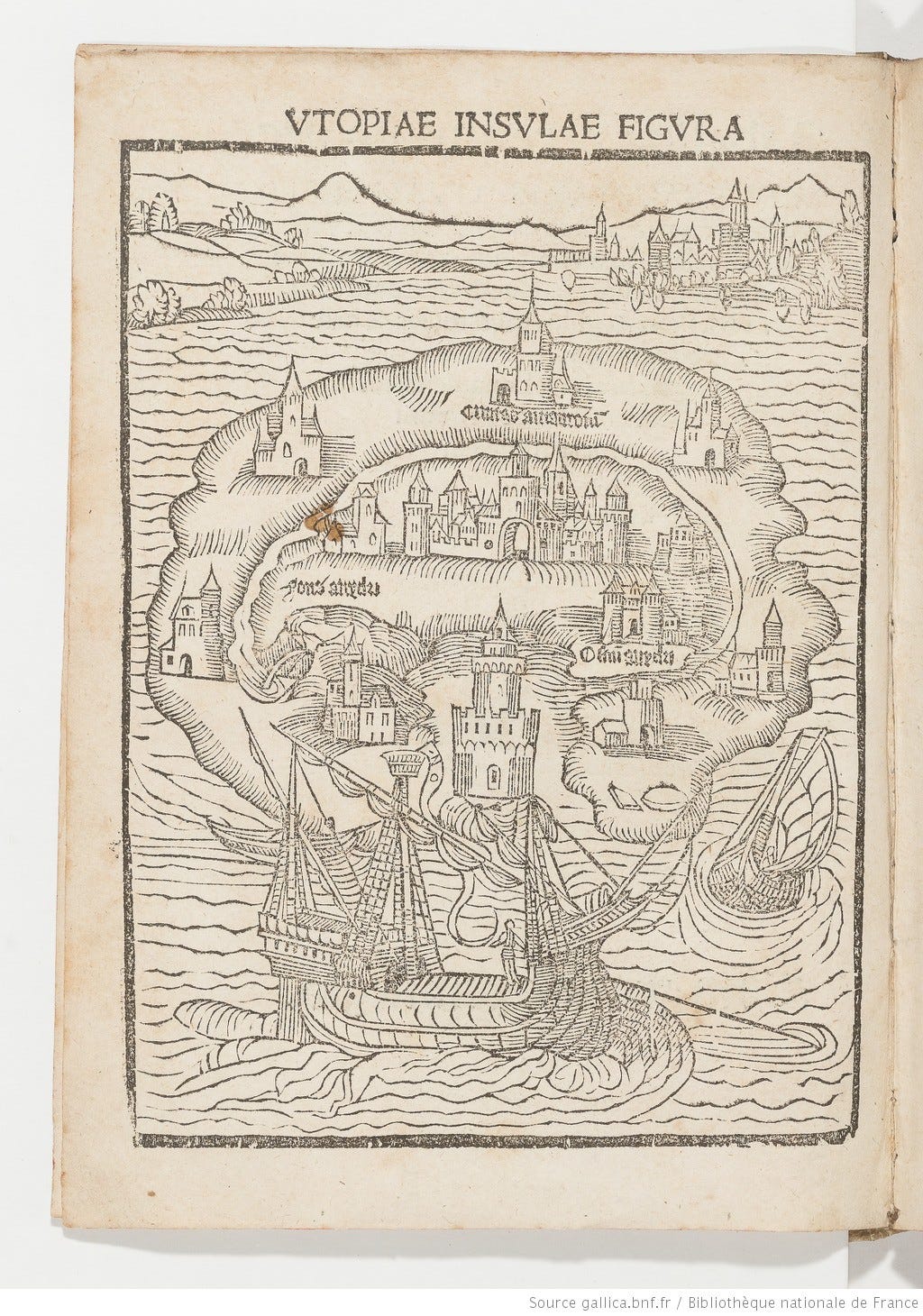

More’s surprising inclusion in the list of heroes of the Russian Revolution came about because in 1516 when Thomas More was a young intellectual of thirty-two he wrote a book that is still influential today. It was titled in Latin in the prolix style of his day: De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia (translated, Of a republic's best state and of the new island Utopia).

And the subtitle is even longer: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia, which translates, "A truly golden little book, no less beneficial than entertaining, of a republic's best state and of the new island Utopia.”

The famous book is commonly known as Utopia, for short.

More’s Utopia was a fictional travel story about the discovery by a European of an island called Utopia, supposedly located in the New World somewhere near Brazil.

More was a friend of the Dutch Renaissance humanist scholar, Erasmus, and, like Erasmus, More was a Renaissance man of letters, long before he later went on to be a statesman in the English court. More was reluctant but consented to serve King Henry VIII in multiple capacities, as Lord Chancellor and as a privy councilor, a private advisor to the king.

Catholics rightly honor More as a saint who was beheaded under Henry VIII’s orders for standing up for marriage. So it will probably be a surprise to many Catholics that More's Utopia was socialistic.

It is also surprising that More's ideal society had also several characteristics that are in direct contradiction to Catholic doctrine and practice, such as euthanasia, easy divorce, married clergy, and the ordination of some widowed women, but they are not as relevant to this discussion as the socialism he described. From the writings from the end of his life, we can see he was a devout, humble, and obedient Catholic. One can surmise he changed any ideas he had that contradicted Church teachings as he got older and more pious.

What is most intriguing is how long the socialist ideals More presented in his Utopia have endured and how enormous their influence has been.

The first society constructed on the ideals of More's utopian socialism was created in the New World within 20 years after Utopia was first published. More's utopian socialism continued to be taken up and embraced as an ideal long after More's death and it has been applied in many other ways, some if not all of which would have certainly appalled him.

The word utopia was coined by More. Many claim that the word Utopia is derived from the Greek οὐ ("not") and τόπος ("place") and that it means no-place. With that translation in mind, they claim the book is a satire, and the author never intended it to serve as a model for any real place. However, the fact is that in English, the "u" in Utopia is actually pronounced "eu," which is derived from the Greek εὖ ("good" or "well").

This claim that utopia meant "no-place" persists to this day, even though More himself wrote in an addendum to his book that he intended Utopia to mean not a u-topia (a no-place) but a eu-topia, a good place, "a place of felicitie."

A Real-life Catholic Utopia in the New World

Hardly anyone outside of Mexico knows about this, but the first implementation of More's Utopian socialism was made by a Spanish-born Catholic bishop Vasco de Quiroga in the New World, and it was remarkably successful. During the 1530s, within a few decades after More published his Utopia in 1516 and five years before More was beheaded, benevolent Bishop Quiroga of Michoacan, Mexico—a region larger than France—used his own money to fund utopian communities to protect and instruct the indigenous people of the region, who had been brutally exploited by Spaniards who had preceded him.

The Catholic Utopian communities Quiroga created included up to 30,000 converted Indians. Quiroga died in his 90s in 1565 and the communities he founded flourished long after his death. The communities remained in existence for an impressive 340 years, until they were legally disbanded only in 1872.

Quiroga's Catholic utopias were directly based on More's Utopian ideals (Quiroga carried a copy of the book with him on his travel), and they were implemented as communities of equals who all worked only six hours a day, with a two-hour lunch break. There was enough for everyone, but no luxury, and everything was shared in common. They were called "Pueblos-Hospitales de la Santa Fe” (Hospital-Towns of the Holy Faith).

Sixty-eight years after Quiroga's death, an eye-witness account by an Augustinian Friar Juan de Grijalva described the pueblos-hospitales as places where converted Indians came from different regions with their entire families because they wanted to live in the manner of the apostles in a religious way of life. The poor and the sick were cared for. Everyone who voluntarily joined those communities not only worked equally but engaged in prayer and contemplation together. The way of life he described was a type of monastic communalism lived out by devout laypeople.

Quiroga is greatly honored in Mexico to this day. The descendants of Mexicans who lived in Quiroga's communities are said to light candles before his image. And many are still renowned for the crafts in which their forebears were instructed in Quiroga's pueblos-hospitales. In his 1990 visit to Mexico, Pope John Paul II hailed Quiroga for "heroic missionary and civilizing work." The "Roman phase" of the cause for the canonization of Vasco de Quiroga was opened on April 29, 2014.

Christian Communalism in the Early Church and Monastic Life

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn mentioned that More had been presciently aware that communism needed enslavement and forced labor to survive. Solzhenitsyn wrote that this had been "...foreseen as far back as Thomas More, the great-grandfather of socialism, in his Utopia," which included slavery.

The communism the young Thomas More portrayed in his Utopia was his reaction as a young man to the vast disparities between the rich and the poor under monarchy, and he applied the principle described in the Acts of the Apostles where the early Church shared everything in common to his fictional society.

Where More wrote that everyone in Utopia did six hours a day of agricultural work, lived simply, and shared everything in common, he was probably imagining how a society could correct the inequalities of his own day, the appalling excesses of the idle rich in contrast to the poverty of the poor. I have often wondered myself how it came about that Catholic life moved away from the Christian way described in the Acts of the Apostles, where all believers had all things in common and continued with one mind.

Here is what St. Luke wrote about how the early Christians lived.

"And all those who had believed were together and had all things in common; and they began selling their property and possessions and were sharing them with all, as anyone might have need. Day by day continuing with one mind in the temple, and breaking bread from house to house, they were taking their meals together with gladness and sincerity of heart . . .." Acts 2:44-45.

One problem that I now see with that ideal is that communal ownership of everything is not conceivably possible in a godless society. I do believe it would be possible in a society of saints. It is practiced in a limited way in some monasteries, but in such places, voluntary poverty is vowed along with obedience to authority, all who come to live there are screened to exclude criminals and the rebellious, and exploitative behavior would not be tolerated.

Archbishop Fulton Sheen gave us one hint about why utopias based on manmade ideals turn into dystopias in this quote from his book, For God and Country:

“Because the world assumes that evil is wholly external or social, it falsely believes that its remedy lies in the domain of politics and economics since they deal with the externals or with what a man has rather than what he is.”

In Utopia, atheists were viewed as dangerous because there was nothing to stop them from doing exactly what they pleased. Communism is an atheistic utopianism, hence of course the epithet “godless Communism.”

Another famous quote from Solzhenitsyn points to the single root cause of the dystopian lives of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union after the Communists took over:

"Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.' Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.'"

From an email: Hi Roseanne,

Thank you very much for this well-written summary of the influence of Thomas More in communist circles. I had not consciously realized this. Your writing connected many dots for me and set off many further ponderings in my head, among them regarding heaven, the Acts of the Apostles, the early Church, the imitation of God by Satan, and God's use of error and saints to identify and purify His followers. One of my most favorite movies is a Man for All Seasons, which you no doubt know is about St. Thomas More.

Thanks again,

Jessica