Honoring the Great White Martyr Ignatius Kung, Persecuted Bishop of Shanghai

White martyrs are those holy men and women who suffered intense persecution for their faith without shedding their blood.

On Saturday March 15, 2025, Cardinal Raymond Burke preached at a Pontifical Requiem Mass celebrated by Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone at Star of the Sea Church in San Francisco. The Mass was in honor of the 25th anniversary of the death of heroic white martyr Ignatius Cardinal Kung.

At 10:30 AM, before the Mass, Dr. Jennifer Donelson-Nowicka led a schola in singing the hymn “For the Martyrs of Chinese Communism.” The hymn was commissioned by the Benedict XVI Institute from composer-in-residence Frank La Rocca, with the text by poet-in-residence James Matthew Wilson.

To learn more about the history of Ignatius Cardinal Kung, you might want to read two articles of mine that I’ve merged and edited below.

Bishop Kung Was Tricky That Way, and Other Stories of the Saintly, Stubborn, Persecuted Ignatius Ping-Mei Kung of Shanghai

During the night of September 8, 1955, Ignatius Ping-Mei Kung, Shanghai’s first native Chinese bishop, was arrested by Communist authorities. Before the night was over, police arrested more than three hundred Catholic priests, religious, and lay people in seminaries, churches and private homes around the city. Twelve hundred Shanghai Catholics were arrested by the end of that same month.

Bishop Kung was a Shanghai native, and his family had been Catholic for at least five generations. Few westerners are aware of this, but the Roman Catholic Church has had deep roots in China since the sixteenth century, and a large concentration of Catholics still live in Shanghai, which is one of many concentrations of Catholics in the nation. The government claimed religious freedom was a basic right, so the Catholics were arrested because they were said to be counterrevolutionaries. They knew the real reason was because they would not renounce their loyalty to the Pope and join the Communist-created church.

A few months after his arrest, Bishop Kung was brought out to a show trial that was held in a former greyhound racing stadium where mass trials and executions were held almost daily.

Everyone in Shanghai had heard about or seen the mass arrests, sometimes of thousands at a time, with the arrested ones being driven off in red paddy wagons, and everyone would have known about the ongoing executions at the stadium where thousands of Shanghai residents were brought to witness the proceedings. Bishop Kung probably knew he was was facing death if he did not cooperate. Wearing only Chinese pajamas with his hands tied behind his back, the diminutive, 5 feet tall but audacious Bishop Kung was thrust before a microphone to confess his “errors.”

Instead he shouted: “Long live Christ the King! Long live the Pope!”

Many in the crowd responded, “Long live Christ the King! Long live Bishop Kung!”

The guards pointed their guns at the crowd, and the cheering stopped. The authorities quickly whisked Bishop Kung away to solitary confinement and to continued and prolonged attempts to wear him down. He had a whole floor to himself at the prison, he later told reporters, and everyone was forbidden to make eye contact with him, except when they were trying to indoctrinate him in long grueling sessions. He continued to give this same answer whenever he was asked to renounce the Pope, “I am a Roman Catholic Bishop. If I denounce the Holy Father, not only would I not be a Bishop, I would not even be a Catholic. You can cut off my head, but you can never take away my duties.”

Bishop Kung was out of sight, but the world had not forgotten his heroic sacrifice. Two years after Kung’s arrest in 1955, Bishop Fulton Sheen wrote in his Mission magazine in 1957: “The West has its Mindszenty, but the East has its Kung.” (Jozsef Mindszenty, as you may know, was the leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary, who was given a life sentence by the communists in 1949 because of his resistance to the their policies.)

Five years after Bishop Kung’s arrest, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to life in prison. Kung was imprisoned for a total of thirty years, unable to correspond with anyone, even members of his own family. He was forbidden to say Mass, and he was not permitted to read the Bible. Many other loyal Shanghai Catholic priests and laity endured the same kinds of long prison sentences and either died in anonymity or were released after decades as old, broken, men and women.

When Bishop Kung Tricked Them Again

I enjoy imagining the frustration of the Communist officials twenty-nine years after the scene in the stadium, when Bishop Kung tricked them once again.

This event occurred in 1984 during an eleven day trip to China by Cardinal Jaimie Sin from the Philippines, whose father had been Chinese. Cardinal Sin asked the authorities to let him see Bishop Kung during his visit to his ancestral homeland. Probably because of international protests about the imprisonment of Bishop Kung, who was on an Amnesty International list of prisoners of conscience, they concurred.

The Communists set up a show meeting on October 27, 1984. They seated Cardinal Sin and Bishop Kung at opposite ends of a long dining table and surrounded them with Communist leaders and bishops of the CCPA. Cardinal Sin and Bishop Kung were not allowed to talk personally to each other, but they slyly used their wits to get around all the machinations that had been put into place to keep them from communicating.

Cardinal Sin was well known as a great joker—he would tell people he lived in the House of Sin, for example—so his part in what happened that night was consistently in character for him. Cardinal Sin invited each attendee to sing a song during the dinner, which is a common practice in the Philippines.

When Bishop Kung’s turn came, he looked directly at Cardinal Sin and began to sing in Latin the Gregorian chant that uses the words by which Christ made St. Peter the first Pope. “Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo Ecclesiam meam (You are Peter and upon this rock I will build my Church).”

After Bishop Kung sang just a few bars, a Bishop of the CCPA told his superiors of Kung’s ruse. They ordered Bishop Kung to be silent, but he looked at Cardinal Sin again and finished the song: “Et portæ inferi non prævalebunt (and the gates of hell will not prevail against it).” These word are sung multiple times every year during Latin Masses and the Divine Office for several feasts of the traditional liturgical calendar. Below are the words sung during the Alleluia on July 29, the feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

In the Heart of the Pope

Bishop Kung did not know then that he had been secretly elevated to the College of Cardinals six years earlier. He found out only after his release–first from prison later in 1985, and after he was released from house arrest in 1988, when he moved with his nephew to Stanford, CT, to get medical care. Cardinal Kung said this in an interview in 1999, “One year after my arrival in the United States, I was well enough to go to Rome where I was warmly received by Pope [Saint] John Paul II. During that meeting, I was told by the Holy Father that I had been elevated in 1979, in pectore, to the College of Cardinals. I kept this a secret until our Holy Father announced it to the world on May 29, 1991.”

In pectore means in the heart of the Pope. Elevations in pectore are sometimes done when a pope wants to honor a cleric while not putting him or other Catholics in danger in a situation where the Church is being persecuted.

Cardinal Kung finally received his red biretta on June 30, 1991 from the pope.

“When the Pope presented Cardinal Kung with his red hat in June 1991, the 90-year-old raised himself up from his wheelchair, put aside his cane and walked up the steps to kneel at the feet of the Holy Father. Visibly touched, the Pope lifted him up, gave him his cardinal’s hat and stood patiently as Cardinal Kung returned to his wheelchair to the sounds of a seven-minute standing ovation from 9,000 guests in the Vatican audience hall.”–”A Hero Dies in Exile” by Brian McGuire, National Catholic Register, Sunday, Mar 19, 2000.

Christ's words of institution of the papacy are in gigantic letters 2 meters high on a gold background at the base of Michelangelo's dome in St. Peter's Basilica, illuminated by the light of sixteen windows

A polyphonic version of “Tu Es Petrus,” by Palestrina, being sung at the last public Mass of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI on Ash Wednesday, February 13, 2013

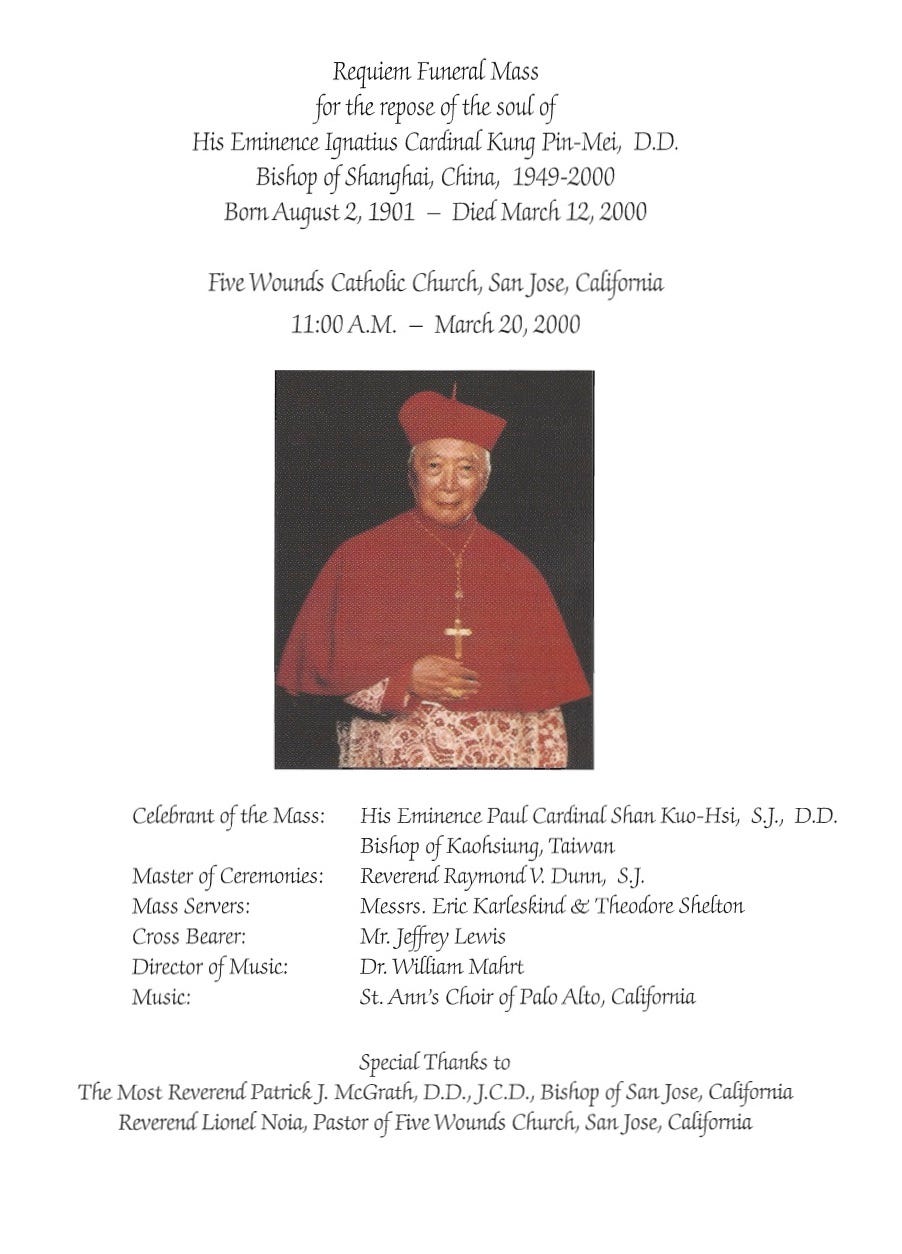

The Miracle and the Hope: Cardinal Kung's Requiem and Burial

Many think it was providential that Ignatius Cardinal Kung of Shanghai got his wish to have a traditional Requiem Mass in spite of how it was nearly impossible to get permission for the pre-Vatican II form of the Mass at the time of his death in 2000. This part of the story describes why the Mass was arranged in San José and how the permission was obtained—after a few setbacks. This part of the story also tells about the hope that motivated Cardinal Kung's nephew to bury his uncle in Santa Clara, California, far from his uncle's place of death on the East Coast of the U.S. and even farther from the Shanghai Cathedral where exiled Cardinal Kung had longed to be buried under the altar as its bishop.

Cardinal Kung's Death in CT

When Ignatius Cardinal Kung died in March of 2000 at the age of 98, he was in exile far away from his Shanghai homeland, living in his nephew's family home in Stamford, CT. As Fr. George W. Rutler wrote in a Crisis magazine article, when Kung first went to Hong Kong from Shanghai for medical care after his release, he had been unsettled by how much had changed in the Church while he had been in prison. Just for one small example, Kung "was amazed that Catholics no longer observed the Friday abstinence that he had kept for 30 meatless years."

In order to realize how difficult it was going to be for Cardinal Kung's friends and relatives to be able to arrange for a traditional Requiem Mass after he died, you have to realize that after the revised Mass of 1969, once called the Ordinary Form by Pope Benedict XVI, and now called the novus ordo or new Mass, was introduced, the new form of the Mass became almost the only Mass allowed to be celebrated in the Roman rite of the Catholic Church all over the world. The older form of the Mass, once called the Extraordinary Form by Pope Benedict XVI and now sometimes referred to as the uses antiquor (the more ancient use) and more-commonly as the traditional Latin Mass, was almost completely banned in practice along with Latin, and along with Gregorian chant, between 1969 and 1982, and the traditional Latin Mass was still greatly restricted in the year of Kung's death.

Cardinal Kung's Requiem Mass in CA

Cardinal Kung's Requiem Mass was remarkable because it was unusual in many ways.

The year 2000 was thirty-one years after the virtual ban of Latin and the Extraordinary Form of the Mass, along with Gregorian Chant, after the Second Vatican council. When Cardinal Kung died, sixteen years after the 1984 indult that allowed bishops to give permission in some cases for the traditional Latin Mass to be celebrated, and twelve years after the 1988 motu proprio in which Pope Saint John Paul II urged a "wide and generous" application of the 1984 indult, permission was still hard to come by.

Ignatius Kung died seven years before Pope Benedict XVI’s 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum further relaxed restrictions against the traditional Latin Mass and opened the way for more frequent celebrations.

Arrangements were made for the Requiem Mass to be celebrated at the Five Wounds Portuguese National Church in San José. Five Wounds is a distinctive church modeled on a Portuguese basilica, which preserved its traditional exterior and interior after the Second Vatican Council. To this day, the building still has a high altar at the top of many steps with an altar rail at the bottom, the pews face the altar, and scores of statues of saints abound. Two large mahogany confessionals are on the right wall, and a high mahogany pulpit still stands on the left of the altar. The only architectural modification to suit the new Mass that is apparent in Five Wounds Church is the insertion of a freestanding altar in front of the high altar, to allow what is now the usual celebration of the new Mass with the diocesan parish priest facing towards the congregation.

For a while, things seemed to be going smoothly. Cardinal Kung would not only get his wish for Requiem Mass, but Cardinal Shan of Taiwan agreed to celebrate a Pontifical Requiem Mass in his honor.

Then Bishop Patrick McGrath of San Jose gave permission for Kung’s Requiem Mass, but with one restriction, that the Mass would be celebrated facing the congregation.

In the celebration of traditional Latin Masses, the priest faces the altar, which is understood to be the "liturgical East," so that posture is called ad orientem. The symbolism behind ad orientem celebrations of the Mass can be glimpsed in the definition of the Latin word orientem, which means: daybreak, dawn, sunrise, east. The sun rises in the East, Christ is called the Sun of Justice, the dawn from on high, and His Second Coming is expected from the east.

Some people have been taught to believe a priest facing ad orientem is offensive because the priest is "turning his back to the people." But the result of the priest praying the Mass ad orientem is to take the focus away from the priest and to focus our attention on God. In that way, the priest together with the people face together in the direction from which we look for the Second Coming of the Lord. Even though the orientation towards the people, versus populum, became common after Vatican II, the council did not mandate it.

When the Bishop of San José at first made his stipulation, consternation ensued. It must have been hard to imagine how the people-facing orientation could have been carried off in a traditional Pontifical Latin Mass. Then at some point, to the relief of all those who were trying to organize the Mass, the bishop changed his mind, and he agreed to allow Cardinal Kung’s Requiem Mass to be celebrated ad orientem.

Some say that the bishop removed his restriction because Cardinal Shan of Taiwan was going to be the celebrant, and it would be impolitic to contradict the wishes of a living Cardinal, even if he was willing to contradict the wishes of a dead one.

Cardinal Kung’s nephew, Joseph Kung, has written at the Cardinal Kung Foundation website that the bishop’s change of heart was due to intercessory prayers of the his dead uncle, and he also wrote that the bishop's allowing them to celebrate the traditional Requiem facing the liturgical East was Kung’s first miracle.

On March 20, 2000, an astounding one thousand people attended Cardinal Kung’s Pontifical High Requiem Mass. The St. Ann Choir of Palo Alto sang the Gregorian chant for the Mass along with Renaissance polyphony under the direction of Stanford Musicology Professor William P. Mahrt.

The St. Ann Choir is also remarkable for its endurance, because it had providentially been able to keep on singing Gregorian chant and polyphony at Masses in nearby Palo Alto for more than thirty years by then before, during, and after the Second Vatican Council, long after that type of Sacred Music was virtually banned. (For more about the St. Ann Choir's remarkable achievement, see Miracle in Palo Alto: How the St. Ann Choir Kept Chant and Polyphony Alive for 50 Years.)

The choir sang the hymn “Tu Es Petrus” (You are Peter), a poignant reminder of Kung’s long martyrdom and of the canny way Kung was able to convey his courageous refusal to deny the pope to Cardinal Sin in the face of Communists trying to keep them apart, during the show visit mentioned earlier.

Kevin Rossiter, who had only recently joined the St. Ann Choir at the time of Kung’s funeral, sent me these recollections.

“There were a lot of photographers and people apparently from the (non-communist) Chinese press. The homily alternated between Chinese and English and was very good, telling the usual stories about him (the show-trial, about the singing “Tu Es Petrus” ) but also explaining his political strategy from very early on (e.g., in preparing lay catechists for the time when he knew the church would have to go underground). The cardinal used the occasion to announce the beginning of the case for his canonization. The cards for the funeral with his picture were very beautiful—I have one somewhere, but it has been misplaced during moves, so it's still probably in a box or pressed into a book. Those are the things I remember most. The atmosphere was very joyful.”

St. Ann Choir Director Professor Mahrt also shared with some recollections of Kung’s Requiem Mass:

“At some point the casket was opened for the congregation to pay their respects, and all filed by the casket. At the time I thought, ‘I will probably never again witness the funeral of a saint or see him resting in a coffin.’”

Burial in Santa Clara Mission Cemetery

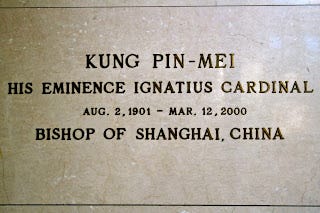

After the Requiem Mass, Cardinal Kung’s body was interred in an above-ground vault in the Saint Clare Chapel at Santa Clara Mission Cemetery.

Before I knew anything about Cardinal Kung, somebody pointed out his marker to me at the doorway to the chapel, and I wondered how it came about that a Shanghai cardinal came to be interred there. Now I understand.

Six years previously, the body of Archbishop Dominic Tang of Canton, another Chinese member of the Church's hierarchy and friend of Cardinal Kung, had been placed in a nearby vault. In a chapter about Archbishop Tang in his book Cloud of Witnesses, Fr. George Rutler recounted that when Dominic Tang was a young priest in Shanghai, Tang “cycled with his friend Rev. Ignatius Kung Pin-Mei from parish to parish to hear confessions.” Tang had been appointed as apostolic administrator of Canton in 1950, the year after the Communists took over. Like then-Bishop Kung, who accepted his ordination as bishop of Shanghai that same year, Tang realized and accepted the persecution he would be forced to undergo as the result of his ordination. Three years after Bishop Kung was arrested, Tang was also arrested, and he spent twenty-two years in prison without trial.

After they both were released and forced into exile, they maintained their friendship. So close were they that Archbishop Tang had died while visiting Cardinal Kung in Stamford in honor of the cardinal's 65th anniversary as a priest and his 45th anniversary as a bishop, on June 27, 1995. After Tang's death, Cardinal Kung’s nephew Joseph Kung had brought Archbishop Tang's body to Santa Clara for interment. It was fitting that after Kung's funeral, the two friends were reunited.

Father Rutler wrote, “His Eminence was buried next to his friend, and both bodies face the horizon in the expectation that the two old men who, in youth had bicycled together will in a great dawn be buried in their cathedrals in Canton and Shanghai."

Joseph Kung wrote these additional details about the burial in Highlights of the Funeral at the Cardinal Kung Foundation website :

"That the bodies of these two Chinese bishops, ever faithful to the Successor of Peter and devoted to their flocks in Canton and Shanghai despite all adversity, are interred above ground expresses the hope that one day their mortal remains will be transported to China and interred, each at the foot of the altar of his respective cathedral. The same hope was expressed when Cardinal Mindszenty was interred above ground in Austria; and the hope was rewarded when his remains were transported back to Hungary.”

Prayer Request

Please pray for this intention, for the Catholics suffering religious persecution in China, and for the canonization of Ignatius Cardinal Kung Pin-Mei.

For more about Cardinal Kung, check out the trove of information at the Cardinal Kung Foundation website, which is maintained by members of his family,

SS: I read it. Really great.

Remark from a friend of a friend of a friend:

Just caught up...yes, my phone was blowing up, but I ignored it as I was reading Roseanne's latest article about Cardinal Kung! So good, I learned so much!

JP sez:

She is a fabulous writer!