Portraying Infinite Love in 2 Dimensions

How can artists best show God's love in images of Christ's Sacred Heart?

Dappled Things Quarterly of Ideas, Art, and Faith is sponsoring a Sacred Heart Art Competition with cash prizes (with no entry fee). Submissions close Sunday, March 31, 2024 at 9 PM CT. See this link for details and how to apply.

This article is an exploration of what makes an appropriate image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, as suggested by Bernardo Aparicio Garcia, founding editor of Dappled Things. (For several years, I posted at the Dappled Things “Deep Down Things” blog, compiled their “Friday Links,” published interviews and reviews in their print magazine, and then at the last Catholic Imagination Conference (my first) I was delighted to finally meet and socialize with Bernardo and his family, along with other Dappled Things contributors, editors, and friends after-hours.)

When I emailed to ask Bernardo’s opinion about some things I’d discovered when searching for guidance about what kinds of images of the Sacred Heart are approved by the Church and what the contest judges would be looking for, he wrote back:

Would you be interested in doing some more research about this and writing up a post about it? The idea would be something that explores the history and tradition of Sacred Heart iconography in a way that illuminates and provides guidance, but without coming down too hard or boxing in artists so much that it discourages submissions. . . . I think the other thing that would be good would be to make clear that the post is not an official guidance from DT about the contest, but rather that the contest gave you occasion to look into this and you're sharing what you found. Do you think that might interest you?

Yes, it interests me, and I hope it will interest you, whether or not you are an artist interested in submitting to the Sacred Heart Art competition.

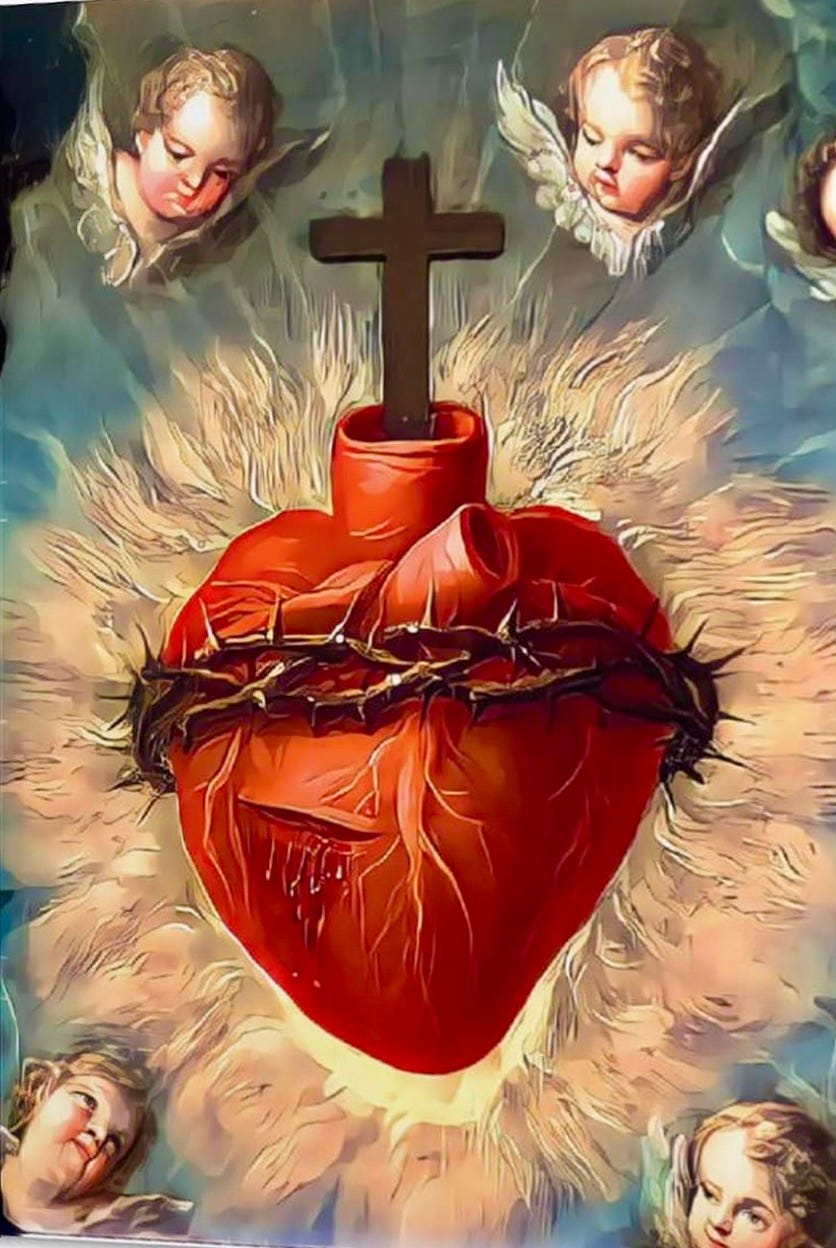

The Sacred Heart as an Emblem, not as an Organ

One of the things I found is a mention by the author of "Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus” in the Catholic Encyclopedia that the Sacred Heart should always be rendered as a symbolic not a physical heart. In other words, the image probably should not look like this.

“It is eminently proper that the heart as an emblem be distinguished from the anatomical heart . . .. A visible heart is necessary for an image of the Sacred Heart, but this visible heart must be a symbolic heart.”—Catholic Encyclopedia, “Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus”

Another thing I looked into is that Susan Altstatt, an accomplished Western artist, once told me she had been admonished that the Sacred Heart of Jesus is never supposed to be portrayed separately from His human form. I haven’t found anything that documents that prohibition.

Through the admittedly unscientific method of googling, I found only one reference to any preference of the Church against portraying Christ’s heart separate from His body, in this article, “Devotion to Sacred Heart increases in Mexico during pandemic.”

Before I get into what the article says, here is a definition of one of the article’s keywords. The word detente in this context means stop, and it is the name given to a small two-sided piece of cloth or a card with an image of the Sacred Heart on one side, a warning against one’s enemy, “Stop, the Sacred Heart is with me,” and often there is a prayer on the reverse. In the earliest versions, the enemy from which the carrier of the detente sought protection was disease in the form of epidemics. When soldiers wore them in the 19th and 20th centuries, the enemy was a bullet.

In recent years, according to the article published June 20, 2020, during the height of the COVID epidemic, disease again became the enemy against which detentes were carried for protection. The article reports on a resurgence in the demand for them in Mexico, where even the president, some say in cynical manipulation of the religious sentiments among his constituents and others say in barely disguised mockery, pulled out a pair of detentes from his pocket during a news conference. He called these and other tokens people had given him, “My bodyguards.”

The following (from the article about detentes) is the only quote remotely against disembodied hearts I’ve been able to find; it claims that devotion to the Sacred Heart must be to Christ resurrected and glorified.

“You don’t see it in the churches, it’s part of the popular piety: You see the heart, you don’t necessarily see Jesus,” said Father Robert Coogan, an American priest in the northern city of Saltillo.

“The church asks that a true devotion to the Sacred Heart be an image of Jesus resurrected and glorified, showing the burning love of his heart and that it not be the heart as a talisman, which is quite popular in Mexico.”

The quote from this one priest in one article cannot be viewed as definitive, since there don’t seem to be any church documents to back it up. Fr. Coogan apparently shares the views of the pastors who after Vatican II replaced the Crucifix hanging over the altar in their parish churches with sculptures of Christ resurrected—which many of us call Ressurexifixes. (Regrettably this was done quite often, even though the General Instruction of the Roman Missal says : “There is to be a cross, with the figure of Christ crucified upon it, either on the altar or near it, where it is clearly visible to the assembled congregation.")

Back to our main topic: if you have heard of any Church regulation requiring the Sacred Heart to be portrayed only in an image of a resurrected and glorified Christ, pray tell me in the comments.

Against Fr. Coogan’s claim, I would offer this. Images of the Sacred Heart separate from Christ’s body were carried or worn devotedly for centuries, by faithful Catholics, saints, popes, religious, and laity, who lived through times of epidemic, of persecution—such as during the French Revolution—and of war, such as its continued use by Spanish soldiers. Blessed Pope Pius IX assigned an indulgence to those who wore one of the emblems, which originally were made by St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, the “saint of the sacred heart,” for her religious sisters, and he composed the prayer that is often printed on detentes.

Open Thy Sacred Heart O Jesus. Show me Its beauty. Unite me with It forever. May the throbbing in all the movements of my heart, even during sleep, be a testimony of my love and tell Thee unceasingly: Lord, I adore Thee. Accept my poor little actions. Grant me the grace of repairing evil done, so that I may praise Thee in time and bless Thee for all eternity.—Prayer composed by Blessed Pius IX.

Neither the blessed pope nor St. Margaret Mary Alacoque had a problem with the Sacred Heart not being portrayed as part of Christ’s resurrected, glorified body.

Then there are Milagros (also known as ex-votos or dijes or promesas), which are religious folk art pieces, and when they are in the shape of hearts they also stand for the Sacred Heart.

Any disapproval of the use of detentes or Milagros seems to me to be more directed against treating Sacred Heart emblems superstitiously, like lucky charms, without due devotion to the immense love of God that led to Christ’s Passion, which Sacred Heart images are intended to convey.

Haurietis aquas

"You shall draw waters with joy out of the Savior's fountain." Isaiah 12:3.

“Haurietis Aquas” (Latin for "You will draw waters") is an encyclical of Venerable Pope Pius XII. Pius XII published this encyclical on May 15, 1956, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by Blessed Pope Pius IX. Then in 2006, Pope Benedict XVI wrote a letter commemorating the 50th Anniversary of “Haeritas aquas” titled, “We Adore Jesus’ Pierced Heart.”

Neither “Haurietis aquas” nor Pope Benedict XVI’s letter offer more-specific guidance for how the Sacred Heart should be depicted, they do offer a lot to ponder about how mystically significant and how important this devotion is to the Roman Catholic Church.

The Heart as a Symbol of God’s Divine Love

What we adore in contemplating Christ’s Sacred Heart is God’s humanly unimaginable infinite love for us, both the uncreated love of the Divine Word and the love of His human heart, since both loves motivated Christ's sacrifice on the cross for us and for His Spouse the Church.

All following numbered quotations are from “Haeritas aquas.”

“75. The Sacred Heart of Jesus shares in a most intimate way in the life of the Incarnate Word, and has been thus assumed as a kind of instrument of the Divinity. It is therefore beyond all doubt that, in the carrying out of works of grace and divine omnipotence, His Heart. . . is also a legitimate symbol of that unbounded love.

The Wound through which the Church Was Born

The wound in the heart of Jesus is significant in this devotion, because when Longinus, the Roman soldier, pierced Christ’s side, his sword penetrated Christ’s heart, blood and water poured out, and the Church was born.

“76. From the pierced Heart, the Church, the Bride of Christ, is born. . . . And He pours forth grace from His Heart."(80)

The water is understood as being for cleansing and is associated with the Sacrament of Baptism. The blood is Christ’s Precious Blood that redeems us, associated with the Eucharist.

“77. From the side of Christ, there flowed water for cleansing, blood for redeeming. Hence blood is associated with the sacrament of the Eucharist, water with the sacrament of Baptism, which has its cleansing power by virtue of the blood of Christ."

The wound in Christ’s heart, therefore is a profound image of God’s tender love.

“78. . . . Hence the wound of the most Sacred Heart of Jesus, now that He has completed His mortal life, remains through the course of the ages a striking image of that spontaneous charity by which God gave His only begotten Son for the redemption of men . . .."

Heart Burning with Love

Flames are usually used to portray how Christ’s Sacred Heart is burning with love for us. Often a cross is shown in the midst of the flames.

“79. After our Lord had ascended into heaven with His body adorned with the splendors of eternal glory and took His place by the right hand of the Father, He did not cease to remain with His Spouse, the Church, by means of the burning love with which His Heart beats.”

Devotion to the Two Hearts of Jesus and Mary

Another important point made in the encyclical is that the devotion to the most Sacred Heart of Jesus should be closely joined to devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the Mother of God.

“124. . . .Let the faithful see to it that to this devotion the Immaculate Heart of the Mother of God is closely joined. For, by God's Will, in carrying out the work of human Redemption the Blessed Virgin Mary was inseparably linked with Christ in such a manner that our salvation sprang from the love and the sufferings of Jesus Christ to which the love and sorrows of His Mother were intimately united.”

Sister Lucia, one of the Fatima visionaries, insightfully pointed out the extraordinarily intimate union of the two hearts and the hearts’ blood of Our Savior and His Mother, “The work of our redemption began at the moment when the Word descended from Heaven in order to assume a human body in the womb of Mary. From that moment, and for the next nine months, the Blood of Christ was the Blood of Mary, taken from Her Immaculate Heart; the Heart of Christ was beating in unison with the Heart of Mary.”

Jesus Himself said this in an appearance to Sister Lucia, “I want My Church to . . . put the devotion to this Immaculate Heart beside the devotion to My Sacred Heart.”

It doesn’t seem to me that Christ meant that we must include the Immaculate Heart of Mary as part of or alongside any image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. But He desires that we should contemplate the profound role of Our Mother Mary’s Immaculate Heart in her shared suffering with Him, while contemplating the mystery of Christ’s redeeming love. It would be appropriate even if not required to display images of the two side by side.

I’d love to know your thoughts on this and any other points I’ve raised, so please comment!

My Humble Efforts

Ever since the Immaculate Heart of Mary Oratory I attend was first hosted in 2006 at the Five Wounds Portuguese National Church in San José, I’ve particularly admired two in particular out of the scores of more-than-a-century-old stained glass windows there. These two smaller windows of Jesus’ Sacred Heart and Mary’s Immaculate Heart are high up on the walls on either side of the altar. A friend, Jay Balza took photos of the windows, and I used Photoshop to straighten and edit them. I sent the Immaculate Heart of Mary image to Canon Raphael Ueda, when he was first assigned as rector of the oratory, and he still uses it in the bulletin and on posters, as a kind of logo, even though COVID caused our separation from our host church.

I’ve started spending Sundays after Mass painting to use semi-dormant skills I learned getting an art degree in my 30s in drawing and painting. I try to keep doing art, but irregularly. I’m not as polished as those who do art full time, but Sunday painting is a nourishing re-creation, giving my left brain a rest after I write all week. It’s also gratifying that several people who see what I am doing tell me they admire my work. Below is the Sacred Heart Image (cropped) from the stained glass window along with studies I’m doing to prepare for an oil painting that I’m hoping to submit to the Dappled Things competition.

I was also inspired by the idea of contemplating Mary’s Immaculate Heart in relation to Jesus’ Sacred Heart, so I mocked up one image (see below) merging the two images from the windows side by side. I like how the designs fit together so well with the patterns of the acanthus leaves joining in the middle (after a few tweaks I could make). So now my ambition is to paint both images side by side. If I can get only the Sacred Heart image done by the deadline, I will submit that, and then I hope later to do a painting of the Immaculate Heart image to display with it.

Cautionary Examples

In his post about the contest on the Dappled Things website, Bernardo writes,

“Some of the most widespread images present sentimentalized portraits of a Jesus with doe eyes, Pantene hair, and what appears to be rouge on his cheeks, which are at least as likely to discourage devotion as to promote it. The Sacred Heart deserves better, and so do the Catholic faithful who love this devotion.”

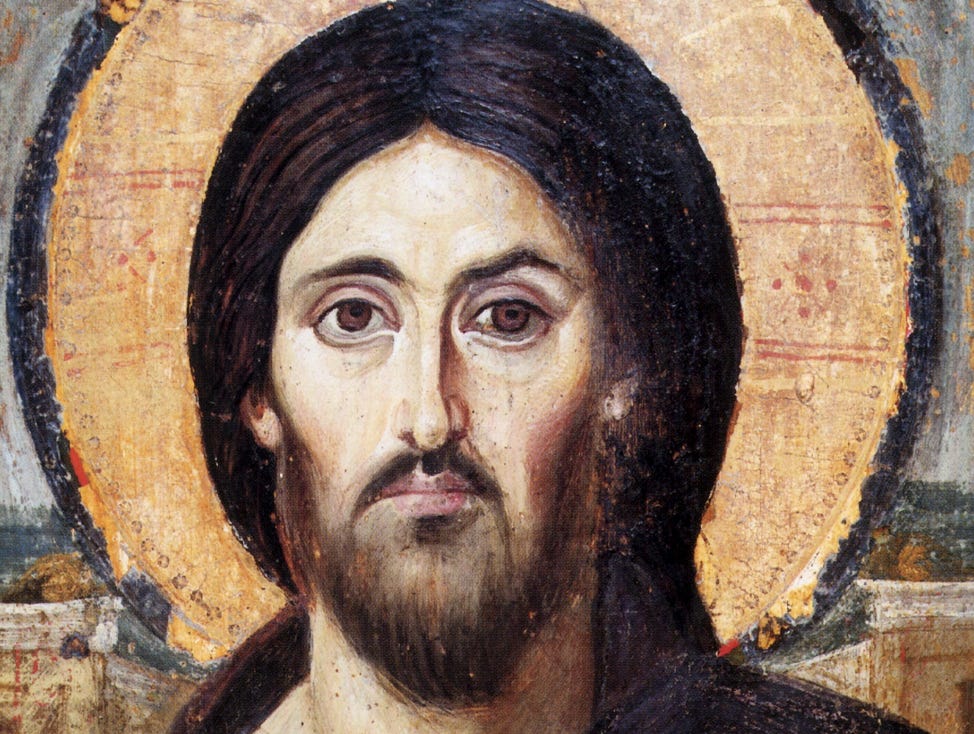

I wrote him suggesting that doe eyes are not always objectionable. The huge eyes in icons are an example.

As one Orthodox writer expresses it here,

“The eyes in representations of Christ, the Virgin and the saints naturally became the focal points of Christian imagery. To put it simply: the meeting of the eyes of the beholder and the eyes of the saints represented on icons was surely one of the primary goals of authentic Christian art.”

Another writer expressed the conventions of portraying the eyes and other facial features this way here :

“The faces of the saints have large, almond-shaped eyes, enlarged ears, long thin noses, and small mouths. Icon painters attempt to indicate that each sensory organ, having received the Divine Grace, was sanctified and had ceased to be the usual sensory organ of a biological man.

Bernardo replied to my question about doe eyes this way:

“This is what I'm referring to, and it needs to stop.”

And I wrote back, “I agree totally.” That was followed quickly by another email from him.

“Oh dear, since launching the contest, now I'm seeing a new kind of horror on Google Images. Pictures like the one below, which are rather obviously AI generated:”

What Does Hilary White Think?

Hilary White, artist and writer, posts at her Substack about “how physical objects of Christian sacred art – icons, buildings, works of art and music – are integrally related to the pursuit of mystical intimacy with Christ.”

Isn’t mystical union with Christ in prayer, above all, what we aim for in our devotions? An image of the Sacred Heart should not be just an accomplished and beautiful work of art to hang on a wall.

Hilary writes about how Western art departed from the rules of sacred art when artists embraced naturalism and perspective instead of using the traditional language of sacred art that had been developed over more than 1,000 years.

I emailed her, “Do you know anything about the history and rules of depicting the image of the Sacred Heart?”

Here is her reply:

“The Sacred Heart is a modern, and very much a Latin/Western devotion, so there are no iconographic rules for it connected to the Byzantine conventions, and no iconographic prototypes. I would only suggest avoiding Western naturalism and in general following the iconographic tradition for depicting Christ. . . . But there's no such thing as ‘historically accurate’ for a modern devotion. Canonically appropriate is a better standard to shoot for.”

Because Western naturalistic art departs from the traditional language of sacred art, she writes, she and others believe it is not fitting for sacred art.

“To people of the Eastern Orthodox or Byzantine Catholic churches, this is not sacred art. It is secular art with a sacred subject. . . .”

“They call its realism, ‘naturalism,’ in the theological sense, inasmuch as it concerns itself not with ultimate, heavenly realities that must be depicted in symbolic visual language - with a very specific vocabulary of colours and forms - but with the things of mere material, physical, natural world. The subjects may be from the bible or lives of the saints, but the style in which they are painted makes them secular. . . . The corruption of Renaissance naturalism has caused western Christianity to forget that ancient sacred visual language.

She continues:

“There are a few sacred artists out there who have taken on the task of creating a Sacred Heart ‘icon’ with these things in mind. . . . A step toward establishing a salutary movement away from that naturalism and sentimentalism that has plagued western sacred art for the last 5 centuries.

“This one, for example, by the English contemporary iconographer Ian Knowles is an interesting example of the kind of "east meets west" idea:”

Knowles paints icons following most but not all of the conventions of traditional Christ Pantocrator (All Powerful) icons. And, as Hilary White wrote me, he does very good work.

A few observations. Following the conventions, Knowles’s Christ is shown with a cruciform halo. The letters “IC” and “XC,” a common abbreviation of the name of Jesus Christ appear on either side of the halo. His right hand is raised in a blessing. His facial expression is stern, to convey his great power.

Knowles shows Christ in red garments highlighted with blue and gold, in contrast to the typical purple or deep blue. He replaces the Gospel book typically shown in Christ’s left hand. Instead, Christ’s left hand points towards a circle containing a heart surrounded by flames. I’ve read that the heart is considered too carnal by Orthodox viewers, which may be why the heart in Knowles’s icon has a more symbolic shape, like a Valentine heart. It is neither red nor representational, and it does not have the typical Western symbols of the crown of thorns, the cross, and the wound from Longinus’s spear. The wound in Christ’s side is shown in gold, and the wound in Christ’s side and in his wrists and and the heart and rays are gold.

At Knowles’s Elias blog, he writes about the creation of the above icon, and I was at first a bit dismayed because of how much the icon was inspired by the work of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J.—whose “cosmic Christ” theology Jacques Maritain summed up once as “Gnostic cosmo-theology of a Hegelian variety.” At the Elias blog, Knowles did note that the icon is not only inspired by de Chardin but also by “the tradition and teachings of the Church.”

Knowles replied this way to an earlier draft of this essay in which I mistakenly identified him as a follower of de Chardin: “I should say that I am not a devotee of de Chardin, but I appreciate some of his insights, and that the brief was from the client to base the image around de Chardin's teaching.” Hmm. I do have to admit I reluctantly appreciate some of Chardin’s insights too.

However, no matter your opinion about de Chardin, the work itself stands on its own to illustrate one approach to developing a new subject using ancient iconographic techniques.

Here’s another icon by New Zealand iconographer Michael Pervan, who writes that “icons are to the eye what Holy Scripture is to the ear.”

Other Interesting Reads on the Subject

Artist David Clayton writes in “Halo! Halo!” at New Liturgical Movement about the “suitability of the iconographic form for a Sacred Heart painting.” He also echoes what Bernardo Aparicio writes with these words: “And I have to say that most of the Sacred Heart images I see are, to my eye, sentimental and unattractive.”

The Vatican Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy provides a great overview of devotion to the Sacred Heart, and it also speaks of “certain over sentimental images which are incapable of giving expression to the devotion's robust theological content or which do not encourage the faithful to approach the mystery of the Sacred Heart of our Saviour.

“Recent times have seen the development of images representing the Sacred Heart of Jesus at the moment of crucifixion which is the highest expression of the love of Christ. The Sacred Heart is Christ crucified, his side pierced by the lance, with blood and water flowing from it (cf, John 19, 34).”

Hilary White, mentioned earlier, writes about Byzantine and Romanesque art and contrasts them favorably with the naturalistic art that became dominant during the Renaissance. As she points out, the cult of the celebrity artist and the worship of the works by these celebrities is, well, not compatible with sacred art.

In the medieval Christian culture, the painter was a craftsman, an artisan, who learned a trade and devoted his life to bringing his skill up to the highest level possible. Paintings were made in churches with the aim of elevating the attention of the viewer to God and heavenly things. In Vasari’s new Renaissance world, one does not use the work of painters as honest craftsmen for the right worship of God; one worships the work itself, and elevates the painter to the status of “artist,” a kind of oracular or quasi divine cultural office. And that, friends, is idolatry.

Her recommendation is for the Sacred Heart of Jesus to be portrayed in continuity with the canons of Eastern iconographic tradition that were also maintained in Italian Gothic and Italo-Byzantine Christian sacred art.

In his essay, “Orthodox iconography versus Renaissance art” Dr. Stephane Rene argues that:

“the movement toward naturalism - the attempt to create an illusion of nature - opposes the Christian traditions of (liturgical) sacred art.”

Iconography, on the other hand, does not attempt to faithfully imitate the carnal body of flesh and blood which is corruptible, but focuses on the transfigured incorruptible body, which it renders according to specific symbolic conventions rather than the imitation of physical reality.

My Western artist friend once complained that she didn’t like icons because nobody looks like the figures portrayed in icons. But the lack of portraiture in icons is intentional.

“[I]n contrast to the art of the Renaissance, icon painting is not illusionist, that is, it does not try to convince the viewer that the world depicted on the panel is real, but, on the contrary, tries to make sure by all the means it possesses, that the represented is unreal, ideal, dematerialized. We cannot diminish the achievements of Byzantine and Russian artists by assuming that they did not know how to paint better. They simply consciously and purposely employed a completely different convention of painting, a completely different artistic language. To be able to appreciate the spiritual depth of icon painting we must learn at least the basic "grammar" of this language. . . .

“The faces of the saints have large, almond-shaped eyes, enlarged ears, long thin noses, and small mouths. Icon painters attempt to indicate that each sensory organ, having received the Divine Grace, was sanctified and had ceased to be the usual sensory organ of a biological man.”—From “Understanding Icons” by Alexander Boguslawski

"Why You're Wrong About Medieval Art" by artist, poet, and hymn writer, Daniel Mitsui, published in Dappled Things was recommended by Bernardo Aparicio. Mitsui argues that the principles of Gothic art are properly traditional and far more suitable for sacred art than naturalism.

“Sacred art has a permanent content that is knowable from tradition. The art called Gothic, which began in the twelfth century, is fully traditional; its makers did not predicate their originality on a rejection of the art of the past. Rather, they put it into order and expressed it more clearly. Gothic art is the visual equivalent of a medieval encyclopedia. It is as complete and disciplined a system as Byzantine iconography, but aligned to the Latin liturgy and the Latin church fathers. This is why I make it the basis of my own artwork.

“I do not think of Gothic as a mere historic style belonging to a certain time and place; that would make it a very boring thing. Rather, I think of it as the best example of an art made according to Catholic principles—principles that are always and everywhere true. They are not merely useful for creating sacred art as it was during certain centuries of European history; rather, they are useful for creating sacred art in any place or time, including our own.”

I took one icon painting course from iconographer Raymond Vincent (you can contact him at Facebook here). In the course, over a few weekends at St. Basil the Great Byzantine Catholic Church in Los Gatos, I learned that icons are created prayerfully to bring the viewer (perhaps you can say the reader) of the icon into the presence of the sacred person or event portrayed.

An icon is written using the sacred language of iconography (with identifying words and features that icon-viewers learn to recognize). There is some disagreement about whether it is more correct to say an icon is written or painted, but thinking of an icon as being written icon neatly ties in with the idea that icons of sacred beings, corporal and spiritual, and of events in salvation history, can be understand only when you learn to read the language in which the icons are “written.”

The icon intended to bring us into the presence of holy person or event when we pray before it.

I’m not totally convinced about the superiority of Byzantine iconography and the Western artistic traditions that follow similar conventions, but I may be getting there.

One closing reminder: This post is not official guidance from Dappled Things about the Sacred Heart Art contest!

Sorry…iconography.

I don’t plan to reject all naturalism or even sentiment if it nurtured our forbears. And I’m a former Protestant.

Thank you.

I found the first half of this piece the most interesting. And I fully agree in my disapproval of the example given for Jesus’ doe eyes.

That said I am glad you are not convinced of the superiority of icon