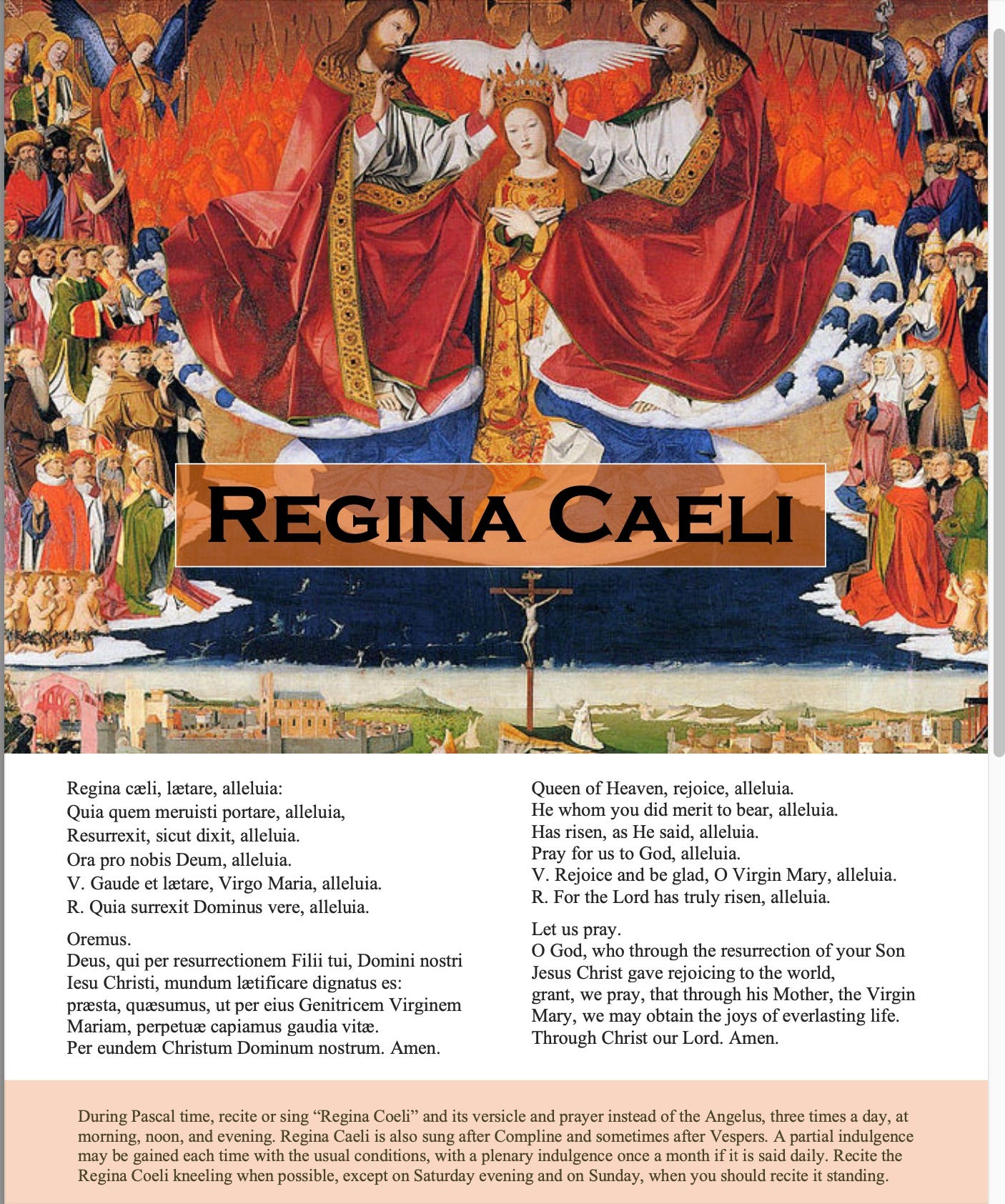

From Easter Sunday until the Saturday after Pentecost, the Roman Catholic Church sings this seasonal Marian antiphon[1] “Regina Caeli” (“O Queen of Heaven).

We joyfully tell Our Lady to rejoice (and we remind ourselves also) because Christ, her Son—He who she alone deserved to bear, is risen—as He said!

Regina, caeli, laetare, alleluia:

Quia quem meruisti portare, alleluia,

Resurrexit sicut dixit, alleluia.

Ora pro nobis Deum, alleluia.O Queen of heaven rejoice! alleluia:

For He whom thou didst merit to bear, alleluia,

Hath arisen as he said, alleluia.

Pray for us to God, alleluia.

At the closing of Night Prayer according to the Liturgy of the Hours released in 1969 and at the end of many traditional Latin Masses, the Regina Caeli ends with the above verses. At the closing of Compline in the traditional Divine Office, and after the Regina Caeli is recited instead of the Angelus during Eastertide, the following versicle and prayer are added:

V. Gaude et laetare, Virgo Maria, alleluia,

R. Quia surrexit Dominus vere, alleluia.Oremus

Deus, qui per resurrectionem Filii tui, Domini nostri Iesu Christi, mundum laetificare dignatus es: praesta, quaesumus; ut, per eius Genetricem Virginem Mariam, perpetuae capiamus gaudia vitae. Per eundem Christum Dominum nostrum. Amen.

V. Rejoice and be glad, O Virgin Mary, alleluia.

R. Because the Lord is truly risen, alleluia.Let us pray

O God, who gave joy to the world through the resurrection of Thy Son, our Lord Jesus Christ; grant, we beseech Thee, that through His Mother, the Virgin Mary, we may obtain the joys of everlasting life. Through the same Christ our Lord. Amen.

Mark Twain Relates A Slightly Garbled Account of the Regina Caeli’s Creation

Mark Twain in The Innocents Abroad (which was published in 1869) wrote a satiric bit that includes the legend of the origin of the “Regina Caeli”—in which he used the alternate spelling “Regina Coeli.” (That formerly common spelling is no longer used in the liturgical books.)

Twain quoted an account from an unnamed book published in New York in 1808, written by “Rev. William H. Neligan, LL.D., M. A., Trinity College, Dublin; Member of the Archaeological Society of Great Britain.” (Since the book isn’t named, I wouldn’t put it past Twain to have made it up.) Twain is poking fun at what he portrays at the incredulity of his real or imagined author, who, in spite of his string of degrees wrote seriously about miraculous occurrences.

Twain wrote, perhaps wistfully: “Still, I would gladly change my unbelief for Neligan’s faith … .

“The old gentleman’s undoubting, unquestioning simplicity has a rare freshness about it in these matter-of-fact railroading and telegraphing days. Hear him, concerning the church of Ara Coeli:

”‘In the roof of the church, directly above the high altar, is engraved, ‘Regina Coeli laetare Alleluia.’ In the sixth century Rome was visited by a fearful pestilence. Gregory the Great urged the people to do penance, and a general procession was formed. It was to proceed from Ara Coeli to St. Peter’s. As it passed before the mole of Adrian, now the Castle of St. Angelo, the sound of heavenly voices was heard singing (it was Easter morn,) ‘Regina Coeli, laetare! alleluia! quia quem meruisti portare, alleluia! resurrexit sicut dixit; alleluia!’ The Pontiff, carrying in his hands the portrait of the Virgin, (which is over the high altar and is said to have been painted by St. Luke) answered, ‘Ora pro nobis Deum, alleluia!’ At the same time an angel was seen to put up a sword in a scabbard, and the pestilence ceased on the same day. There are four circumstances which ‘CONFIRM’—[The italics are mine–M. T.]—this miracle: the annual procession which takes place in the western church on the feast of St Mark; the statue of St. Michael, placed on the mole of Adrian, which has since that time been called the Castle of St. Angelo; the antiphon Regina Coeli which the Catholic church sings during paschal time; and the inscription in the church.”

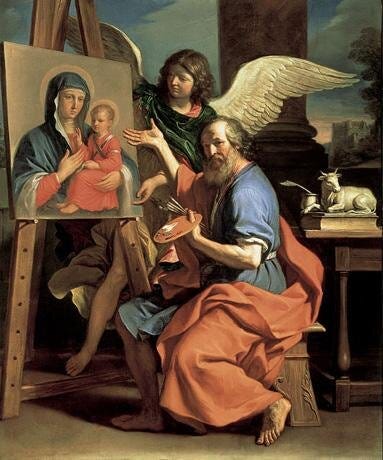

The icon believed to have been painted by St. Luke that was carried by Pope St. Gregory the Great is the image known as Salus Populi Romani, Health (or Salvation) of the People of Rome, which Pope Francis venerated the day after his election and which he continues to visit before and after every papal trip. The tomb of Hadrian became the Castle of the Holy Angel (Castel Sant’Angelo), which later became a residence of the popes and then a prison. The Golden Legend calls it the Castle of Crescentius for a famous Roman aristocrat named Crescentius who was imprisoned there in 974. Castel Sant’Angelo now is a museum, and it is topped by a bronze statue of St. Michael the Archangel sheathing his sword.

The author who Twain quoted was wrong about the name of the church where the image resided. The image was not and is not in the Ara Coeli Church but in Santa Maria Maggiore (St. Mary Major).

Incidentally, Pope Francis was recently quoted as saying that if he ever retires because of health reasons, he plans to live at St. Mary Major as Bishop Emeritus of Rome and hear confessions there.

St. Mary Major as the destination of the procession is corroborated by this quote from Butler's Lives of the Saints:

"The great litany is sung on this day to beg that God would be pleased to avert from us the scourges which our sins deserve. The origin of this custom is usually ascribed to St. Gregory the Great, who, by public supplication, or litany, with a procession of the whole city of Rome, divided into seven bands, or companies, obtained of God the extinction of a dreadful pestilence. … The station was at St. Mary Major's, and this procession and litany were made in the year 590."—Butler's Lives of the Saints as quoted here.

The account Twain quoted says St. Gregory the Great's miraculous procession took place on Easter, other accounts place the procession during Eastertime, and others specify April 25, which is the feast of St. Mark. Even Twain quotes one supposed proof for the miracle that says the procession was done on St. Mark's feast day, without explaining the connection.

An explanation that makes all of these versions of the date possibly correct is that April 25 may occur on Easter.

Dom Guéranger, OSB, wrote in The Greater Litanies in his massive work The Liturgical Year that a procession on which the Great Litanies were prayed was made as far back as the fourth century, and that the procession predated the assignment of that day to the feast of St. Mark.

"This day is honored in the Liturgy by what is called Saint Mark’s Procession. The term, however, is not a correct one, inasmuch as a procession was a privilege peculiar to April 25 previously to the institution of our Evangelist’s feast, which even so late as the sixth century had no fixed day in the Roman Church. The real name of this procession is The Greater Litanies. The word Litany means Supplication, and is applied to the religious rite of singing certain chants whilst proceeding from place to place in order to propitiate heaven."

What the Golden Legend Says

The Golden Legend[2], which was compiled around 1260, relates the story this way. The people of Rome were walking in procession and chanting the litanies to ask heaven to remove a plague that was killing ninety men an hour, while Pope St. Gregory walked with them holding a perfect likeliness of Our Lady that had been painted by St. Luke.

“And lo, the poisonous uncleanness of the air yielded to the image as if fleeing from it . . ..”

Angels were heard around the image singing the first three lines of the Regina Caeli,

“Regina caeli, laetare, alleluia: Quia quem meruisti portare, alleluia, Resurrexit sicut dixit, alleluia.”

Pope Gregory added a fourth line that is slightly different from the version we sing today:

“Ora pro nobis. Deum rogamus. alleluia.”

When the pope then saw St. Michael standing on the top of the castle/mausoleum of the Emperor Hadrian sheathing his sword, he knew that the plague had ceased.

How the Limbourg Brothers Portrayed the Procession

The painting shown below from the precious Book of Hours called Les Trés Riches Heures de Duc Du Berry accompanies the Greater Litany prayer. The Archangel Michael is portrayed as sheathing his sword at the exact moment the plague ended. People in the procession are shown dying of the plague. The Limbourg brothers also all died of the plague in 1416, which is the end date estimated for when this illumination was painted.

Download a Printable PDF

If you’d like to have a copy of the Regina Caeli prayer card shown below for your own use, click here to download a printable PDF.

Listen to the "Regina Caeli"

Simple Tone:

Solemn Tone:

Harmonized by Floriani

From the Floriani About page on YouTube.

Disclaimer: I’ve known and admired Floriani’s founder, Giorgio Navarini, since he was a sixteen-year-old prodigy playing the organ for our oratory schola. “Floriani is a men’s vocal ensemble dedicated to serving the Church and saving the culture through the beauty of sacred music. We believe that dedicated practice of sacred music is an essential element of daily Christian worship, and our mission is to revitalize this tradition in communities around the country. St. Hugh of Cluny once spoke of how the learning, practicing, and singing of liturgical chant is a sure way to grow in holiness, in closeness to the Word, and in submission to the discipline of singing God’s praises. Floriani has taken these words to heart, and it is our intent to inspire and educate the next generation of Catholic musicians in the spirit of this beautiful inheritance. Go to www.floriani.org to learn more about us and support our mission to bring beautiful sacred music to parishes, schools, and homes across America!”

[1] "Marian Antiphons: An Introduction"

[2] The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, Volume I. Jacobus de Voragine. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton University Press. Pp. 173-174.

This article was originally posted at Dappled Things Deep Down Things blog and has been extensively revised.

Absolutely amazing essay on the Regina Caeli! Thank you and God bless!