Robert H. Schuller’s Journey to His Cathedral of Dreams

A book review (outtake from an article about the conversion of Crystal Cathedral to Christ Cathedral)

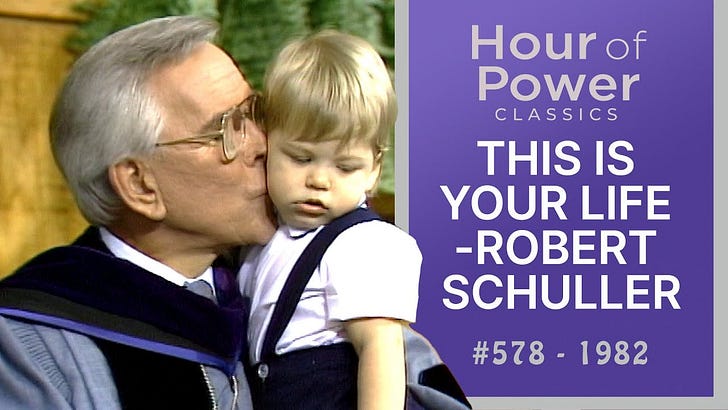

#578 - This is your life- Robert Schuller Aired 11/7/1982

Robert H. Schuller was a tall, effusive, man with a charming smile and a good heart, given to large dramatic gestures in his preaching. You can watch a summary of his life achievements in the above video of a This is Your Life TV show, which was quirkily filmed during an episode of Schuller’s Hour of Power TV show. As the filming shows, his services were more like entertaining spectacles than normal Protestant services. And, of course, they were totally unlike Masses celebrated in Catholic Churches.

As a Protestant from the Calvinist Reformed Church of America, Schuller was not grounded in the sacraments. He didn’t know the purpose of Catholic worship—centered on the Mass's sacrifice. He only knew the Protestant version, with its emphasis on preaching, music, and singing. So the worship spaces he created reflected the Protestant approach, writ large.

Over the course of his career, he grew more and more successful by giving people what they told him they wanted and needed, instead of preaching the Bible or traditional Protestant theology-based sermons. He proclaimed a feel-good-therapeutic message that drew thousands to his services in person and millions to his TV broadcasts at the peak of his fame.

This is a follow-up to an earlier post at this Substack titled, “Can a Protestant Worship Space Be Flipped to a Catholic Cathedral?” —in which I re-published an article previously published in the Spring 2024 edition of Latin Mass Magazine.

As the first part of a two-part series, the linked article examines the remodeling of Crystal Cathedral, which was built for televangelist Robert H. Schuller and converted into Christ Cathedral for the Diocese of Orange in California. It also looks at theories laid out by traditional church architect Duncan Stroik about what makes a work of architecture suitable for Catholic worship.

I am now working on Part II, digging into Reverend Schuller’s ministry and the effects of his gospel of Possibility Thinking on the design of the buildings that are now part of the Christ Cathedral campus.

This outtake from my research for the articles follows the development of the self-esteem-building Possibility Thinking theology of Crystal Cathedral’s founding preacher Robert H. Schuller in his own words from his autobiography, My Journey: From an Iowa Farm to a Cathedral of Dreams. It also shows how Schuller’s idiosyncratic philosophy was expressed in the cathedral’s design.

1926

Robert Harold Schuller was born September 16, 1926, on a farm a few miles outside of the town of Alton in the northwest corner of Iowa. Alton is three miles east of Orange City, which was founded in 1870 by Dutch settlers as part of a New Holland colony. Similar to how Puritans dissenting from the Anglican Church came from England to New England to escape religious persecution, Dutch colonists came to the Midwest under the leadership of dissenting Dutch Reformed Church ministers.

The Dutch Reformed Church had begun as a reform of the Catholic Church, and, effectively if not legislatively, it had become the state religion in the Netherlands. Dissenters sought both freedom to practice what they felt was a purer form of the Dutch Reformed faith, and also to better their circumstances by gaining access to land they could own and farm for themselves. They joined the Reformed Church of America.

Schuller frankly describes himself as a stubborn sweets-loving kid who was so clumsy and inattentive doing farm chores—even though he prayed to do better—that it was evident that his calling lay elsewhere.

“I didn’t mean to hate the smell of the barn or the squish of a cow pie in the pasture. I didn’t choose to be an out-of-place farmer’s son. I just was.”

The Schuller home was built from one of the Sears Roebuck’s catalog’s smallest and cheapest house kits that didn’t include the luxury of an indoor bathroom.

Schuller describes life there with his family of seven in vivid detail: Scorching in summer; freezing in winter; plagued with biting mosquitoes, flies, stinging nettles, and noxious smells; isolated and bored; surrounded by people who he perceived as not having the imagination to dream of anything better. In contrast, Schuller from his childhood onward was full of dreams and imagination to spare.

In 1931, four weeks before his fifth birthday, he receives a message of hope. “I was about to discover the comfort and companionship of a dream.” In “the single most defining moment of my earthly life,” his Uncle Henry, his mother’s brother, who is on furlough from missionary work in China, puts his hands on his nephew’s head, and pronounces, “You will be a preacher when you grow up.”

His uncle tells him he needs twenty years of schooling to become a preacher, then when Schuller starts school a few months later he finds it harder than he imagined. Whenever students are selected during recess to take sides in softball games, he is always chosen last, after every other boy, and girl, in the school.

“I asked my teacher, ‘Why didn’t anyone want me?’ ‘Well,’ she said, ‘You’re very likeable, but you’re . . . well, you’re fat and slow, you know.’”

“Being described as fat as if the descriptive word constituted who I was! . . . I had discovered the power of negative self-esteem.” This moment helped to later inspire his philosophy of preacher as therapist, whose role he saw as making his hearers feel better about themselves.

Schuller studied for the ministry at Hope College and Western Theological Seminary, both in Holland Michigan.

At Hope, he studied psychology, which became a lifelong passion.

And he reinterpreted Calvin’s teachings. He writes that a core teaching of his denomination, the “supposed ‘depravity’ of human beings was . . . a product of Calvinist followers, not of John Calvin himself.” He writes that he also rejected the idea of “Hell (whatever that means and wherever that is).”

He goes on to claim that his “reinterpretation of Calvin’s teachings liberated “humanity from a shaming, blaming, and cowering Christianity, with its railings against the ‘sin’ of pride,” and replaced that view “with a God-inspired drive for self-worth. I didn’t know it then but expounding this liberating force would become my life’s work.”

In another section, Schuller claims “If you read your New Testament as I did, you’ll see, Jesus never called anyone a sinner, His ministry was the teaching of peace, love, and joy.” (Note: It’s so easy to find places in the Gospels where Jesus speaks about hell and sin, it’s hard to imagine how Robert Schuller missed them.)

Somehow his being what he called a theological positivist instead of a negativist would make resistant hearers receptive to the Christian faith. Whether or not his self-esteem gospel ever brought anyone to true faith in the full revelation of Jesus Christ in His Church, it was remarkably successful in attracting people to Schuller’s congregations.

1950

In 1950, Schuller was ordained and married Arvella DeHaan, a pretty and intelligent church organist who became his partner in ministry and the mother of their five children.

When a preacher is offered a position leading a church, he is said to be

“called.” Schuller was called to Ivanhoe Reformed Church in a Chicago suburb. It only had 35 members. Five years later, the congregation had grown to between 400 and 500. (His autobiography gives 500, and his wife in the This Is Your Life show gave 400 as the congregation's size.) A pastor’s success is mainly measured by growth, so it seemed he was off to a good beginning. He found he had a talent for growing church congregations.

He started to visit people in the surrounding area, asking what they wanted from a church, the beginning of his pastoral approach of giving people what they wanted.

He had to relearn how to preach. Even though he’d graduated seminary with a first prize in preaching, people were bored with his intellectual sermons about doctrinal points from the Reformed Church catechism, which were the normal type of sermon given by prechers in his denomination.

Schuller also began to build rapport with non-religious people. He learned a lot from Dale Carnegie’s book How to Win Friends and Influence People and also from The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale: “Within those two books I would find the practical advice I so desperately needed.”

He began by assuming “every person I met had a need to be treated with respect”— which a lot of people need to learn. But then his thinking took a curious direction. “I realized that every sermon I preached (whether formally from the pulpit or casually at a coffee shop) should be designed not to ‘teach’ or ‘convert’ people, but rather to encourage them, to give them a lift.”

Hiring His First Architect and Building Beyond His Means

At Ivanhoe, Schuller had his first experience of hiring a well-known architect not knowing how he could raise funds to pay for a distinctive design. He hired Benjamin Franklin Olson, then regarded as “one of America’s great architects.”

Olson admonished Schuller, “Never compromise on the fine details in design, . . . Art—not money—must have the last word.”

“’But what if you don’t have the money?’ I argued.

“’Broaden your financial base. Raise more money.”

“Sure. Simple,” Schuller thought.

But then a professional fundraiser who worked on a percentage of the money raised, easily brought in enough donations to pay the architect and build a distinctive church. It was simple. Before he went on to other projects, the fundraiser left him a book that planted another seed. The book’s author was the pastor of a “drive-in” church in St. Petersburg, FL. Robert and Arvella had already experienced a drive-in service on their honeymoon when they attended a service at which a Lutheran pastor preached from a snack bar roof at a drive-in.

Schuller was planning to spend his life as pastor of the Ivanhoe church, so he did not foresee a need to apply the drive-in church model, but he was inspired by the author’s “willingness to go to the edge. . . . I had no idea these influences were preparing me for a new kind of ministry in California.”

That new kind of ministry would require a new kind of worship space, and Schuller was learning he could hire the best architects and use various strategies to fund the design work and construction costs for his buildings.

1954

In 1954, Schuller was called again, this time to start a new church in Orange County, California. He was told, “New houses are going up by the hundreds. A guy down here by the name of Walt Disney is building a new theme park just a few miles away. We’re convinced it has real opportunity.”

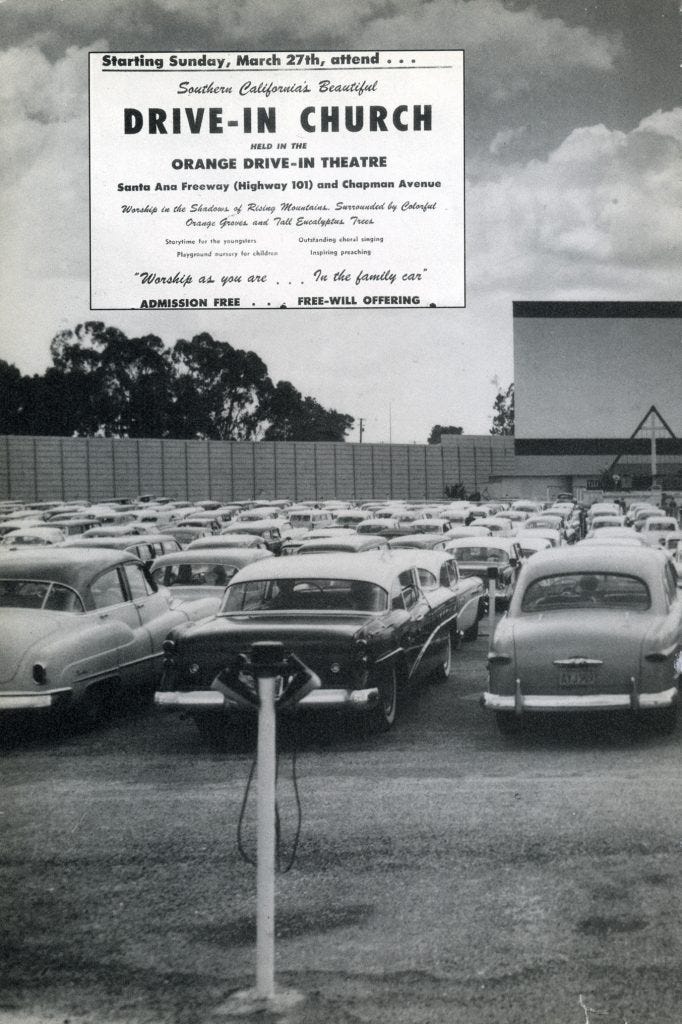

Orange County is south of and adjoins Los Angeles County. Robert, Arvella and their two children at the time rode in on the wave of the area’s post-war influx of families. At first, they couldn’t find anywhere to hold services. As mentioned earlier, Schuller already knew two of examples of ministers preaching at a drive-in, but he never expected to do that himself. The only space he could find was a drive-in in the City of Orange that he could use for $10 a Sunday. The manager joined his congregation.

The car culture was booming along with the suburban population. Schller placed an ad in the local paper. “ Worship as you are in the family car.”

Schuler began to visit this new location’s neighbors to ask what they wanted in a church. After he met an educated woman who never heard about the Old or the New Testaments, he decided not to mention what he called “theology” in his preaching.

He also decided, “This town doesn’t need a Reformed Church. What it needs is a positive-thinking mission that will meet the needs of the people here who don’t go to any church.” As his congregation began to grow, he started the Garden Grove Community Church, leaving RCA out of the name.

Hiring His Second Even More Well-known Architect and Again Building Beyond His Means

When he mentioned to the regional denominational committee that he needed an architect, they told him a dairy farmer member of the denomination would design his building for free.

“I loved the cathedrals of Europe that I’d seen pictured in books. I loved the less imposing but still beautiful church buildings of our own country that showed a commitment to and a love for fine design that honored God. I decided that somehow, someway, I’d find a good architect and pay him myself!” Schuller writes.

Schuller hired Richard Shelley of Long Beach. The building Shelley designed had stained glass windows on three sides. He didn't have to pay for it out of his pocket. His congregation paid the architect’s fee, and a local bank loaned the construction money.

When the congregation then wanted to close the drive-in ministry, Schuller didn’t want to stop ministering to people in their cars. So he preached at the two locations every Sunday, one indoors and one outdoors.

He then felt another calling, this time from God, that he should build the world’s first walk-in/drive-in church, to accommodate a group of people whose preferences had never before been addressed that way: people who were unable or reluctant to come into a church building.

“We sold the beautiful little chapel designed by Richard Shelley . . .. Our profit on that sale confirmed my belief that good architecture is always a good investment.”

Then the Third Building

Schuller’s ministry then purchased ten acres of land three miles away—which was considered to be out in the sticks. The timing was perfect, just before the Santa Ana Freeway was built nearby and land prices doubled.

Schuller hired Los Angeles architect Richard Neutra. Another of Schuller’s non-traditional whims for his drive-in walk-in church was to keep the feeling of being in nature that he had enjoyed when he preached at the drive-in.

In spite of their essential compatibility, it took Schuller a while to agree with this declaration by Neutra: “There will be no stained glass in any of my building designs..”

When Schuller chose clear glass windows that suited his novel desire to bring the outside in, he took another step toward delivering a feel-good essentially doctrine-free and Scripture-free religious experience.

1959

They broke ground in September of 1959 for “a multipurpose building containing a fellowship hall, offices, and Sunday school rooms, the first of four Neutra buildings on our ten-acre garden campus. . . . the first of many architectural pieces of art to be built in the next four decades.” A temporary sanctuary held two hundred worshippers on Sundays, and it had an outdoor pulpit where he would preach at an 11 a.m. drive-in service.

1962

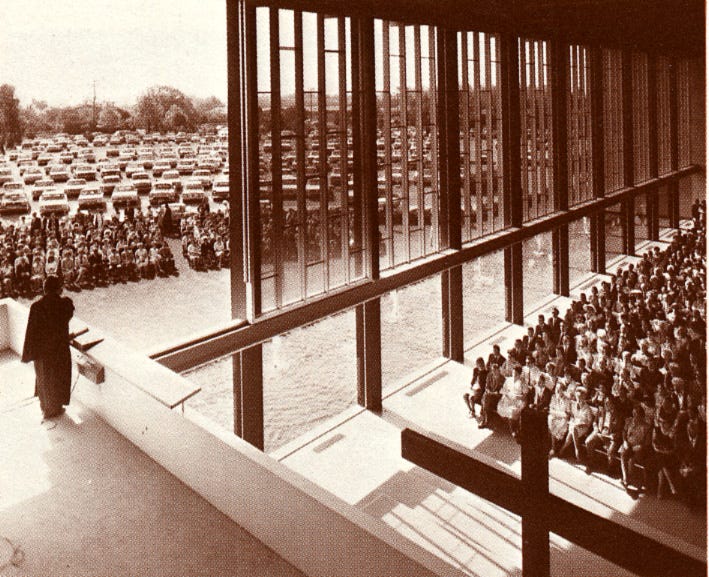

Schuller’s second Garden Grove Community Church was dedicated in November of 1962, This Neutra-designed building called the Arboretum accommodated one thousand inside and another thousand in five hundred cars in the parking lot outside.

Soon they were so full they needed to set up folding chairs outside to accommodate the overflow.

“The glass doors opened at the touch of a button, and left an opening twenty-four feet high and twenty-four feet wide”—for the first time enabling Schuller to preach to people both inside and outside at the same time.

Fountains and lush landscaping were included to make people feel peaceful. Schuller writes, “I had learned, in my more than thirty-five hundred calls on people in Orange County during my first two years in California, that one of the things people wanted was a place of peace.”

Also, Schuller writes “a ‘natural’ atmosphere would be less obstructive to unchurched visitors, many of whom might be nervous around the intensely religious symbolism of traditional church architecture.”

1968

Richard Neutra and his son, Dion, designed a twenty-five-story tower which was dedicated September 18, 1968 as the Tower of Hope. Fiberglass golden bells on the outside were donated by Walt Disney, and they don’t ring.

1970

In February 1970, Schuller began broadcasting on a weekly television show from the Arboretum called the Hour of Power. Arvella became Executive Producer of the show. She chose the music and edited the words of the hymns, replacing “sexist” language and any passages inconsistent with Positive Thinking.

I watched and took the following notes from the above YouTube video of the first television broadcast on Sunday, February 8, 1970. A shot of the twelve outside fountains (one for each Apostle) is followed by a shot of the building framed by oranges hanging from leafy branches. Harp music plays while another shot lingers on the Disney bells on the Tower of Hope.

Inside, Schuller and another minister in clerical robes solemnly climb a long white stairway diagonally up to the pulpit. A small table for occasional communion services is to the left. An enormous organ begins to play while a large choir sings modified words to the hymn “Holy Holy Holy.” A 24 foot square window slides open, Schuller lifts his arms dramatically, and he intones the words that became his slogan, “This is the day that the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it!”

The “Hour of Power” became the most popular religious television program in the U.S.

1973

Even though Schuller preached a new gospel (with a small g) of self-esteem and of Possibility Thinking which departed from the Reformed Church of America’s theology, the RCA leadership was so impressed with the growth of Schuller's ministry they awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1973.

1980

Schuller dedicated his last and most spectacular worship space, the Crystal Cathedral, in 1980. When working on the design with well-known architect Philip Johnson, of the New York firm of Johnson/Burgee, Schuller insisted the building not only should have glass walls but also a glass ceiling. The name Crystal Cathedral was another of Schuller’s whimsical inspirations.

Here are some telling excerpts from Schuller’s “Litany of Dedication” on the day his latest building opened, twenty-five years after the start of their drive-in theater ministry.

“We gather Oh Lord your people of faith to dedicate this Crystal Cathedral. . . . We offer this structure a shining star as an example to the world of the power of possibility thinking. Let it stand as a strong sermon silently speaking to the centuries one single salient sentence, ‘All things are possible to those who believe.’” [Emphasis mine.]

Schuller’s newly composed hymn for the occasion included these words, “Christ, my Savior, help me see/This grand possibility. . . . /People, people, trust God’s dream/That can feed your self-esteem.”

The congregation was made up of well-dressed white couples with a few teenagers. Other children were probably in the Sunday school. As you can see if you look closely at the still from the video of the dedication below, a glimpse of blue sky about 1/3 of the way from the left shows where the ninety-foot doors opened near the pulpit so Schuller could continue his preferred style of preaching to the congregation both outside and inside the building.

1985

In 1985, the Hour of Power hit the two million viewer a week mark.

1987

After televangelists Jim and Tammy Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart were involved in scandals in 1987, Hour of Power’s viewership dropped. Schuller’s ministry was investigated and was found innocent of any scandal, but his reputation was tarnished. “The dynamic years of growth would never return.”

1988

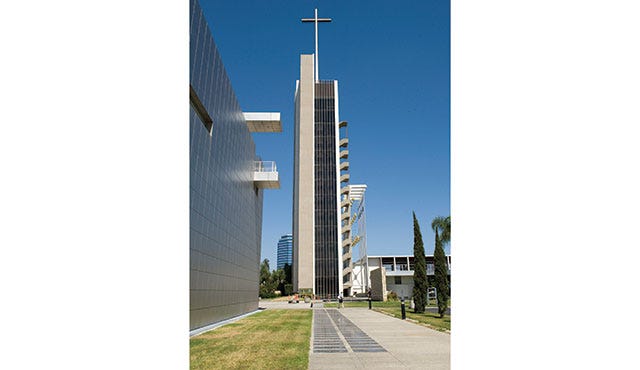

In 1988, Schuller announced his ministry was facing money shortages. But he kept developing new edifices and acquiring more land, until the ministry owned 35 acres full of uniquely designed buildings. See below.

1990

A twenty-three-story bell-tower designed by Philip Johnson was completed in September of 1990.

The same year, a $25 million Family Life Center designed by Gin Wong was completed.

2002

Richard Meier “a third gold-medal architect,” asked to design the $20 million Visitor’s Center, also referred to as the Welcome Center and the International Center for Possibility Thinking. The interior is so futuristic that it was used in the movie Star Trek, Into Darkness, as the Star Fleet command center.

2006

At the age of 80, Robert H. Schuller stepped down from active ministry in January 2006 and left his son Robert A. Schuller to succeed him.

2011

In 2011, the ministry declared bankruptcy, the Orange Diocese bought the campus, and Schuller and his wife quit the Board of Directors.

Schuller’s wife Arvella died in 2013, and Schuller died in 2015.

Coda

Near the end of Schuller’s autobiography, which was published in 2001 when he was 75, he writes: “Building this campus has been at the core of my life’s work for forty-six years. That phase of my life’s work is coming to fulfillment, yet the work will live on, because great architecture ‘says something.’ It’s not just elegant but eloquent. . . . Like a sermon in glass and steel, it uplifts the collective human spirit, and thus it is timeless.”

In Schuller’s own words that are quoted elsewhere in this article, the sermon the Crystal Cathedral speaks is about the power of Possibility Thinking.

When Possibility Thinking Stopped Paying the Bills

Some say the bankruptcy of Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral Ministry was caused by one spectacular and expensive building project too many. Schuller’s decades-long successful formula of borrowing for new construction based on expectations of continuous soaring income failed when the times changed.

Scandals had tarnished the public’s image of televangelism. Besides, the White Anglo-Saxon vaguely Protestant unchurched locals who formerly were attracted to Schuller’s new version of churchiness were aging. And the demographics of the surrounding neighborhoods were changing with a majority of minorities moving in. Young people were either alienated from religion or were finding the flowing fountains and the dramatic feel-good preaching style to be old-fashioned.

When attendance stopped growing and dropped, as did TV viewership, donations could no longer keep up with the debts incurred by the building projects.

Basically, the expenses of keeping the show going and of paying the debts for the latest building of the enterprise were more than the current state of the culture could bear.

From email: Hi Roseanne! Thank you for this. It brings back wonderful old memories. You know my father is a Hungarian immigrant, but I don’t think I mentioned he was a convert to Catholicism, by work of God through the ministry of my very faithful, cradle-Catholic mother.

When I was young, we would watch Dr. Schuller’s Hour of Power on television, often before going to Mass at our Catholic parish. Sometimes, we would go to the Crystal “Cathedral” for live services there. Memories of the Hour dominate my earliest memories of Sunday morning.

When the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, the metropolitan cathedral of the province of Los Angeles (the diocese of Orange is a suffragan diocese) opened, I was the first associate director of liturgy and music (though my official title was “associate director of liturgy,” at least half my work was in music), and for at least two events, if not three, I was privileged to escort Dr. Schuller and Arvela to their seats—the VIP escort. I found him to be a kind, gentle, humble person; his wife, who only came one time if I recall correctly, was charming, kind, and together, they made me feel as if I was an old friend that they were glad to see.

While I know what went on elsewhere, my experience with them was nothing but the best. I know he had decided to sell the CC to the Catholic Church because he knew it would then always be a house of worship; at the same time, when I heard the news, I was working as a parish organist and accompanist in that diocese, and the news was received by all I knew with dismay. The acoustics, the building style, and so much more of what we knew as the “Crystal Cathedral” seemed so very inimical to Catholic sensibilities that we all felt a great disappointment. Then again, what kind of building could they possibly have built? I think it could quite possibly have been worse! . . .

Hope all is well!

S.O.