Ten Commandments Movie, a Tradition for Easter and Passover

For years, the 1956 version was broadcast on TV on Easter Sunday afternoons. Why then exactly? This article seeks out answers to this and other related questions.

The first time I saw The Ten Commandments it was newly released in the movie theaters in November of 1956, and I was 11 years old. The sisters of Notre Dame took me and the others students from Immaculate Conception grammar school in Worcester Massachusetts on a field trip to see the film. Promoted as “The Greatest Event in Motion Picture History,” it was the biggest grossing movie of the year, and it was showing at one of those over-the-top movie palaces that were still found in every city neighborhood and town center in those days. In case you may have never heard of or seen a movie palace, they were often given exotic names, such as the Bijou, or Paradise, or, naturally, the Palace, and they had up to 3,000 seats. A few of these theaters have been preserved. One is the Stanford Theatre in Palo Alto, California, which opened in 1925. It has been restored and kept open by the Packard (as in Hewlitt Packard) Foundation, as a place to see old movies in the style in which they once were commonly seen.

The decor of the theaters was often Egyptian in design, and always spectacular, with some mixture of ornate plasterwork, marbleized columns, mirrored walls papered with brocade, and usually with grand chandeliers hanging in two-story lobbies. Some compared them to churches for the unchurched. Even for weekly Mass goers, the movies were big competitors for minds and hearts. The actors whose much-larger-than-life-size polished and perfected images were projected onto the huge screens were often turned into idols by devotees.

Fr. Michael Morris, OP (2016+) who left a collection of movie posters and other memorabilia that is being curated at the Blackfriars’ Gallery at the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology in Berkeley, California, expressed the religious appeal of movies similarly when he compared moviegoers to “pilgrims venturing into a world of fantasy . . . when the heavy curtain was lifted in the sanctuary of the silver screen . . . light from a tiny window penetrated the darkness and larger than life actors appeared like heavenly luminaries[1].”

Heavenly luminaries? Oh, yes, I see . . . stars.

Over time, many of the old movie palaces from the twenties were torn down or repurposed. Those that survived were often broken up into smaller multiplex-type theaters where we now watch movies without being surrounded by ersatz glamour.

Back in 1956, I and my fellow students all filed into the movie palace wearing our school uniforms, shepherded by the sisters in their black and white habits with rosaries hanging from the belts around their waists. I was too young to draw any conclusions, and I don’t remember being disturbed in any way by the sexual situations and the violence. But from my adult perspective, I’ve never been able to figure out how the sisters could be so blasé about the excesses of the movie, such as the beefcake and the cheesecake, the occasional sadism, and the pervasive sexual tone of the movie. Maybe they didn’t know what they were getting in for until it was too late? Another thought is that they didn’t want to be seen as prudes. Or maybe it was best to pretend not to see anything risque, since they were supposed to be above all that? Besides, it’s a Biblical epic, and evil gets punished in the end, so it must be good, right?

A lot of things are written about Episcopalian Cecil B. DeMile’s contradictory combination of religious fervor and his life of open adultery with multiple mistresses. The Ten Commandments was a lot more tame than his earlier pre-code films, but, especially with the transparent costumes worn by the women stars and by the many dancing girl extras, it’s still wild. People were disarmed perhaps, because it’s a Bible story, and supposed to be uplifting but it is quite steamy, because, ya know, sex sells. In spite of the dancing girls and the bare-chested men, the orgy around the Golden Calf, and the overall suggestiveness, it seems tame now in our even more sexually explicit times and it has a G rating, for general audiences.

It’s not that we are less prudish, I think, but it’s that we have been groomed for more than a hundred years to accept unacceptable things.

Director Cecil B. DeMille had some well-polished rationalizations for the lurid nature of his many Bible epics. DeMille claimed that he had a ministry, and he was more responsible than anyone for leading people to read the Bible. He was also quoted as saying that people who objected to the amount of sex and violence in his movies must never have read the Bible. This, of course, ignores the reality that there is a big difference between reading words that tell about but don’t explictly describe immoral behavior and being immersed in a dark theater for hours watching sensual images played out before your eyes while the action is accompanied by dramatic music.

A Few Specifically Steamy Examples from the Movie

Hulking Charleton Heston, who was chosen to play Moses because of his remarkable resemblance to Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, is practically pawed over when he is a Prince of Egypt by Anne Baxter as Nefretieri, a Princess of Egypt. Later after Moses discovers he is a Hebrew and joins his enslaved people treading straw into the mud to make bricks for the Egyptians, Nefretieri has him taken out of the brick pits, and back in her private quarters, she throws her perfumed curvy self at him some more. And then when he returns as the leader of the Hebrews, she throws herself at him again. But he’s now loyal to a shepherd girl he married after leaving the Pharoah’s court.

Then there is Debra Paget who plays the character of Lilia, a Jewish maiden in love with another example of bare-chested beefcake, Joshua (John Derrick). Lilia is taken against her will from the ranks of water girls by the lecherous overseer Baka, played by Vincent Price. After Lilia is cleaned up, fetchingly clothed, and led in for Baka’s approval, Joshua bursts in and tries to rescue her. He is instead bound and whipped by Baka, until Moses also bursts in, and sets Joshua free. After Moses kills the overseer, Pharaoh gives Lilia as a gift to the traitorous Dathan, a Jewish collaborator, played by Edward G. Robinson.

After the Jews build the Golden Calf, while Moses is away on Mount Sinai getting the Ten Commandments from the finger of God, Dathan offers Lilia as a human sacrifice, while the Jews have an orgy around the altar where she is bound.

I think that’s enough to show you what I mean by steamy.

WIRM

When I was being trained to teach English Composition classes when I was in grad school studying writing in Minnesota, we were told to help students free themselves from writer’s block or from going down ratholes by telling them to write with the acronym WIRM: What I really mean.

What I really mean is this.

St. Paul tells us to only think about what is good, “[W]hatsoever things are true, whatsoever modest, whatsoever just, whatsoever holy, whatsoever lovely, whatsoever of good fame, if there be any virtue, if any praise of discipline, think on these things.” And Jesus told us that whatever we think in our hearts, that is what we are. So, what are we if we ponder sexually charged content or gaze on scantily dressed members of the opposite sex? We have to be careful about the images and scenes we expose ourselves and our children to. What we look at and think about has a lasting impact on our thoughts, feelings, and moral character. Our brains have to process everything we allow our eyes to see and our minds to contemplate.

Innocent souls can be corrupted, and those who have sinned against purity and repented are still vulnerable and should not be exposed to this kind of temptation. And of course we should not pander to the sinful gratifications of those who deliberately seek out that kind of stimulation for their own fantasies. Aside from any spiritual dangers that the viewer experiences while watching provocatively dressed characters engaged in immoral acts, there is another evil to take into account. When we pay to watch this kind of thing, we are paying the actors who are being exploited for their attractiveness. Paying for risqué movies makes us collaborators in a kind of prostitution. It’s only a step above paying to watch pornographic films to watch a G rated film with sexual situations that we as a culture have learned to be blasé about. We are in both cases actually paying a virtual pimp who pays the actors who expose themselves and perform lascivious actions for the camera.

I know a lot of my Catholic writer peers and fellow thinkers believe that we can and even should read and watch evil things and we can do so without losing our souls, but I disagree. I believe that in our culture we have slowly been coerced into accepting previously unacceptable things, similar to the old story about how you can put a frog in a pot, and it won’t jump out if you start with tepid water and gradually turn up the heat until you boil it to death.

Shaming is a powerful tactic. Those who object each time something improper is normalized are accused of being stupid and backwards thinking. Accuse me of being a prude, if you want.

As the common meme I see floating around says: Change My Mind:

How to Watch It, and the 1923 Version Too

Here’s how to watch the movie The Ten Commandments, if you are still interested in spite of what I wrote above :-). Maybe you are immune to the titillation and can just enjoy the spectacle.

For many years after its first appearance on TV in 1975, the 1956 version of Cecil B. DeMille’s movie The Ten Commandments was broadcast on or around Easter Sunday. I haven’t watched TV for decades, so I don’t know how long ago the networks stopped showing it around this time, but this year, only one network, ABC, scheduled it and then only for the Saturday before Palm Sunday.

The last time Stanford Theatre showed the Ten Commandments was in June of 2013.

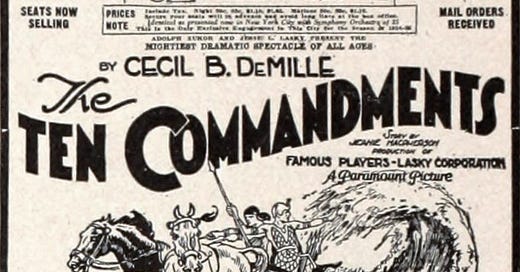

Browsing to see if I could to find the 1956 version available anyplace for free, I chanced across a 1923 version that I’d never even heard of before (that’s the version advertised in the image at the top of this article)—which to my surprise the movie was also directed by Cecil DeMille. I watched that version for free, with ads, here.

It took a while to find, but I was also able to watch the 1956 version here on ABC with many, many ads.

You can buy a boxed set of both movies here

Why this Movie During Passover/Easter?

Why was this movie programmed for broadcast in the Spring around Passover and Easter time?

One obvious Jewish connection to the film is that it is about the intervention of the God of Israel to release the Jews from slavery in Egypt. In the movie and in the Torah, which is included in Christian Bibles as the Old Testament, the Hebrews follow God’s orders transmitted by Moses on the night before the Exodus. Every family or small group of families kills and eats a lamb without blemish, and paints the lamb’s blood on their door frames. The lamb’s blood protects them from the avenging finger of God that kills the first born of every other living being in Egypt that night, even the livestock. That deliverance is reenacted every year at the Jewish Passover dinner.

Of course in Catholic theology, the sacrifice of the innocent lamb and the protection of God’s people afforded by the lamb’s blood is a prefigurement of the shedding of the blood of the innocent Lamb of God, which set mankind free from the consequences of original sin—but that theme is not acknowledged in the movie.

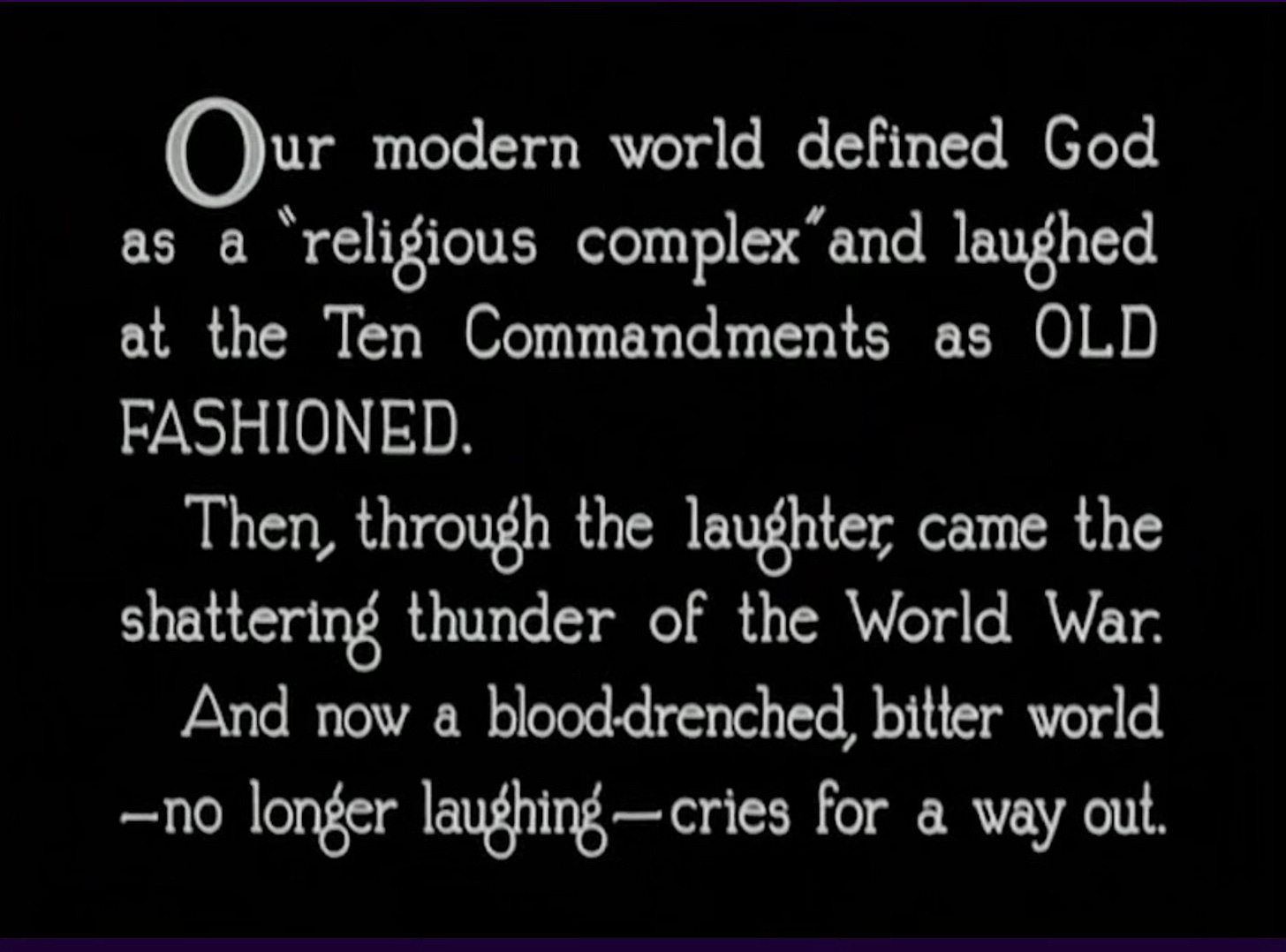

DeMille puts a heavy emphasis on the need for God’s law instead.

The other contrasts between the two versions filmed thirty-three years apart are interesting too.

The movie-making career of Cecil B. DeMilled started back near the very beginning of motion pictures. When DeMille made The Ten Commandments in 1923, it was early in movie history. When he made it again, it was as an all-star, Vistavision epic in 1956, after color and sound were added and after acting styles and filming techniques had greatly changed.

Most of the 1923 movie is in black and white. Although the 1923 version was shot way before color film was perfected, some of the scenes were manually colored using a process called the Handschiegl-DeMille Color technique. For example, the crossing of the red sea had a blue tone and a red tone was overlaid on the masses of Israelites crossing it.

Since it’s a silent film, the story is explicated by intertitles inserted between scenes. Intertiles replaced the earlier practice of having an in-person announcer at each showing.

The 1923 movie did not have a score. It would have been accompanied by music played in each theater where it was shown, probably on an organ.

It was a great success, the highest grossing movie of the year, as was the 1956 version in the year of its release.

The 1923 movie has two parts. The first part shows the slavery of the Hebrews, the exodus from Egypt, the creation at Mount Sinai of a Golden Calf by the Hebrew people while Moses is gone too long getting the the Ten Commandments from God, the orgy that the Hebrews engage in around the calf, and at the end it shows the destruction of those who rejected the God of Israel for the worship of an idol.

After the introductory intertitles, the rest of the first section’s intertitles are excerpts from the Old Testament. The second part of the film is set in the contemporary days of the 1920s when the film was made. Two brothers of a Bible reading mother take two different paths in life, one seeks riches and happiness while rejecting and breaking the commandments. His sins result in the death of his mother; his own life ends with murder and destruction.

One interesting thing for people familiar with San Francisco neighborhoods is that the footage showing a cathedral being built by the bad brother is actually footage of the construction of St. Peter and Paul Church in San Francisco’s North Beach, and the movie also includes several shots of Washington Square Park in front of the church.

What Renewed My Interest in Movie History

My interest in old movies has ebbed and flowed over the years, and until quite recently, it’s been dormant for quite some time. I hardly ever watch movies any more. But my interest in old movies revived in the past few months, because I was invited to write about a collection of rare memorabilia from movies with Biblical themes that is curated by the Blackfriars Gallery at the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology in Berkeley, which I mentioned briefly earlier in this article. I recently interviewed Fr. Christopher Renz, OP, the gallery’s director, about their current show The Spirit of Cinema, and I’ll be publishing an article about that exhibit soon.

In the meantime, you can find out more at the gallery website here. The show is up until the end of May.

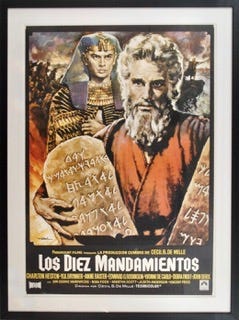

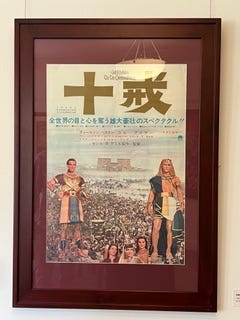

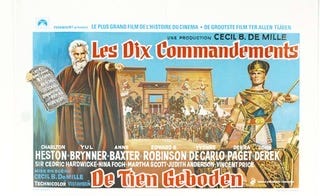

Following are the movie memorabilia from the Blackfriars collection that are connected to the Ten Commandments movies.

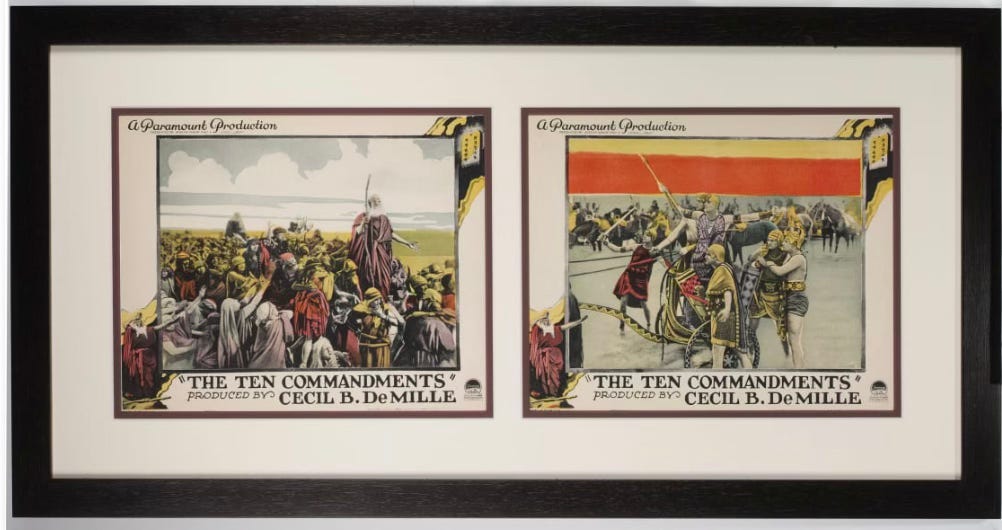

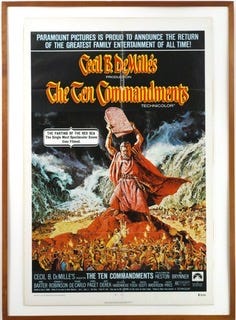

The next three images are lobby cards, which are called Front of the House cards in the UK. They were produced in sets of eight or more. The Blackfriars Gallery has three lobby cards for the original 1923 Ten Commandments movie but no posters from that version. In the early days of movie theaters, posters that were created by stone lithography plus colored, sometimes hand-tinted lobby cards like the ones shown below were sent to the theaters along with the reels of the movie. Lobby cards, 11 x 14 inches in format, show scenes from the movie and often feature the movie’s stars, and are visually framed with information such as the movie’s title, and the names of the studio and director. The posters were displayed out front of the theaters in view of passersby, along with the lobby cards on stands or in niches, to lure customers in.

[1] Michael Morris, OP, The Spirit of Cinema—Illuminating the Bible. The Spirit of Cinema catalog published 2025 by the Western Dominican Province (Oakland). Albertus Magnus Press.

And now for a little laugh. This related cartoon showed up on my Facebook feed this week.

My family loves movies, and these days, we watch a lot of older movies. For years, though, on the weekend before Easter, my family watched both _The Ten Commandments_ and _Ben Hur_. It was our Easter season tradition. My husband and I are the only ones at home now, but we still watch these old movies together just before Easter.

From an email from someone who does not want to be identified:

Wow, what an amazing exploration of "The Ten Commandments"

Just read your Substack reflection on De Mille and his movies. What an amazing amount of research you did! As I've mentioned to you before, you are a great storyteller and, in that sense, a "good preacher" 😇

I appreciate the layered approach to your reflection on De Mille, on the particular movie (Ten Commandments), the movie culture in general, and on the impact of all of it on you both personally and as a participant in the Catholic culture (both as a young girl and now as an adult).

That layering opens up possibility for genuine conversation on the complexity of the cultural aspects of faith, any faith. There are things that "just happen" (the nuns taking you all to see this movie) and then there is the maturation of our personal acquisition of the faith and our reaction to those earlier experiences.

One of the underlying questions your reflection brings up for me is how do we find "the middle way" of charity and compassion both for our "younger self" and those around us who are still finding our way into a deeper and more robust acquisition of the faith. No easy answers but you lay out a helpful framework for a conversation.

. . . I look forward to reading your next "episode"