The marvelous Alice Thomas Ellis in general and Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One in particular

Deliciously sardonic writing from two staunch Catholic authors, one much-better known than the other, but both favorites of mine

This essay is excerpted and expanded from a post I wrote titled Books We Loved in 2019, Part One, which I published at Dappled Things blog. Some Dappled Things editors and contributors wrote about their favorite books at the end of that year, and they asked me to get the round-up started, which I did, with a post from which this is excerpted.

In 2019, I discovered the marvelous Anna Haycraft, whose pen name was Alice Thomas Ellis. It says a lot about Haycraft’s style that the writer of her New York Times obituary “Alice Thomas Ellis Dies at 72; Writer About Spiritual and Mundane” hazarded that Ellis chose her nom de plume because of its hissing sibilants.

As another journalist noted, her writing plowed an “exquisite furrow of black comedy shading into satire.” In many ways, but not all, I see her as a kindred spirit: A bohemian yet deeply devout writer with a dark past before her conversion, she was a lover of domestic life, adorer of her children (she bore seven during her marriage to publisher Colin Haycraft) and of cooking and entertaining. She was quoted as saying that the work she did as fiction editor at her husband’s publishing house and later as a writer was merely part of being a good wife, which she regarded as her vocation, and if her husband did something else for a living, she would be helping him with that.

She was deeply shaken by the death of Joshua, one of her sons, a teenager, who died of his injuries after the roof of a building in a railroad yard collapsed, while he was up on the roof trainspotting. He was not shooting up drugs in the slang sense of the word that became well-known after the movie, Trainspotting. The much-lamented Joshua had simply been practicing the hobby of watching trains (sort of like bird-watching) that had been popular in the UK since the 1940s.

Ellis’s books were widely read because of their excellence and intrinsic interest; even though she was so unabashedly Catholic the headline of her LA Times obituary in 2005 referred to her as “Prolific Author with Staunch Catholic Views.”

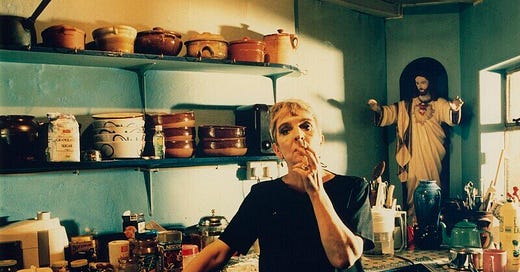

My favorite photo of her that I’ve come across shows her in her kitchen, dressed in her signature black, drawing deeply on a cigarette, with shelves on the sage green wall stacked with pots and pans and bowls, and counters cluttered with cooking paraphernalia behind her. A good-sized plaster statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus with His hands extended in blessing stands in the corner.

As a not-as-prolific or well-known author but one who also has staunch Catholic views, once I learned of her and fell in love with her witty and witchy artistry, I started reading everything of hers I could get my hands on. I know I’m unusual in this, but I don’t buy books as a rule, since I think books—like every other good—should not be accumulated but should be shared. When I do get a physical book, a review copy, for an example of one way a physical book may come into my possession, I like to pass it on for others to read when I’m done. After I read everything by Ellis at the Internet Archive, I went through a lot of trouble to get interlibrary loans of any other books of hers that were available. She seems to have been mostly forgotten, but she well deserves to continue to be read and enjoyed.

In 2022, I learned this good news from Katy Carl, writer, and editor of Dappled Things. Catholic University of America Press is reprinting one of Ellis’s titles, The 27th Kingdom.

“CUA Press is bringing out a series of works by ‘forgotten’ Catholic women novelists—many of whose names you might know for other reasons (Caryll Houselander, Josephine Ward) or who were successful in the mainstream of their day (Alice Thomas Ellis, even Muriel Spark) but have typically been left off academic syllabi and out of the round of reprints at small presses. CUA is bringing them back in a series to restore the sense of their contribution to the overall culture of Catholic arts & letters & I am beside myself with glee.”

I like Ellis’s fiction, especially her first novel, The Sin Eater, better than others of her books that were based on her Home Life columns and better than her non-fiction books, though I am in sympathy with two of her books that painted vivid pictures of some of the deformations of liturgy and practice that she witnessed in the Church and abhorred after the Second Vatican Council: Serpent on the Rock: A Personal View of Christianity, and God Has Not Changed.

In those two books, and in her fiction, Ellis skewered some aberrant post-Conciliar attitudes towards doctrine and liturgy that galled me too. But unlike me, she stopped going to Mass for a long time after it changed. [Actually, I was a fallen away Catholic when the Mass changed in 1969, and when I came back to the Church, I initially accepted the changed liturgy because I trusted the Church—until the focus on the people instead of on the sacrifice of the Mass started getting to me, but I digress.)

Ellis said of one of her characters, Rose, “There was nothing to do on Sundays since the Pope went mad.” No, she didn’t mean Pope Francis. This was 1977, and Paul VI was pope.

“In 2005 she succumbed to lung cancer. A requiem mass was held at the beautiful St. Etheldreda’s in the City of London, a hauntingly moving service in rigid accordance with tradition and marked throughout with soul-stirring plainsong. For those in any doubt, it was a complete vindication of her argument about the proper role of the Church as a place to give solace to the human spirit. She was not a reactionary but rather a woman who recognised the essential truth that tradition is important because it is allied to eternity. Her complexity, her strangeness even, made her, despite her many publicised thoughts, an essentially unknowable woman. I will never stop missing her.”—Deborah Bosley in “The Literary Midwife Round the kitchen table with Alice Thomas Ellis” at the website for the Royal Literary Fund

The Loved One

Speaking of black comedy shading into satire, I re-read Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One again in 2019. It’s one of the few books I’ve read and enjoyed multiple times.

The Loved One is a great satire on British expatriates, the American film industry, our extravagant burial practices for humans and animals, and the absurd romantic fantasies about death that people engage in when they lose track of the realities of the Four Last Things (Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell).

I was led to read The Loved One again by coming across a good essay on P.G. Wodehouse, which was written by the otherwise-loathed-by-me Christopher Hitchens. (I’ve had an animus towards Hitchens ever since I heard him bloviating and character-assassinating Mother Theresa of Calcutta during her funeral procession, when some network had hired him to do color commentary, probably because of his slanderous book about the now-saint called The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice.)

In Hitchens’ refreshingly mostly-unobjectionable-to-me essay about Wodehouse, I learned that Wodehouse had an enormous success writing for the movies in Hollywood starting in 1933 or thereabouts, before he wrote the Jeeves and Wooster books. Hitchens wrote that the Hollywood Cricket Club that Wodehouse helped found was the source for the extremely funny first chapter of The Loved One. (There is a problem with Hitchens’s story though. According to this article “Cucumber sandwiches, Cary Grant and pitch-side glamour: Remembering the Hollywood Cricket Club” that I found yesterday, the Hollywood Cricket Club wasn’t founded by Wodehouse, but by British character actor and one-time England test cricketer Charles Aubrey Smith. Incidentally, Wodehouse didn’t even play cricket. He just took notes at the club meetings.)

The story of what brought Waugh to Hollywood in 1947 is a funny one too. He pretended to negotiate with MGM about a film adaptation of Brideshead Revisited to get a free trip for himself and his second wife, Laura, while being paid $2000 a week (in 1930s dollars!) during the negotiations. The studio refused to see the novel as anything other than a romance, and he was not going to let them film it since they dismissed the religious elements. Its actual title is Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder. MGM was not interested in the Sacred.

While Waugh was in Hollywood, he took a tour of Forest Lawn Cemetery with its founders, got ahold of a book about embalming, and relished the prospect of writing a novella about it all. A Waugh biographer wrote, “As Waugh felt that the eschatological or apocalyptic implications he had intended in Brideshead Revisited had escaped many American readers, he was determined to highlight eschatological aspects of American society in The Loved One.” Eschatological, to save you the trouble of looking it up, as I had to do, means having to do with the ultimate destiny of humanity.

I love how sublimely Aimée Thanatogenos, the main female character, misses the real point of human destiny and just about anything else. Named after famous evangelist Aimée Semple McPherson, her first name is French for “loved one” while her last name is Greek for “born of death.” Her end is both a little sad and very funny. Come to think of it, I once chanced across online an essay a student wrote about Aimée’s vaporous musings before her death, and to my amused surprise, the essayist took them seriously! That was sad and very funny too.

The image is the same book cover that was on the copy I read first when I was 15 years old in 1960. I was in a long-term care former TB sanitarium in Massachusetts recovering from spine surgery, and this is one of the two or three books my sophomore English teacher sent me in a literary care package every week during the ten months I was there. My teacher and mentor Miss Marjorie E. Frye was a creative writer manqué (I recall that she had attended the Bread Loaf Writers Conference), and she was encouraging me to be a writer. Her plan, I think it was a good one, was for me to learn how to write by reading many books by many great writers.

Thanks for the correction. I don't remember where I picked up that error. I guess I needed an editor, which I don't have, never mind not having one as good as she was. Are there any more of the "number of outright errrors" you mentioned that you would care to tell me about?

There are a number of outright errors in this essay. It simply isn't the case that Ellis "began to write" only after her son's death. Her first novel, "The Sin Eater" was published and widely read in 1977, when Joshua hadn't yet even had the accident that led to his death (which occurred another ten months after that).

Additionally, she had published 2 other books (cookery.....but that's still writing) by 1977.

In any case, it's wildly misleading (and weirdly melodramatic) to state that she didn't begin writing until her son died.

This is exactly the sort of "mistake" that Ellis abhored.

Sincerely,

David Terry

www.davidterryart.com