The Seven Sorrows of Mary by Albrecht Dürer

The Church dedicates this month to Mary's seven sorrows. Dürer's altarpiece portraying her sorrows is connected to a Catholic artist, a Catholic ruler, and a Catholic church lost to Luther.

The Roman Catholic Church dedicates an entire month, the month of September, and one particular day of that month, September 15, to The Seven Sorrows of Mary.

September 15 is the Memorial of Our Lady of Sorrows in the new calendar

September 15 is the Commemoratio Septem Dolorum Beatæ Mariæ Virginis (Commemoration of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary) in the traditional calendar

So, this is a good time to look closely at this work of art, “The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin.” In researching this topic, I discovered some fascinating connections this Catholic Marian altarpiece has with the origins of Lutheranism.

This Seven Sorrows of Our Lady altarpiece was commissioned from Albrecht Dürer, by Frederick III, Elector of Saxony (also called Frederick the Wise), after he met with Dürer in April 1496. (You’ll find more about Dürer and Frederick—who I am tempted to redub as Frederick the Unwise—further down in this piece.)

Dürer (and probably his apprentices) began work on the altarpiece around 1500.

Remember that year, 1500.

The altarpiece was part of the interior furnishing of All Saints' Church, which Frederick III constructed starting in 1489 on the foundations of a previous church by that name. The church was part of the new castle he was building in Nuremberg, and it is still popularly called Schlosskirche (Castle Church).

When Frederick founded the University of Wittenberg in 1507, the church served as the university chapel.

The main doors of that chapel are now famous among Lutherans and infamous among Catholics because in 1517, Martin Luther is said to have posted his Ninety-Five Theses on those doors.

Above image: “The Beginning of the Reformation (Oct. 31, 1517)": A small crowd has gathered to watch as Martin Luther directs the posting of his 95 Theses, protesting what he perceived as the sale of indulgences (among other areas of disagreement with Catholic Church doctrine), to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg.

The doors burned in a fire in 1790. Currently, the now-bronze doors on Castle Church are engraved with the Ninety-Five Theses, as they were written in Latin, then the language of the Church and higher learning. They were printed on the university printing press. No copies of the original have survived, but many copies were later made and widely distributed as Luther’s ideas spread. Below is an image of one of the copies.

Initially, Luther didn't intend to start a new religion but to provoke a theological debate. However, as we probably all know, one thing led to another. The previous century’s invention of the printing press enabled pamphlets with Luther’s ideas to be disseminated in a previously unprecedented manner. His ideas were accepted by all classes of people, especially German rulers who wanted more autonomy from Rome.

In 1521, the Pope issued a papal bull that ordered Luther to recant or face excommunication, and Luther responded by burning the bull in a bonfire outside the Wittenberg gates. He called the Pope the Antichrist, and he shouted at the papal bull, damning it to hellfire: "Because you, godless book, have grieved or shamed the holiness of the Father, be saddened and consumed by the eternal flames of Hell.”

Later the Emperor held a meeting in May of 1521 called a Diet in the city of Worms, and at the end of the Diet of Worms, the Emperor issued the Edict of Worms, which declared Luther a heretic and permitted anyone to kill him without legal consequence. Luther’s supporter Frederick the Wise rescued Luther in a mock abduction while he was traveling home from Worms and for his safety hid him in the remote Wartburg Castle, which Ferdinand used as a hunting lodge.

Fast forward a few years. As we all know, Luther’s new religion took hold, in spite of the condemnation by the Pope and the Emperor. Luther adapted the Latin Mass in 1523 to suit his doctrines and then later translated his adapted version of the Mass into German.

He continued to believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but his worship service omitted "everything that smacks of sacrifice" The Lutheran worship service “became a celebration where everyone received the wine as well as the bread.” (Quotations in this paragraph are from the Wikipedia entry on Martin Luther. ) Note that the Roman Catholic Church teaches that Jesus is fully present in both the consecrated bread and wine, but lay people were not allowed to receive both until after the Second Vatican Council.

Skipping forward to the present, now Wittenberg University is a Lutheran university named Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. The Castle Church is no longer Catholic but Lutheran. Sometime over the years, the altarpiece was broken up, one part of it was lost, and the remainder was split between two museums.

More about Dürer, Creator of the Altarpiece, Another Supporter of Luther

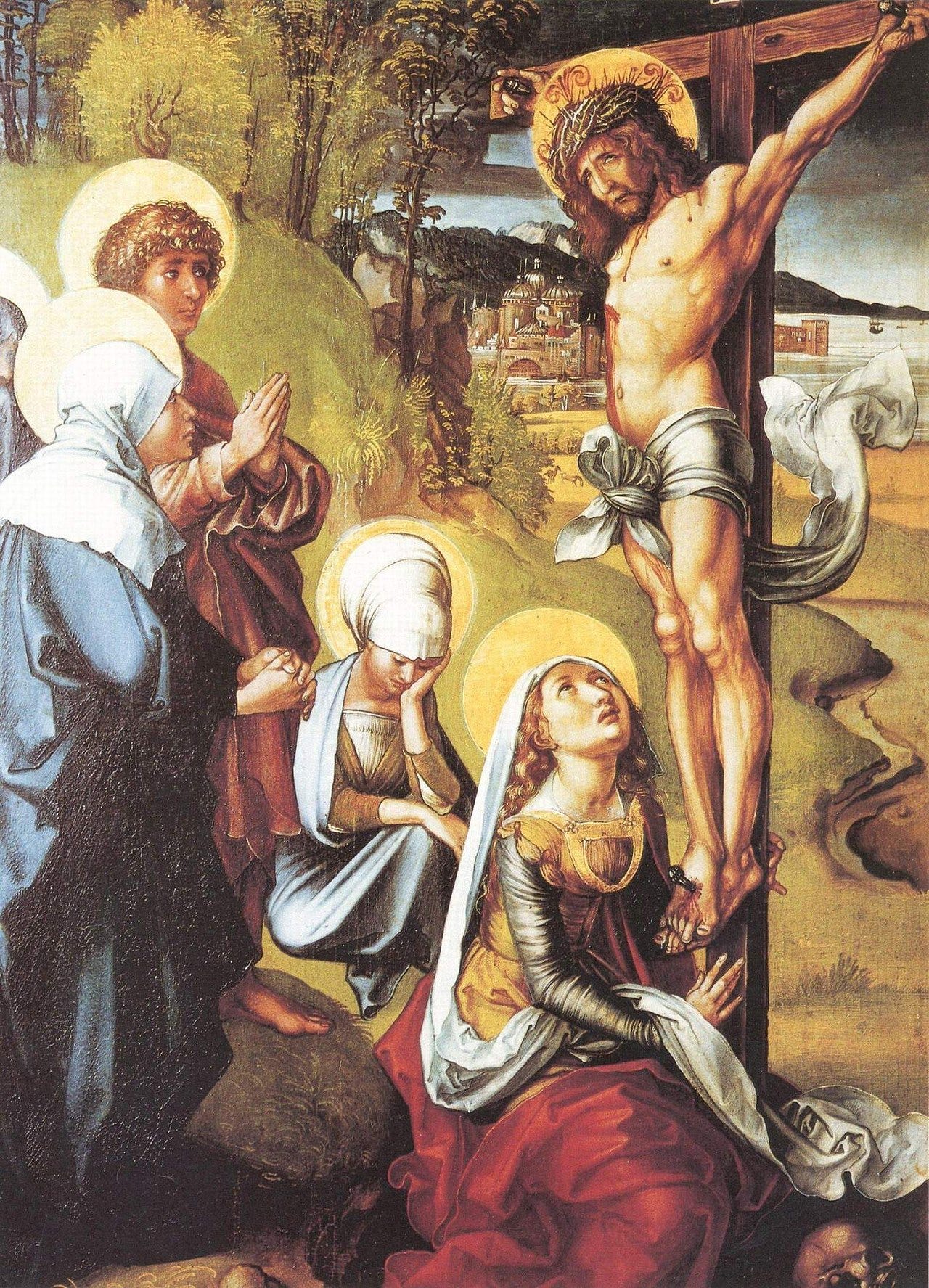

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin was the first known altarpiece created by Nuremberg art prodigy Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)—when he was about twenty-four years old.

Dürer was so talented that he is sometimes called the German Leonardo Da Vinci, and so prolific that the immense total of his paintings, woodcuts, and prints far exceeds Da Vinci’s. In my mind, he certainly was at least Da Vinci’s equal.

I am in awe of the quality of Dürer’s drawings. The following, the first of several self-portraits, done when he was thirteen hints at his future skill. The inscription at the upper right states, "I drew this after myself from a mirror in the year 1484 when I was still a child."

And as good as the drawing and the altarpiece that is the main subject of this article are, his later work got better.

“To get an idea of the volume he created, today we have about a hundred of his paintings, some one hundred engravings, and roughly two hundred woodcuts. In addition, we have over 1,200 drawings, sketches, and watercolors. From these he was most known and renowned for graphic works. These were created from woodcuts or engravings.”—from “ALBRECHT DURER AND THE REFORMATION OF THE CHURCH”

According to Dürer Part 2:The Artistic Adventure of Mankind, for Dürer “one of the main missions of art is the description of Sacred History. In it lied the inspiration for most of his creations. His preferred themes were the passion of Christ and the lives of the Virgin and saints, using engraving as the predominant method for his work. . . . Through engraving, Dürer’s art achieved great influence on his time. Marian themes dominate his pictorial work, covering a long period, from around 1495, with the panels of The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin.”

With the elevated nature of his subject matter and the innovative amount of shading and realistic detail he included, he made printmaking into a fine art. He apprenticed under the first German painter who created woodcuts to be included in illustrations for the newly popular printed books. (The printing press contributed to the dissemination both of artworks and ideas.)

Dürer sold prints from his woodcuts and engravings all over Europe (literally packing his prints with him and selling his wares during his many travels), and they made him both famous and wealthy.

Dürer and his wife ran their printmaking business with the help of apprentices from their home, which is now a museum. You can see a reproduction of a printing press they used to reproduce Dürer’s woodcuts if you ever get there to take a tour.

Dürer was a prime example of the Renaissance artist as rock star idol. In the most outrageous of his self-portraits, which he painted at the age of 28, he portrays his handsome curly-haired self dressed lavishly in clothes made from fine fabrics trimmed with fur, in a frontal pose usually used for paintings of Christ. Interestingly, he painted this self-portrait in 1500, and Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi,” a portrayal of Christ that Dürer’s self-portrait strongly resembles, was painted c. 1500. Who did it first? Did one of them copy the other?

And as I mentioned earlier, Dürer started work on the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin altarpiece about that time.

One important thing to ponder is the audacity of how Dürer portrayed himself like Christ.

Most portrayals of Christ were traditionally close variants of the famous 6th-century icon of Christ Pantocrator that is at Saint Mary of Mount Sinai.

Top (above) Self-portrait (1500). By Albrecht Dürer. At Alte Pinakothek (Old Picture Gallery), Munich Germany. Middle: Salvator Mundi (c. 1500). By Leonardo da Vinci. In a private collection. Bottom: Christ Pantocrator (c. 6th C. A.D.). Anonymous. At Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai.

It took a lot of arrogance for Dürer to portray himself as Christ. Perhaps he shared that type of arrogance with Luther, who he grew to admire. After all, didn’t Luther portray himself as more correct in interpreting Scripture than the Sacred Tradition that had been guarded and handed down by the Church from the time of Christ, more knowledgeable about the teachings of Christ than the Catholic doctors and theologians who came before him, and as having more authority than the Pope?

I always think of St. Francis of Assisi when I think of Luther. When Francis was confronted with abuses, he didn’t start a new religion. He set out instead to humbly become as much like Christ as anyone could be.

More About Frederick the [Un]Wise

Frederick III was a devout Catholic who collected and displayed thousands of relics at his Castle Church, some of which he obtained on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Frederick rebelled against the selling of indulgences to fund St. Peter’s, only because he wanted to keep the proceeds himself. It is said Frederick III protected Luther because he supported a reform of Church abuses, and like many other rulers craving national autonomy, he wanted to limit the power of Rome.

Frederick never publicly renounced Catholicism, even though he protected Luther. In 1525 on his deathbed, he received Communion in both forms, both the consecrated bread and wine, from a Catholic priest turned Lutheran (one wonders about the validity of the sacrament when consecrated by an apostate priest). Frederick was buried in the Castle Church, the same year the Lutheran rite was implemented there, with what must have been his approval.

What Happened to the Seven Sorrows Altarpiece?

The Seven Sorrows Altarpieces is a polyptych, a work of art made up of multiple parts. The central panel of the altarpiece, which depicts the Mother of Sorrows, is at the Alte Pinakothek. the Old Picture Gallery in Munich, Germany.

Unlike other artistic images of Mary’s seven sorrows, there is only one sword and it is not shown piercing Mary’s heart. Instead, it is hovering, poised as if it might be pointing at her heart. Even in this fairly early work, the way Dürer portrays her seems to be affected by Protestant views. It is simpler than most previous Catholic images. Her appearance is rather stocky, not idealized. It has a Lutheran emphasis on the human nature of the Virgin, and it is lacking typical religious attributes, such as a crown. It does have a halo— which he omitted in later images of Mary. The dark, plain background lacks the typical landscapes of the era.

The right half of the polyptych originally represented the "Seven Joys of the Virgin,” but it is now missing.

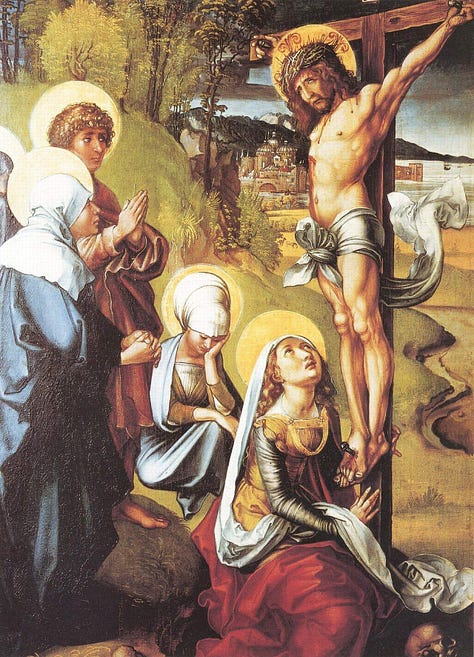

The remaining smaller panels illustrating each of Mary’s seven sorrows are at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Old Masters Picture Gallery, Dresden, Germany. These images in these parts of the polyptych are more typical, but to my eye they seem inelegant, and slightly cartoonish, the colors less harmonious than other similar depictions. In the Flight into Egypt, Marie’s figure seems to be floating over the back of the horse instead of riding it, and in the Via Crucis, Christ’s head is twisted in a bizarre angle.

I cannot find any information about why or when the altarpiece was removed from the Wittenberg Church.

At first, I suspected iconoclasm among Lutherans. Calvin’s followers did condemn and destroy images. But even after Lutherans started holding their own worship services, they initially continued to worship in previously Catholic churches and they didn't destroy the images the churches contained.

Here’s what I think might have happened. A temporary wave of iconoclasm among some of Luther’s followers hit Wittenberg while Luther was hiding in Wartburg. Andreas Karlstadt, a Wittenberg professor and close associate of Luther, had published 121 theses the year before Luther published his 95, and he too was examined and condemned by the Diet of Worms. Karlstadt was somehow able to continue to live in freedom and cause trouble.

While Luther was hiding, Karlstadt published a work titled “On the Removal of Images,” and his followers started rampaging, removing, and destroying religious images until Luther came back to the city in secret and put a stop to the iconoclasm Karlstadt had incited. I think the Dürer altarpiece probably was removed at that time and put into safekeeping to protect it from destruction.

What do you think? Does that sound likely?

In any case, the central panel at some point in the following centuries found its way to a Benedictine convent in Bavaria. After Bavaria was secularized along with the convent, the panel came into the Bavarian National Museum in Munich. As mentioned earlier, it is now at the Alte Pinakothek. the Old Picture Gallery in Munich. As the following text states, the other panels were held at Frederick’s Castle, probably from the time of the iconoclasm onward, until they were moved to the Kunsthammer—which is a collection of mostly scientific instruments founded in Dresden around 1560. They are now in the collection of the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden.

“The central panel, portraying the Sorrowing Mother, arrived in the Bavarian museum from the Benediktbeuren convent of Munich in the early 19th century. . . . The other panels were at Wittenberg, seat of Frederick's castle. In 1640 they were moved to the Kunstkammer of the Prince of Saxony.”

Wonderful post!

“one wonders about the validity of the sacrament when consecrated by an apostate priest”

If the priest said the words “This is my body” and “this is my blood” it was a valid sacrament. Once ordained a priest is a priest forever, even if he is an apostate. He retains all priestly powers.

On another note isn’t it interesting how much money was behind the Protestant Revolution both in Germany and England. Both Frederick and Henry were greedy men who wanted the Church’s money and both remained Catholic until death. Didn’t Our Lord say something about the love of money being the root of all evil?

I so appreciate your love of art and your writing.