They’re Coming to Take Me Away

daCunha.Global, a website with "curated stories," where members could access "beautiful, exclusive, and unexpected stories" for a fee, first published this story. But they aren't around any more.

Somehow, my mother found a new place for us to live that met two essential criteria: she could afford the rent out of the tiny railroad retirement check we lived on after my father died, and the landlord was willing to rent to her as a woman on her own with three little girls who were six years old and under. Our new place was in Jamaica Plain, in another low-rent Boston neighborhood a few miles away from two rooms she had first hastily rented for a few weeks on Dartmouth Place, on the wrong side of the railroad tracks from Copley Square, after she’d spirited us away from our father’s relatives.

This latest move was to the first floor of a house in a private home on Round Hill Street. We shared the house with the landlord. I only remember seeing him once. One afternoon soon after we moved in, he walked in through the front door, looked strangely at my mother without saying anything, used a key to open a door that I hadn’t noticed before, and disappeared up some stairs. My mother looked over her shoulder at the closing door as she was stirring something in a bowl on the kitchen counter and remarked that she didn’t know that he would be walking in on us like that and that he was a weirdo. She began to look for another place.

The move to the house in Jamaica Plain meant I had to change schools once again.

Before my mother had reappeared from wherever she had been and taken us off with her from where we were living with my father’s mother, his sister, and her husband, and a girl cousin who was the same age as my middle sister, I had spent the first part of my first-grade year at another parochial school, Mount Alvernia Academy, in another Boston neighborhood. No matter that we didn’t have hardly any disposable income, my Grandma Sullivan insisted that we all get sent to Catholic schools. God bless her for that. I value the fine education in the basics that I learned from the religious sisters who had dedicated their lives to teaching young Catholics.

Now, after a few weeks in first grade at Cathedral School in the South End of Boston when we lived temporarily on Dartmouth Place, I started going to Blessed Sacrament School in Jamaica Plain.

These kinds of upheavals had happened several times after my father died. We would be living with my mother for a while, sometimes for years, and then she would be gone, and we would live with my father’s relatives—until my mother would come back and take us away again, with or without a screaming fight. I don’t remember how many times this happened. I do remember that nobody ever explained why or where my mother had gone. They didn’t tell kids much those days. And we weren’t allowed to ask questions.

I got to see where she’d gone one time. After one of my mother’s disappearances, when I was around four, my Aunt Peggy, Uncle Raymond, and Grandma Sullivan had packed us four girls into Uncle Ray’s big black Buick, and we went for a long Sunday drive out of the city. After maybe an hour, we pulled into a driveway lined with trees that led to a collection of big, old, red-brick buildings. After we parked, my aunt had lined me and my sisters and my cousin up in our matching dotted-swiss navy blue dresses in a row on a lawn, and we saw my mother looking out and waving at us from a fourth-story window in a five-story brick building. I could hardly see her, of course.

Somebody mentioned contagion, but I was too young to know what that meant or how that applied to my mother, or why we couldn’t see her close up. Later, I heard the family say my mother had tuberculosis, in a tone as if it was a shameful thing. And when still later I got a chance to ask her, my mother protested that the spot on her lung had not been TB, it had been pleurisy. Hard to tell who was telling the truth.

If she was lying, it was probably due to the cruel shaming my father’s relatives brought to bear when they spoke of the disease.

Some sort of kerfuffle happened when my aunt was alone with my mother in her room. The light over the bed was broken. Each of them accused the other of breaking it. We never went back there again.

Those contradictions are the kind of thing that made me always so determined to ferret out the truth. At first, how could I tell which of the family members I loved were telling the truth, and which were not. And later in my life, it became important to know in other relationships, especially when what someone is saying does not add up or when various people’s accounts contradict each other, as they often do.

By the time we moved with Mummy to Jamaica Plain, I was six, my middle sister was five, and my youngest sister was three. My middle sister had previously attended kindergarten at Mount Alvernia Academy, where I had enrolled in first grade, but kindergarten was not available at every school back then. After the move to Jamaica Plain, for the rest of my first-grade year, both my sisters stayed home with my mother while I went to Blessed Sacrament.

I usually walked the half mile to and from school by myself.

I remember waking up for school one morning while everyone else was still asleep. The round, starched, white collar of my blouse still had a gold star pasted on it from the day before, when I had won a classroom spelling bee. One corner of the star had curled up from the collar. I couldn’t get the corner to lie flat again, but I couldn’t find another blouse to wear. I put on my plaid, pleated skirt, and I searched through the clothes on the bedroom floor to try to find a pair of socks, but I don’t remember whether or not I succeeded. I put on a pair of scuffed Mary Janes. I poured myself a bowl of Cheerios with milk and sugar, ate it standing up, and left the house.

About a block away, I knocked at the door of the house of a girl I had met at school to ask if she wanted to walk with me. Her mother let me in. She was making breakfast, and there was a little time left before we had to leave, so she invited me to sit with her daughter at the table. The girl was drinking hot chocolate and eating cinnamon toast, and her mother served me some too. Envy for the comfort and orderliness and the solicitous mother with her apron over her housedress serving breakfast to her daughter struck my heart.

I never did anything with that girl again. They didn’t answer the door the next time I knocked.

Now I understand that most people are repelled by neediness. One reason I expected sympathy as a child is that when my mother went out shopping or to church with us three little girls—we would all be dressed up in our best—she was always angling for sympathy from strangers, so it seemed a natural thing for me to do.

It’s no wonder to me now that she confided in strangers a lot. My mother didn’t have anyone else to talk to besides us.

Her mother had died in 1918 when my mother was two. When I asked, of what? My mother for years told us our grandmother had died of the Spanish flu, and I believed that—until my middle sister Martha got into genealogical research and found Grandma Kaposi’s death certificate, which said she had died of the dreaded and shamed disease of TB.

Mummy was born Martha Gizella Kaposi and raised in Cleveland and was not in touch with anyone she had known there. Her very short but handsome and popular violin-playing Hungarian immigrant father was taciturn and unsentimental with his own family. By the time my mother was a widow in Boston, he lived in Rialto, California, on a rural piece of land, where he was married to his fourth wife, (I remember seeing a photo of him with his thick waisted German wife Christine and some geese on a gravel driveway), and he was no help to us. Her two sisters were married and lived in Indiana and Ohio and kept in touch with only Christmas letters. Long-distance phone calls were a prohibitively expensive luxury. She had a half-brother and half-sister somewhere from her father’s second marriage after her mother died, but they were alienated from their father and from his first set of children. Her family didn’t have money to travel much if at all. For all these reasons and more, she was left totally on her own.

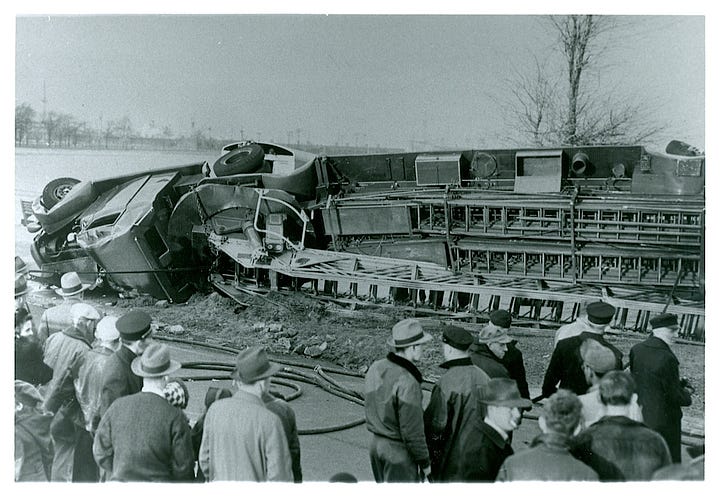

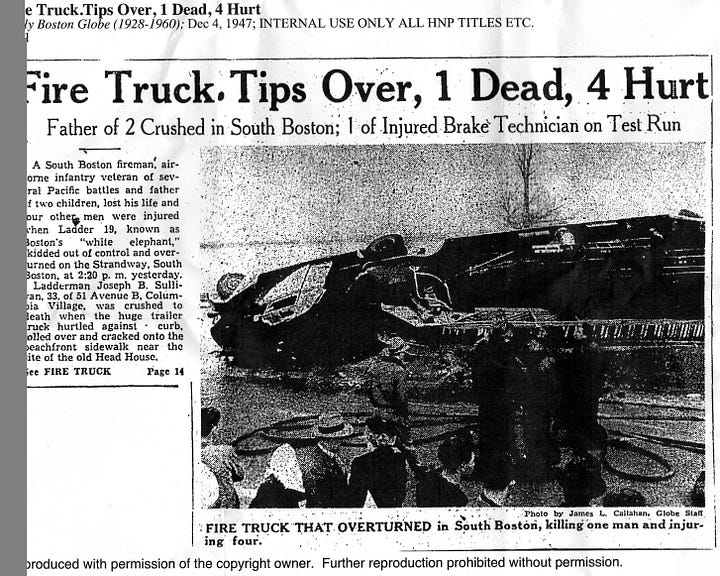

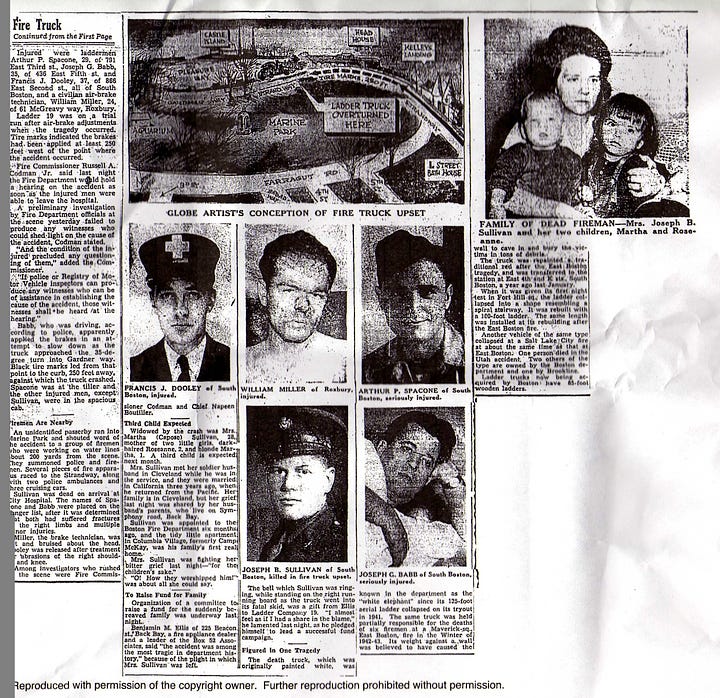

Whenever we passed a firehouse in any neighborhood we were in, if there were any firemen washing one of the trucks or taking a smoke outside in the sunshine, my mother would tell them her story. When they realized she was the widow of Joseph Sullivan, who had been only on the job for three months at the Ladder 19 firehouse in Southie and had been killed in a fire truck accident in December of 1947, she would get a lot of sympathy.

“Oh, I remember like it was yesterday.”

“I lived in Dorchester near City Point when the truck tipped over. I heard the sirens.”

“He was hanging on the ladder on the back, wasn’t he?”

“I saw a picture of you and your two darling girls in the Globe. Some of the fellas came to your place with a tree, didn’t they? just before Christmas? This little one must here have been the one that wasn’t born yet. What’s your name, little girl.”

“Tell the nice man.”

“Joe-anne.”

“Yes, she’s Joe-anne Bernadette. I named her after him. Joseph Bernard. She was born the next month after he died. I tell her they passed each other when he was going up to heaven and she was coming down.”

“That stinking white elephant truck. You think they would have junked it long before, after those four firemen died the first time they used it. That extra-long ladder ….”

I stood at my mother’s side mostly unnoticed while the men told my two blond blue-eyed younger sisters how pretty they were.

I was the dark-haired, brown-eyed serious one whose expression probably never varied much from how I looked in a photo in the Boston Globe that was taken when some firemen brought a decorated tree over to us three weeks after my father’s death. To add to the serious look, I wore glasses from the age of four.

I think I was more than glum because of all the unexplained losses and upheavals. After my father had disappeared (from my point of view) when I was two, my mother kept disappearing and then coming back after years away, and on top of those sad events, my Grandpa Sullivan also disappeared permanently one day when I was five. We stopped at a doctor’s office on the way home from a hot day when he had been canoeing at Norumbega Park and arguing with my aunt, who was in the canoe with him, because he complained of chest pain, and he didn’t come out. We drove home without him, and I never saw him again. As far as I can tell, these things affected me much more seriously than they did my sunny blonde sisters.

The summer after I finished first grade, we moved again. We stayed in Jamaica Plain but moved to a newly built expansion of a red-brick public housing project on Heath Street that was only a few blocks away from the house, and so I was able to keep attending Blessed Sacrament. Then we moved yet again, this time to a second-floor apartment in the same building. Mummy had first rented a two-bedroom on the first floor temporarily because she was in a hurry to get us out of the house with the creepy landlord, and she had put her name on the waiting list for the three-bedroom apartment upstairs. It had come open a few months later.

I don’t remember how my mother managed all that moving by herself. And I don’t know how she got the apartment furnished. She didn’t have a car. I have a memory of her struggling to lug a mattress up the stairs to the new apartment on the second floor and of how my sisters and I tried to hold onto the flopping mattress from behind to try to help her. And I remember then seeing her make another trip upstairs to bring up a metal bed frame while we helped a little by carrying bed boards.

The next summer, at the end of second grade, I remember walking home crying because the school year was over. I loved school and my teacher, Sister Veronica, whose kind, interested face beamed out at me through the frame of starched white cloth (now I know it’s called a whimple) around her face.

School was just about the only interesting thing in my life, besides Sunday Masses at the beautiful Blessed Sacrament Church. Nobody we knew had television yet. At home, my mother took to her bed a lot, smoking, snacking on bagged candy, and reading women’s magazines, the newspaper, and mysteries and historical novels she took out of the library. She more or less fed us and kept up with the laundry, ironing and starching our uniform blouses, changed the sheets, and did other housework, but when she ran out of energy and had to go lie down, as she often did, things got chaotic.

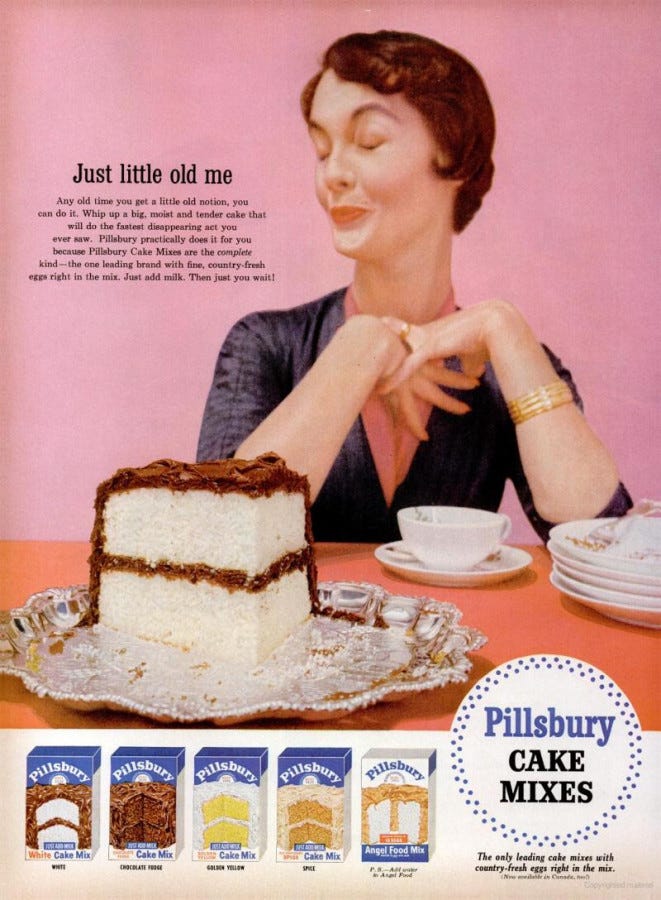

She loved to try recipes from her women’s magazines and to bake, mostly cakes from a mix. She let me bake a cake one day. She was nearby but didn’t watch everything I did while I imitated what I had seen her do. First, I traced the bottom of a cake pan onto waxed paper with the tip of a knife, cut out two circles, put them in the pans, greased the waxed paper and pan sides with Crisco, and then floured them, tapping the pans over the flour canister to get the excess flour off. I preheated the oven, mixed the ingredients in order from the recipe on the box, poured the batter into the prepared pans, tapped them on the table to get rid of any air bubbles, and put them into the oven.

When the oven timer rang, the cake was evenly risen and perfectly browned. After a toothpick I stuck in the middle of both pans came out clean, I cooled the cake in the pans for the prescribed amount of time, then turned them out onto a rack. My mother came over to admire my proud creation.

Then she looked up and noticed something. “Where are the bottles I had on the window sill?”

Earlier that morning she had mixed powdered starch with water for ironing, put the white liquid in some empty milk bottles, and put them on the windowsill behind the sink.

My sisters were playing together in an empty cardboard box. They always played together and left me out, for some reason I still don’t understand. When they realized what had happened, they looked up and laughed at my crestfallen expression. My mother told me, No, we can’t eat it.

She stacked the unfrosted layers on a cake stand and put it on display in a glass hutch in the living room, while mollified my disappointment a little bit. What I had done that day, mixing liquid starch instead of milk into a perfect but inedible cake, became one of our family stories.

I was already reading anything I could get my hands on. I easily picked up new words from context. At school, reading in the easy-peasy second-grade reader about Dick and Jane at the Sea Shore made me realize that some children live in a family with doting parents and older relatives who summer at a beach cottage with a front lawn edged with flowers and spend their summers playing lovingly with each other and their animals, picking up sea shells, and playing in the ocean waves.

One gloomy afternoon, I remember walking out into the backyard of that house we’d lived in before the project, by myself, as I usually was. I looked around at the patchy, weedy dirt patch, and wished I could find fairies hidden under flower leaves, like the ones in a fairy tale I had just read. But there were no flowers there. Or fairies.

I didn’t realize until years later, when I took LSD the first of maybe three times at the age of eighteen, that I’d lived my life in a mostly colorless world, except for the vivid glimpses of other ways of living I got in the stories I was reading, and except for some of the times I was able to participate in the alchemy of cooking.

The next day after my first LSD trip, I was walking on a sidewalk near the shore of Newport Sound. In spite of all the litter around the beach from the Folk Festival from the night before, I was struck by the greenness of the grass, the blue of the sky, and the warmth of the summer breeze, which I hadn’t noticed at all the day before.

The intensity of that brief post-LSD moment jolted my memory back in time to where I was standing on a sidewalk outside the Heath Street project as a seven-year-old and hearing and feeling more than seeing an enormous truck go by. I remember the shock wave as the truck lumbered past, the heavy metal clunk as one of its tires hit a pothole, and the clanking sound as the truck rumbled on down the street. But I would not have been able to tell you the color of that truck or anything else around me to save my life.

Before the end of the summer of 1953, the year I turned seven, a terrible thing happened that made my life more vividly dramatic for a day, sort of like how a deadly storm at sea would be both interesting and horrifying in retrospect if you were a survivor and had lost a loved one when the ship capsized. This time my mother didn’t disappear like Mary Poppins, as she had done the other times she had gone away. This time I, at least, got to see where she went.

It seemed to my mother that something was wrong when we came home one Sunday evening from a long ride on buses and trolleys after an afternoon at an amusement park where she had been able to afford to let us take only a few rides. When she opened the door, she said she knew someone had been in the apartment, but I didn’t believe her. I don’t know why I was suspicious of things my mother said, even at such an early age. I think I picked that up from my father’s family. She told me she had put a thread on the door lock, and the thread was gone. She might have gotten that idea from one of the mystery novels. I was only seven, but even then her precaution didn’t seem normal to me.

I loved my mother, and I had never heard the word paranoid, but I thought that was what she was being. As it turned out a few days later, I found out to my great sorrow that I had been wrong, and she had been right. Something had been up.

I have to mention here that all the doors in the hallways at the housing project were painted a uniform forest green. But not ours. The door to our apartment was blotchily painted pale turquoise-green. And that was my fault.

A few weeks before our trip to the amusement park, my mother had started to paint the living room walls a cream color she said was Oyster White and the baseboards a pale turquoise named Aquamarine Blue. My sisters and I had been “helping her.” But then she suddenly needed to lie down. When she went into her bedroom, my sisters and I took over. A paint can got knocked over, my littlest sister started skating back and forth across the floor on the wet paint, and my middle sister joined her.

I decided we shouldn’t waste the paint, so I tried to be mother’s little helper again, and I started painting the inside of the front door aquamarine as far as I could reach. Then I somehow made my way up the ladder with a paint can and brush and put the can on the shelf at the top, and I began to paint the top of the door. When the aquamarine paint dripped down the outside of the door in glaring contrast with the forest green, I tried to fix it. I went out into the apartment hallway and painted the outside door all over to match the dripped paint as high as I could reach. I stopped when I realized that just made it look worse, cringingly worse.

When my mother emerged from her bedroom again, she just stood stock still and stared. The spilled paint made a long cream-colored streak on the linoleum living room floor, and cream and turquoise spatters were everywhere. Turquoise and cream footprints made their way over the carpet rolled up in the middle of the floor and continued into the kitchen and down the hall to the bedrooms and the bathroom.

I had left the apartment door open, and so she also was faced with a crowd of neighbors who were gawking at us from the outside hall. I don’t remember what she did after she closed and locked the door and connected the chain lock. She never yelled at us when we were little. And she never hit us. I think she was so overwhelmed that she simply couldn’t say anything. It was way before acrylic paints were available. You needed turpentine to clean up paint those days. She began to tidy things up. It took days.

Another thing that may have made her suspect something was afoot is that a few days after the paint spill our tall, dark, and handsome Uncle Ray had come to visit. My mother was at first taken aback to see him at the door because when she had moved with us to Jamaica Plain, she had not given Aunt Peggy and Uncle Ray our new address. I found out much later that we were living only a few miles away from where they lived. The city of Boston proper is big and densely populated, and it was her fond hope we would not be found.

To my surprise, the visit seemed to pass uneventfully enough with no loud accusations and no screaming scene. They talked and smoked and drank coffee for a while in the living room. He pressed money into her hand when he stood up to go. After she let him out through the streakily aquamarine-painted door, she said, “He wishes he had married me.” I don’t know what gave her that idea.

Maybe she was trying to account for him coming to visit and being nice to her. Now I believe the truth was is he was actually on a reconnaissance expedition.

A few mornings after we came home from the amusement park and my mother had thought someone had been through our apartment while we were out, she looked out the window after breakfast, and she saw some cars pull up into the parking area, and something she saw made her tell us that they were coming to take her away. I didn’t hear her say who “they” were, or where they were going to take her.

Some of the cars were police cars. My mother ran to the apartment door, turned the lock in the door handle, and made sure the chain lock was latched.

I started boiling water on the stove. I think I must have read a book about a siege, because I thought we should pour boiling water out the window on our enemies like the defenders of cities used to pour boiling oil on attackers.

It makes me sad to remember how eagerly each of us little girls innocently took forks out of the silverware drawer to stab the bad guys who were coming to take our mother away. Mummy didn’t encourage the boiling of the water or the idea of using forks as defensive weapons. But she was too distracted to stop us. She had only a few minutes to think of what to do. We helped her drag the couch in front of the door to barricade it.

When my mother wouldn’t answer the knock on the door, someone, I think it may have been the building manager, opened it, probably with a master key. A policeman broke through the chain lock. Four or five of them pushed in through our pitiable barricade, and they stolidly ordered my mother to come with them, with no explanation why or where they were taking her.

When she refused, four of them picked her up and carried her down the stairs. She didn’t resist or say anything. I think she was doing her best to avoid showing any emotion that would make them label her as some clinical version of crazy. In later years, she told me that when my father’s relatives had her committed before (“They wanted to steal you kids away from me”) if she cried, the psychologist labeled her depressive and if she tried to put a cheerful face, they labeled her manic.

This may seem hard to believe, but I am not making this up: during those years anyone could sign anyone away for thirty-days observation in a mental hospital. I know it for a fact because, to my present shame, I signed my mother away about nine years later myself, when I was only sixteen years old.

I asked her once if she ever had therapy while she was in one of the state hospitals. “Once in a while a psychiatrist would walk through the ward.”

The seven-year-old me that day in the housing project followed the policemen carrying my mother down the stairs. I was trying to stab one of them in the back through his heavy wool uniform with my fork to try to make him let go of her.

The stairs were crowded with neighbors jostling each other to get a good look. It was as if she was being carried through a gauntlet being stripped naked and being beaten by their stares. I could feel her embarrassment because she wasn’t dressed to go out in public. Her hair was mussed. She didn’t have any makeup on. She was wearing shorts; her legs were bare. And what was most embarrassing for some reason was that she wasn’t wearing any shoes.

At the foot of the stairs, the policeman who I was ineffectually trying to stab patiently disarmed me of my fork. I was surprised he wasn’t angry or rough. My aunt and uncle appeared outside the door. I vaguely remembered later that my two sisters went into their car.

I shouted, “I want my mother,” and I kicked and pummeled anyone who tried to make me leave with my sisters. I stopped fighting only when the policeman I had been stabbing told me I could come along.

He opened the back door of a black paddy wagon. My mother got up the step and sat on one of the slatted benches that lined both sides. I tried to follow her in, but he gently held me back by the arm.

They closed the door, put a bar across it, and locked it. Then they brought me into the front seat with them. They called into the station on the crackling police radio as they pulled away.

I don’t remember the two big Irish cops saying anything to me on the drive out of the city. I could feel they were sad too. It was probably not easy for them to drag a young widow away from her kids and heart-wrenching for them to see me so upset.

After a long ride, maybe an hour, mostly along rural roads, the paddy wagon drove up a hill to a group of large brick buildings surrounded by wide expanses of open fields, woods, and a clear blue sky decorated with puffy clouds.

One of the policemen walked me up the set of stairs and past the columns at the front entrance and through the front door of the main building, and he explained to a woman at the front desk why I was there. She took me to an empty examining room and sternly told me to wait.

I sat there a long time until the policemen came to get me again. They had tricked me again. I hadn’t gotten to go with my mother. I didn’t even get to say goodbye to her.

On our way out of the hospital, the policeman took me past a room where I caught a glimpse of my mother through an open door. She was sitting slightly slumped on the edge of a leather-covered examining table, silhouetted against the light filtering in through the mottled privacy glass on the bottom pane of the high-sashed wood-framed window. She could have been modeling for a painting of a woman without hope, a woman who had her children and her freedom forcibly taken away from her, not for the first time, a woman who was absolutely alone in the world. She didn’t see me as I was ushered past the door.

That was the last sight I had of her for about three years.

And then the policemen took me out the front entrance, down the wide steps, and back into the paddy wagon. We started driving towards Boston through the countryside again, which was all lit up by the sun on that beautiful summer day.

The cops tried to cheer me up on the way back to the city. To amuse me, they turned on the siren when no cars were around on an open stretch of the road. When I pointed at the pretty blue and white and yellow wildflowers growing on the side of the road, they pulled over and told me I could get out and pick some. I was happy to have the chance. We never had fresh flowers at home, and none of the places I’d lived had a yard. I used to look enviously at photos of gardens in magazines and at flower arrangements in rich people’s homes in the movies. There’s that vice of envy again.

When I got back in the front seat with my little bouquet, one of the policemen asked me if I ever held a buttercup under my chin to see if I liked butter. I had never even seen a buttercup. He held one of the buttercups’ shiny yellow cups under my chin. When it reflected yellow against my skin, he said that proved I liked butter. I did like butter. I thought about how my mother always boasted that she didn’t buy margarine, only butter was good, and I got sad again.

In a small town about halfway back to Boston, they parked and brought me into a little corner store and asked if I wanted anything. I asked for a chocolate-covered ice cream, and I asked them to buy some for my sisters too, and so they did.

By the time I finished my ice cream, the other two bars were melting in the paper bag, and I was still hungry. I hadn’t eaten that day, and it was now midafternoon. The cops told me I should eat the bars they had bought for my sisters so they didn’t go to waste. And so I ate the melting bars, embarrassed because the softened vanilla ice cream dripped onto my clothes, and pieces of the chocolate covering broke off and stuck to my hands. I put the wrappers and wooden sticks back into the brown paper bag and tried to clean up by wiping my fingers on the outside of the bag.

I still feel as if I betrayed my mother that day. I let myself be distracted by the beautiful sights, the fields, the little clumps of woods, the ponds, the horses, and the cows. The blue and yellow and white wildflowers. The kindness of the two policemen to me. And the ice cream.

My flowers wilted by the time we got back to the city. We pulled up in front of a red brick and brownstone apartment building on Symphony Road, around the corner from Boston Symphony Hall, in a once-and-future-upscale neighborhood where rents were cheap enough for the working class when I was young.

The policemen rang the doorbell, and when the main door opened they brought me upstairs to the second-floor apartment on the right of the stairs. They stood awkwardly in the front room my family called a parlor, talking for a few minutes with my grandmother and politely avoiding looking too pointedly at my curvy Aunt Peggy, whose red hair was “set” in pin curls held with bobby pins. (We never thought it odd for years that she would always curl her hair, do her make-up, and put on her nylons with decorated seams and high heels before she went to work on her night shift job sterilizing surgical instruments at Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, but that’s a mystery that could be considered another day in another story.)

My sisters and my girl cousin stood peeking around the parlor door. After the nice policemen handed me over to my father’s family again, no one in the family said anything to me at all.

After a while, I slipped back into the routine of living there. But I never stopped waiting and longing for my mother, until she appeared again.

But that too is a whole other story.

***

From an old friend, AM: Hi Roseanne,

Wow - this is an amazing story and I truly enjoyed reading it. You are an excellent writer. I would love to read more of your work and I subscribed to all of your publications.

Thanks so much for including me in this! Would it be okay if I also share it with my aunt, who also loves writing?

God bless you . . .

An excellent read. Very well written.