Seventy-seven years ago, December 3, 1947, my father was killed in a firetruck accident

His death is one sorrowful part of a larger story about my parents and many others like them marrying and raising families at the end of WWII

Sometime in 1944 or early 1945, my second-generation Hungarian-American mother, Martha Gizella Kaposi, met Joseph Bernard Sullivan, my second-generation Irish-American father, in Los Angeles, California. He was thirty and she was twenty-three. At five feet two inches tall, she was a foot shorter than my father. She liked to brag later that she "caught" a tall man. Her own father was about five feet two or three inches tall. She told us that because her whole family was so short her two sisters made fun of her for being a giant—at 5' 2"!

My dad was a private in the now defunct U. S. Army Air Core, and he was in LA when they met, even though it would be almost a year before the war with Japan would end on VJ day in September 2, 1945—because he been sent back from the South Pacific to recuperate in an Army hospital. He’d caught jungle rot like many others soldiers and sailors who fought in the swampy jungles of the Pacific. He must have had a horrific case of it in order to be sent back from the front to a hospital in LA. Here is a telling sketch called “A Friend in Need” by Kerr Eby I found at a Naval History and Heritage website: "In this charcoal sketch, a Navy Corpsman treats one of his Marines for jungle rot in a rudimentary frontline aid station."

Soldiers and sailors would get the disease from not being able to stay dry in the jungles. They'd get it almost anywhere, on the trunk, thighs, face, scalp, on the crotch, under the arms or on the rear end. It was painful like an inflamed case of athlete’s foot. My mom mentioned dad had sores on his back. She didn't specify which area of his back.

I believe my father met my mother when he was on a weekend pass from the hospital, so he must have been feeling better. They met at a bar. She was there with some fellow-office workers, and he was with some other soldiers.

My mother was a slender and stylishly dressed twenty-three year old brunette office worker with nice legs who’d gone to business college in Cleveland after high school. She had moved to California at her father’s invitation.

Her father's name was Joseph too. When Joseph Kaposi first came to the U. S., he joined many fellow-Hungarian immigrants in Cleveland. Her father was handsome and well-liked, played the violin at Hungarian gatherings, and worked as a carpenter. Some time in the 1940s, my grandfather-to-be had left Cleveland for the L.A. area and began to work building Hollywood movie sets.

My mother’s mother, Yolanda, who was also a Hungarian immigrant, had died when my mother was two. That was grief enough, but then her father put her and her two sisters in an orphanage because he couldn’t take care of them on his own. After he remarried, Magda the new wife was reluctant to take on the responsibility of raising her new husband’s three daughters. Her father later had two more children, a boy and a girl, with Magda.

Mummy's two sisters were named Irene and Alice. I never heard much about Alice. But I later met Irene when I was in my 40s.

While Mummy’s oldest sister Irene took the pragmatic path of trying to get along herself with their father's new wife, my mother refused to compromise. She daydreamed she would be adopted, like how Little Orphan Annie was adopted by Daddy Warbucks and loved by all who knew her in the Sunday comics. I think that desire stayed with her during her whole life, and she passed onto me the longing to be adopted by a nicer, more-loving family by osmosis.

Although Mummy and her sisters eventually had came home to live with her father and his second wife, they did not get along. How badly did they not get along? Grandpa Kaposi divorced and remarried Magda several times, and he married another woman named Margaret and divorced her too in between his first and second marriages to Magda. By all accounts, there were many screaming fights when Magda and my grandfather were together.

In the middle of all that upheaval, during the brief marriage to Margaret, Irene, met the boy she eventually married. Oliver Nadosy was her transitory step-mother’s son, and they met again later and fell in love and married. Their's was an odd variant on the story of "How I met your mother": "Well, you see, she was my step-sister when my mother was married to her father for a few years."

My mother’s rocky life at home ended when she was forced to go out and make her living on her own from the age of twelve. She cared for the children of a well-to-do family to earn room and board while she finished high school and then went to a secretarial college. The only time she saw her father after she left home at twelve would be when he took her out to dinner from time to time.

I never realized that divorce was so prevalent in my grandparents generation, until a cousin did some genealogy research and unearthed all the records of my grandfather’s marriages. I don’t know whether I can trust all the details I learned second hand, but as I recall my cousin told me that each time Grandpa Kaposi got married, he built a new house, and both times he and Magda divorced, she got the house. Reminds me of the joke that nine-times-married Zsa Zsa Gabor—who come to think of it was another Hungarian— told Johnny Carson on the Late Show. “I’m a good housekeeper, dahling. Every time I get divorced I keep the house.”

In spite of the fact that my grandfather had invited my mother to come to LA so he could help her out, soon after she moved there to join him, my grandfather moved to Rialto in San Bernadino county to a farm he bought to live with Catherine, his fourth wife, and so my grandfather had left my mother not for the first time, this time on her own in Los Angeles county.

What made it easier for her was that the war years were pretty exciting for young people, and there were many new opportunities for women to make a living since most of the men were away at war.

After my dad was discharged from the hospital and deployed to northern California, my parents married in San Francisco in a quick wartime ceremony in the rectory of the Old Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception, near Chinatown.

They had a double wedding with my dad’s sister Agnes and her sailor fiancé from Arkansas named Raymond Corder.

We always called my red-headed Aunt Agnes, Peggy. She’d gotten the name when she was taking care of her sister Mary’s little boy, Richard Faye during the early years of the war. Dickie couldn’t pronounce Agnes, so he called her Peggy, and she went by both names for the rest of her life. Uncle Ray sometimes called her Aggie.

To meet up with Ray for the wedding, eighteen-year-old Peggy took a train by herself cross country from Boston, where they’d met, to Vallejo, California, where Ray was stationed. Several times over the years, Aunt Peggy told me she told everyone she was on her way to “Valley Joe.”

She liked to tell stories about herself that made her look dumb, although she was actually a smart woman. Sometimes she acted both dumb and bratty, I think because it amused men, made them think she was even more appealing than she already was. She came by the bratty attitude naturally by being the petted late arrival in the family, born about twelve years after my father, who was her closest sibling in age, and she was a favorite of her red headed father, Frederick.

When she met my Uncle Ray, he was on leave from the Navy in Boston. They met in a bar too, in an area called Scollay Square where a notorious burlesque house had been located in the previous generation. During the war, Scollay Square had begun to cater to military men on leave. Peggy had gone out that night with a free-spirited Irish aunt who was separated from her husband. Uncle Ray bragged later that he’d pretended to be interested in the “old woman,” to get closer to the cute young one. Peggy was only sixteen or seventeen at the time. Curvy Peggy was dying her hair blond in those days, and Uncle Raymond said the night he met her, he thought she was the prettiest thing he had ever seen.

During the war, Aunt Peggy had joined the ranks of women working for the war effort. She became a skilled welder in the Boston Navy Yards. She got a taste for working outside of the home that never left her. She didn’t want to be a housewife and was uninterested in homemaking. My uncle used to try to get her goat by saying that if he’d do it all over again, he’d marry someone who could cook. But she knew better.

Photos taken in the afternoon after the morning wedding at a long-since-closed photography studio on Market Street show my mother and my aunt wearing fashionable summer suits and hats, high heels and nylons, with big orchid corsages pinned to their suit lapels. Aunt Peggy’s suit has a fur cuff, and my mother is wearing a hat and holding a pair of gloves. My father looks solemn and stiff in his brown army uniform and hat, and my equally tall, dark-haired Uncle Raymond flashes his white teeth in a broad smile in his sailor’s tanned face, cocky in his navy blues, with his white sailor cap tilted in a rakish angle. For some reason, the background of the photo is sloppy, cluttered with an unrecognizable object on the right.

Many years later, one of the things my uncle told me was that between the wedding and the photo session, he and my dad had gone out drinking and left the “girls” in the hotel alone together. I wonder what amount of hurt at that unromantic escapade of her newly-wedded husband was hidden behind my mother’s bright smile, in the photos that afternoon. I suspect my father looked stiff because he was trying to keep himself together after the post-wedding celebration at the bar.

The war threw together young people from all over the country whose parents came from all walks of life and all kinds of educational, religious, and financial backgrounds. They were typical for their times.

Everyone was wearing a kind of costume, so differences in backgrounds weren’t noticeable when couples would first meet. The men were attractive in uniform. The women were glamorous in another sort of uniform, with the latest hair styles and the most fashionable clothing styles that they could afford, which were greatly influenced by their favorite movie stars. Many, many, marriages resulted from chance wartime encounters between young people. Most of them were far away from their homes. When the war was over, the young couples usually went back to live near one or another of their families of origin and tried to make a go of it with their new spouses, in spite of sometimes radically different expectations on how to live.

As World War II came to an end, the four couples came back to stay at my father's parents' apartment at 40 Symphony Road in Boston for a while, until they were able to figure out what would be the next steps in their lives.

Grandma and Grandpa Sullivan lived in a seven room second floor apartment that had been carved out of a three story brownstone home. Symphony Road was in formerly genteel area of the city, a five minute walk from Symphony Hall, but the neighborhood was déclassé by that time. The relative poverty of the street was evidenced by how both the upstairs and downstairs neighbors were Irish widows who lived alone, and I remember my family talking about “the Negroes” who lived in other apartments on the block. Later, in the 1960s, the area was zoned for redevelopment, then the tone of the neighborhood became upscale again, and the apartments are now condos priced way out of the reach of people like us.

My father’s mother Rose was a homemaker, and his father Fred was a tool and die maker, a talented one, Uncle Ray later told me. All four of their children, Mary, Rose, Joseph, and Agnes, married during the war years. Remarkably, none of them divorced. All four of the couples worked through whatever problems they had, the marriages endured, and only death came between them.

My mother was the first to arrive at my grandparents’ apartment, in August, a month before the war in the Pacific ended. She had left San Francisco when Daddy was transferred to Orlando, Florida. By then she was quite pregnant with me.

Mummy always told us that during the long train ride across the country she kept singing “Sentimental Journey,” a song that was a big hit for Doris Day and Les Brown and his Orchestra in 1945.

Going to take a sentimental journey, a sentimental journey home . . ..

She was dreaming that she would find the loving family that she had always longed for at the end of her journey.

Her sentimental dreams on the train dissolved after she got to Boston. My father’s Irish family was supportive and loving to immediate family members and regarded outsiders with suspicion and criticism, and with big dollops of paranoia and unforgiveness for real and imagined slights thrown in.

Uncle Ray and Aunt Peggy arrived at the 40 Symphony Road apartment about a month after my mother arrived. After the wedding, Uncle Ray had gotten a month's leave, starting on August 15. Agnes and Ray first went to Illinois where Ray's mother Teeny and his sister Ruby were working in a war plant. Ruby waited for her husband to get discharged, and then they all went for a visit to Raymond’s home town in Arkansas.

City-raised Aunt Peggy hated the way Ray’s relatives lived. “They had outhouses!” was all she would say about what she didn’t like about life in Arkansas, while she wrinkled up her nose.

Peggy and Ray arrived in Boston in September when Ray was supposed to report again for duty. By the time Ray and Peggy got to Symphony Road, Mummy was already planning to join Daddy in Orlando. Their arrival spurred her departure. Peggy and Ray saw her off on another train, Florida bound.

After a jolting Jeep ride at the Orlando Army Air Force base jump-started my mother into premature labor, I was born on October 3, 1945, weighing five and a half pounds, a month and a day after the war had ended on VJ day. I was born ahead of the curve of the baby boom, which started nine months after the war ended with a huge explosion in the birthrate in 1946.

I was born at a hospital on an Army Air Corps base in Orlando, Florida. My mother told me that when she cried out during labor, the surly nurse told you, “You’ve had your fun, now you’ve got to pay for it.” The only other thing I remember my mother saying about her time in Orlando is that they had huge flying cockroaches there.

My father was discharged from the service a few days after I was born. Sometime before Christmas my father and mother moved with two-month-old-baby me back to Boston.

Daddy had briefly tried to find a job in Florida, but the wages were too low. The three of us were back in Boston by Christmas, so I must have left Orlando when I was two months old. I've often idly wondered how it has happened that even though I’ve traveled through most of the states since then, I've never been back to Florida again.

For a time all four of Fred and Rose Sullivan’s children and two grandchildren were crowded into the apartment on 40 Symphony Road. Aunt Rose’s husband, Austin Scott, (whose nickname was Billy) had just got out of the Army, and Aunt Mary’s husband, Earl Faye, had just gotten out of the Navy. So, with Billy and Rose and Earl and Mary at 40 Symphony Road, that added up to a total of ten adults, plus three year old Dickie Faye, and baby me.

Every room in the seven room apartment except the kitchen and bathroom was turned into a makeshift bedroom, including the front room with the bay window that they called the parlor, and the dining room. The dining set was moved into the kitchen, and everyone crowded in and ate meals there. The kitchen was actually two rooms. The dining table squeezed into the bigger room, and a stove and icebox were in the smaller room, which was a kind of cook-in pantry.

That's about when, according to Aunt Peggy, Grandma Sullivan came down with shingles. In case you don’t know, shingles is an excruciatingly painful viral disease related to chicken pox. It attacks the nerves, and it is often precipitated by stress. I can well imagine there must have been a toxic amount of stress with all those strong personalities cooking, eating, sleeping, washing clothes, some honeymooning, some caring for a new baby, and some fighting, all squeezed in together.

Eventually two of my dad’s sisters moved away from Massachusetts with their husbands, but my aunt and uncle stayed living with my grandparents, and my dad and mother and I stayed nearby in Boston.

My father returned to his former job on the railroad after he got home, and he started looking for a better paying job.

There was a shortage of housing for returning veterans and their families. But in Dorchester township, a group of barracks called Camp McKay was empty. Camp McKay had been built on land formerly called the Calf Pasture. It consisted of mud flats isolated on the edge of Boston Harbor on Dorchester Bay, with a dump, a landfill, and a sewage plant where Boston’s sewage was dumped into the harbor at high tide to be washed out to sea. There was no public transportation, no amenities either, such as libraries or food stores. It’s hard to imagine how the people coped who lived there.

The camp had housed Italian prisoners of war and those who were guarding them during World War II. In 1946, when the prisoners of war were moved out, Camp McKay was converted into the Columbia Village Veteran’s Housing Project. One book that described the history of that part of Boston said, “A mile to the north, across from the long arc of Carson Beach, lay South Boston, the working-class Irish Catholic enclave, and beyond it downtown Boston. A mile to the west lay the established three-decker neighborhoods of Dorchester. But her, for acres all around them, was nothing but marsh. . . .”

As soon as they could get one of the units, my parents moved into Columbia Village.

My father and my uncle could have qualified for the GI Bill and gone to college. But it seemed too long a time to wait before they could be able to make a living. Raymond took a shorter course for barber training, and he worked as a barber the rest of his life.

I think of my uncle’s persistence in his job and his marriage as a kind of heroism. I say that because Uncle Ray had been a gambler in the years he’d spent at sea, and he was used to easy money, and easy women. He lied to join the Navy before he was 18. His own father had left him and his mother and sister, so he in many ways he was raised by the worldly tough sailors he’d lived among for about a decade. And during those days by fair or foul means, I don’t know for sure, he was a gambler. He had odds-beating good luck, and was always flush with spending money. The fact that he gave up the thrill of easy money and loose living to get up in the grey dawn every weekday morning to take a bus to the barber shop in gritty downtown-Boston and return home twelve hours after he left, and that he faithfully supported his family after the profligacy of his early youth, well those things make him remarkable in my eyes.

Daddy took the civil service tests for the typical Irish working man’s jobs in Boston, policeman and fireman. He passed both exams. He didn’t accept the first offer he got to work as a policeman because my mother didn’t want him to carry a gun. She would later tell us that she didn’t want him to be in danger, and we would all silently agree it was sadly ironic, considering what happened to him after he took what she thought would be a “safer job” with the Boston Fire Department.

In the summer of 1947, my father got hired as a fireman at the Ladder Company 19 firehouse in South Boston, only two and a half miles away from Columbia Village. My sister Martha was born eleven months after me, my “Irish twin”—which in case you don’t know is a slang term for a child born less than a year after a previous sibling.

Aunt Peggy and Uncle Raymond had a daughter a month before Martha was born, and Ray overcame Peggy’s family’s objections and named her Marybelle.

By December 1947, my dad had been on the job for less than six months, and he still was classified as a provisional firefighter, when he got killed in a firetruck accident.

Fourteen months after Martha’s birth, my mother was eight months pregnant with another child that was due the next month.

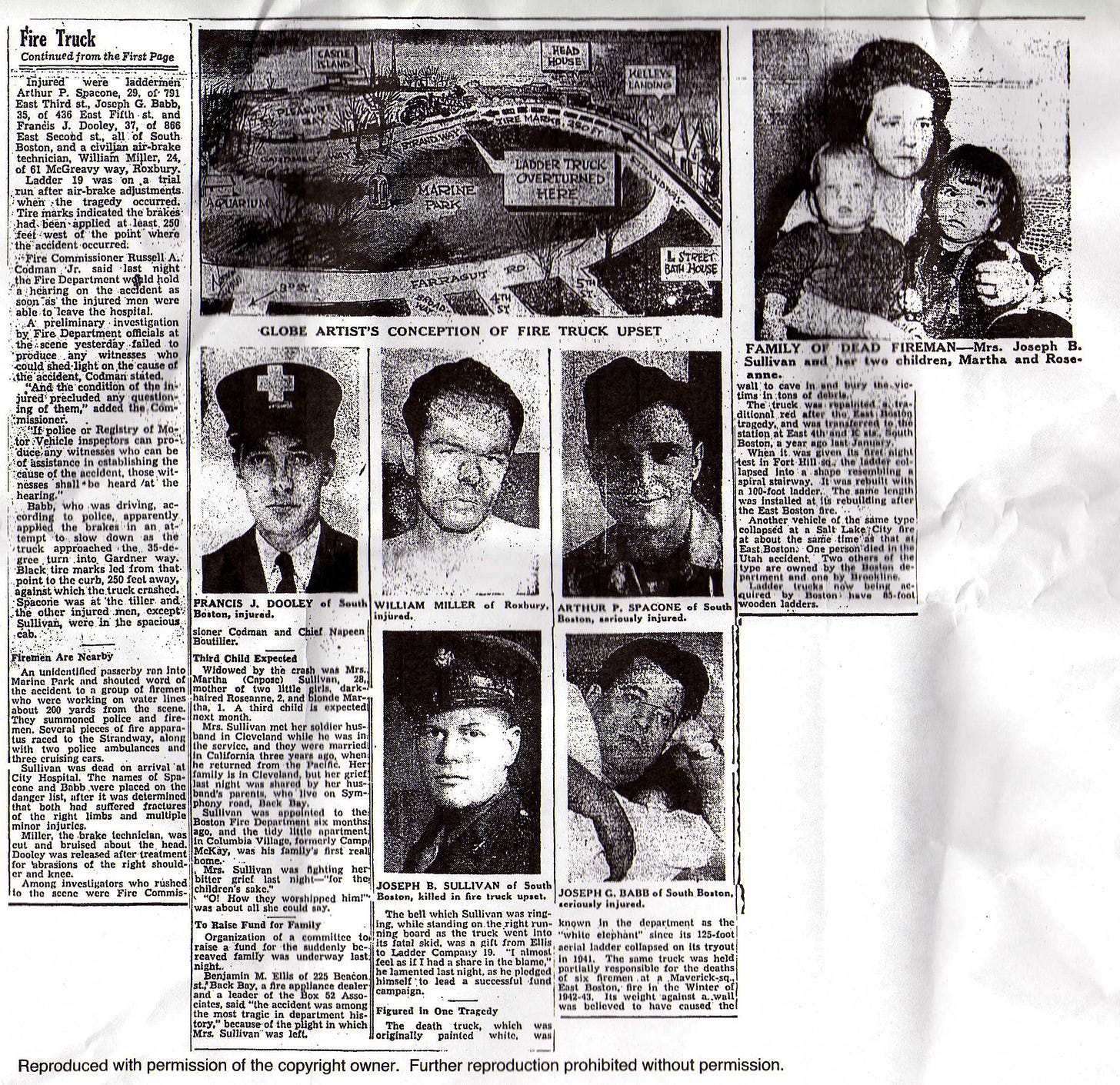

On December 3, 1947, the captain of the firehouse had the sad duty of coming to our home to tell my mother that my father had been riding outside at the back of one of the ladders on a fire truck when it tipped and rolled over in a freak accident. The accident had happened just a few miles away from where we were living on Columbia Point. It was my grandparents’ thirty-seventh wedding anniversary.

So my mother was left with two-year-old, me, one-year-old, Martha, and she was pregnant with my sister Joe-anne, who was born January 15, 1948, the following month.

Back in September of 1941 when the city bought it and put it into service, the firetruck my dad had been riding when he died had been painted white. In later years no one was quite sure why that color was used. The truck earned the nickname the White Elephant because of its color and because of a series of malfunctions with its ladder and its brakes. It had the largest ladder ever on a firetruck. First the extension ladder jammed during a drill. This was the start of the jinx. After the ladder was repaired by the manufacturer, a far worse failure occurred. During a three alarm fire in East Boston on November of 1942, the ladder collapsed. Six firemen died, and many others were injured.

After the ladder was repaired again and shortened, the truck was eventually assigned to the Ladder 19 firehouse where my dad worked. The White Elephant nickname stuck even after the truck was repainted red. Many firemen were afraid of it, and some refused to ride it. It jack-knifed several times and had persistent brake problems.

On the day my father died, while a representative of the brake company was on board after the most recent round of repairs, and they were testing the brakes, the truck overturned as it navigated a U turn around City Point and crushed my dad to death.

I still have newspaper clippings about the wreck. A photographer snapped a photo of my devastated mother sitting holding my blonde sister Martha, and dark-eyed, dark-haired me.

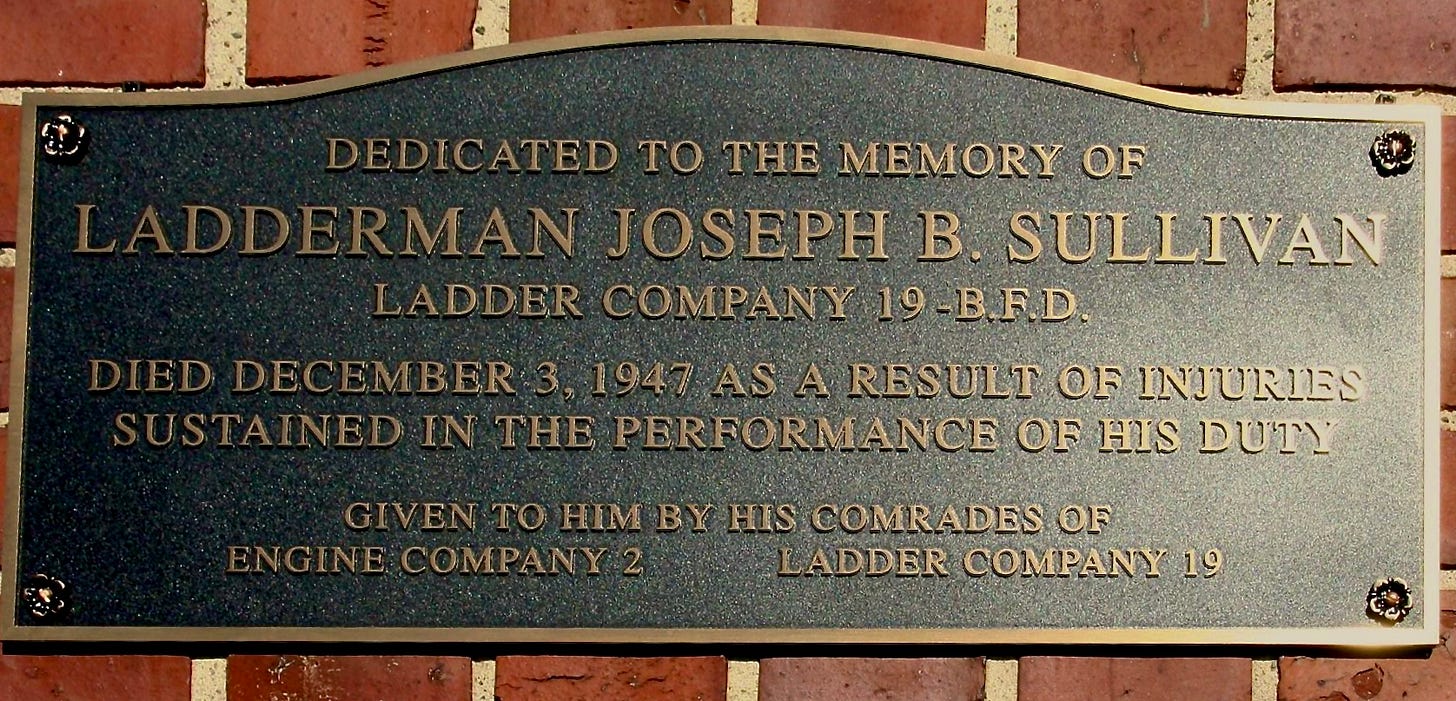

More than fifty years later, I attended a ceremony during which a plaque was installed commemorating my father at the Ladder 19 firehouse.

I found myself sitting next to a former Boston Fire commissioner, Paul Christian, who had come there to give a brief talk as part of the ceremony. He told me he was a very young child living nearby in Dorchester when the accident happened. I was very moved that was his first memory in his life, when he was 3 years old. His family heard the noise of the crash, the sirens, and the commotion. He later emailed me photos of the crash and copies of the newspaper reports.

My youngest sister, Joe-anne, was born the month after my father died, on January 15, 1948. My mother called her Joe-anne Bernadette after my dad, Joe for Joseph and Bernadette for his middle name, Bernard.

She used to tell us that Joe-anne and Daddy had met in passing, when Daddy was going up to heaven and Joe-anne was coming down. She also repeated that he had gone to confession the Saturday before he died, which was one source of comfort for her and the rest of the family.

Grown-ups in my father’s family never explained what was going on to us kids. I only have vague memories of standing with my middle sister and my cousin at the door of a downstairs neighbor lady’s apartment on what was probably the day of Daddy’s funeral, and watching the adults all dressed in black filing down the stairs from our family’s second floor apartment and out the front door. Aunt Peggy and my mother were quarreling. Nobody would tell us where they were going.

And nobody told us where my mother went either when my mother disappeared several times during my childhood, for years at a time. But that's a whole other story.

This linked memoir piece is about some of the other things that happened to my mother, myself, and my two sisters after my father died.

From email:

Oh my goodness Roseanne, the voices that make it on to the leadership and influence stage have not half the content, character and clarity of yours.

In Christ,

[JA]

From email:

I am so sorry to hear that.

My dad was a Truck Captain with the San Jose Fire Department and I'm a retired Fire and Arson Investigator with the Santa Clara Fire Dept. (And, I had the sad duty of investigating the death of a firefighter.)

May God bless all those who serve, have served and their families. [Deacon CA]